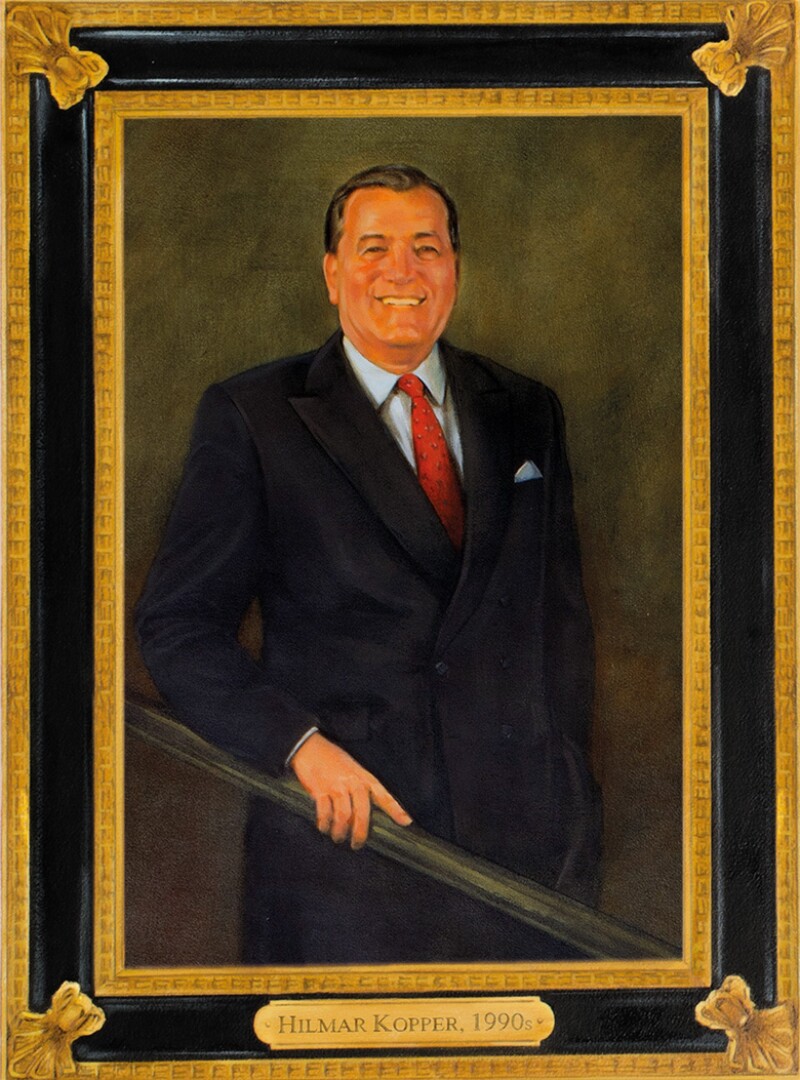

Hilmar Kopper ran the bank that every other firm feared in the 1990s. He transformed Deutsche Bank from a conservative domestic business into a leading global financial institution. Just how far Deutsche has fallen today shows how far it rose under Kopper.

IN ADDITION |

|

For 30 years Deutsche Bank has fascinated people perhaps more than any other financial institution. Today, as the latest management group struggles to define a plausible business plan, the fascination is like rubber-necking at a car crash. There is an almost morbid interest in a once-great bank now laid so low.

But a great bank it was – and not that long ago. Deutsche was the bank of the 1990s. It was the one everyone else watched; it was the one almost all other banks feared. In his eight years in charge, Hilmar Kopper brought about a stunning transformation that gave Deutsche the platform to compete at a global level.

The irony is that the transformation Kopper led was forced upon him by many of the same challenges that Christian Sewing – the sixth person (including co-heads) to succeed Kopper since he moved to the chairman’s role in 1997 – is struggling so hard to meet today.

For example, as Kopper said in a landmark interview with Euromoney’s then chairman and editor-in-chief Padraic Fallon in 1994: “In Germany, good advice from your bank is free.”

That and a domestic banking system that Kopper said made Deutsche “the biggest bank in the world with the smallest market share” forced the rationale for his expansion plans away from home. Then, as now, Deutsche’s management was faced with the same stark choice: become more profitable in Germany or do something somewhere else.

It is ironic that, for this interview in 2019, Euromoney met Kopper at arguably Deutsche’s lowest ebb – as politicians tried to broker a merger between the bank and its main competitor, Commerzbank. Kopper described the potential tie-up as “ridiculous”, a view validated by the rapid unravelling of the discussions.

Today Kopper is a remarkably sprightly man in his mid 80s: sharp-minded, despite the occasional apology for forgetfulness, with a charm and bearing redolent of a bygone era of Europe’s elite.

|

| Hilmar Kopper |

His personal story – from wartime refugee to arguably the most important German businessman at the time of the country’s reunification – mirrors that of Europe itself. He talks with emotion of the difficulty of the early years for him and his family.

He recounts tales from his career with pride and a real sense of enjoyment that is hard to draw out of bankers today. But his frustration and disappointment about the current state of the bank he ran is clear – tinged, perhaps, with a sense of what he might have done differently.

Nevertheless, Deutsche nearly mastered the platform that Kopper built. By 2007 it was the biggest bank in the world, with total assets of €2 trillion and a now unimaginable return on equity of 18%. In 1990, Kopper’s first full year in charge, what was until then a conservatively run commercial bank just starting to dabble in London-based capital markets, was a fraction of the size, with a balance sheet of €312 billion, much of it rooted in strategic shareholdings in many of Germany’s leading industrial companies.

Today, the bank labours under a bloated and complex balance sheet, and returns 0.4% on equity. Its strategy – which veers from more of the same to potential mergers with local competitors – is uneven at best and nonexistent at worst. What remains is cost cutting and consolidation – although both face political and labour obstacles – and a handful of businesses, such as cash management and foreign exchange, that still have global heft.

Turbulence

The turbulence of German events was never far away, both for the bank and for Kopper. He became Vorstandssprecher (spokesman of the board) of Deutsche in 1989, following the assassination of Alfred Herrhausen by left-wing terrorists at 9am on November 30. The board members rushed immediately to Frankfurt, and Kopper was elected that afternoon in a 30-minute meeting. Respectfully, no announcement was made.

“Deutsche at its best,” Kopper was later to tell Euromoney.

The Berlin Wall had fallen 21 days before and Germany was reunited 11 months later. Deutsche itself had achieved a similar feat already in 1957, in the west at least, when Hermann Abs finished reconstructing an institution dismembered into 10 parts by the Allies after World War II.

I belong to a generation, after the war, which suffered terrible hunger. My God, you wouldn’t know how many potatoes I stole from farms. And I feel shame talking about it

Abs and the bank had not had a blameless war, although punishment for those sins was quickly subordinated to the economic expediencies of the Cold War.

Kopper had risen through the ranks of Deutsche with the energy and determination of a migrant. Born near Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) in 1935, he joined the westward migration of 12 million Germans displaced and expelled by the Soviet Union and the reconstituted countries of eastern Europe. Settling with his family near Cologne, Kopper was guided by a cash-strapped father into an apprenticeship at a nearby branch of Deutsche.

|

Kopper and his family were among the millions of German refugees fleeing Danzig as Russians advanced at the end of World War II. |

Kopper repeatedly jumped on opportunities as they emerged, including a formative stint at Schroders in New York and a period running Deutsche Asiatische Bank, both of which fostered his enthusiasm for the world beyond Germany. At each turn he took an interest in the processes, mechanisms and technology that could boost efficiency. By 1969 he was running the most profitable branch in the network, in Leverkusen. By 1977 he was on the board.

Herrhausen had begun Deutsche’s push into London and the capital markets in the mid 1980s – and also immediately into the cultural wrangles that have bedevilled the bank ever since.

As Euromoney reported at the time, an early star of Deutsche Bank Capital Markets, Karl Miesel, described by colleagues as a prima donna, flounced out in a huff at the overbearing micro-management of the commercial bankers in Frankfurt.

DBCM management meetings featured squabbles about the wallpaper and the carpets. An intractable quarrel about whether Stanley Ross, a high-profile and respected markets banker appointed as an executive director, merited a car parking space like the managing directors, was sent to the Frankfurt board for resolution.

Herrhausen pressed on. Deutsche bought banks and brokers in Canada, Austria, Australia and Italy. At the time of his death, negotiations to acquire Morgan Grenfell in London for what was regarded as a full price of £950 million were reaching their conclusion. This was the beginning of a concerted push under Kopper into investment banking and the birth of a parallel and ultimately supreme ‘Anglo-Saxon’ expression of Deutsche Bank.

In January 1990, Euromoney wrote: “Deutsche could just become the bank of the 1990s.”

And so it turned out. The bank’s return on equity inched from low single digits towards 12.5% by 1999. Awarding it ‘The world’s best bank’ in 2000, Euromoney said that it had “emerged as the most powerful sales, trading, and new-issue firm in European bond markets after a careful build-up of a large institutional distribution network to complement its strong banking ties to corporate issuers.”

It looked like the dream business model for a wholesale universal bank. The infamous ‘flow monster’ was born.

One of the key moments in the bank’s journey to becoming a global player came in 1995, when Deutsche Morgan Grenfell secured Edson Mitchell from Merrill Lynch to be its global head of markets.

Mitchell in turn poached former colleagues, including Anshu Jain, who later became co-chief executive. Fellow future chief executive Josef Ackermann joined from derivatives specialist Credit Suisse Financial Products in 1996. Mitchell himself was an arch-trader. People still recall his willingness to bet on anything, especially against younger colleagues. A cult of personality emerged. His untimely death in December 2000 is often cited as the beginning of Deutsche’s current problems, although a strategy that can fall with one man is not a robust one.

|

| Kopper with Josef Ackermann |

Controversial

Kopper moved to the supervisory board in 1997, replaced as Vorstandssprecher by Rolf Breuer, who, unlike Kopper, was a trader by background. In 1999 Breuer oversaw the $10 billion acquisition of Bankers Trust, a controversial transaction that seems only to have had Kopper’s lukewarm endorsement. It brought a much-coveted US footprint but took Deutsche further into the world of derivatives and structured products. Less well known – and praised – is the fact that Bankers Trust also turned Deutsche into a world-class transaction services bank.

The seeds may have been sown then for today’s balance sheet problems and strategic headaches; however, a formidable achievement for the time remains. Within 10 years a respected and feared global player had been built from a stolid and parochial German commercial bank. Inevitably, there was still no unitary culture and Kopper today regrets that the bank lost “a commonality of purpose” along the way.

The bank didn’t entirely neglect the domestic side of the German banking conundrum. A merger with Dresdner Bank was briefly explored in 2000. Deutsche had made a concerted foray from 1995 into online banking with Bank 24.

This could have paved the way for a reduction in the cost of the branch network and a push into consumer banking elsewhere in Europe, but an ill-advised programme in 1999 to herd poorer clients into Bank 24 stymied the initiative.

Today, it still struggles to incorporate Postbank, a post-crisis acquisition designed to shore up its deposit-based funding and reweight its business towards the domestic market.

John Orchard and Clive Horwood met Kopper in late March, first in a building a short walk from Deutsche’s Frankfurt HQ with a whole floor dedicated to a generation of retired Deutsche chiefs, complete with loyal and attentive PAs; and then over lunch in a bürgerliche bistro around the corner, where, among others, another former Deutsche chief executive came to the table to pay his respects.

In the interview Kopper discusses his storied career, shares his views on the state of German banking today, rails against a system of political interference that he clearly believes is not fit for purpose in the modern age, and reveals a hitherto unknown – and eventually unsuccessful – plan for Deutsche to kick off a cross-border consolidation in Europe.

He won’t be drawn on where the fault lies for Deutsche’s current problems. A gentleman banker to his core, he refuses to criticize his successors. After four hours of discussions, Euromoney leaves with a strong feeling that Deutsche could really do with a banker of Kopper’s dedication, experience and sense of stewardship today.

Euromoney Many of your old colleagues on the board have an office on this floor of this building.

Hilmar Kopper (HK) We are the older generation. None of the newer generations will have this. One day we will be extinct!

Euromoney The board meetings at Deutsche Bank were always very formal. How do you interact with each other today?

HK It has loosened a bit. But I have to admit that, for no good reason… I can’t really explain it… I’m still on second-name terms with all of them; which is a bit silly.

Euromoney Do you sit down together and reminisce on the old times?

HK We try to have lunch together once a month.

Euromoney What do you talk about?

HK Well, the bank, of course. Recent developments; how we see it. We are all outsiders. None of us has an inside line. If we did, we wouldn’t talk about it. So, we sit there and we try to be elderly, wise men, but there is no proper outcome of our discussions.

Euromoney You discuss the current situation and the possible merger with Commerzbank?

HK Basically, we all have the same feeling. I think all of us rather strongly feel ‘why the hell do we need a merger?’ We think it’s nonsense. Particularly Mr Schulz’s [Social Democrat leader Martin Schulz] argument that German industry would need a German champion to assist them abroad. What should be Commerzbank’s contribution to that?

The three pillars is traumatic. Taking this as a symbol of the stability of the German banking landscape is ridiculous. It can only be invented by someone who has no idea about banking. The government is running this business

Euromoney You don’t see any positives?

HK This is ridiculous. In all other fields, they overlap. They are retailing, we are retailing. We are about twice their size already. We both like the medium-sized German clientele, which I think Deutsche Bank has unfortunately somewhat neglected. Nobody can tell you what happened to Dresdner Bank. It was the number three bank in Germany for many years. They have just disappeared and nobody misses them, which is a clear indication that we obviously have too many banks. Or had too many, I don’t know.

Euromoney Is the real problem the three pillars system [private-sector, public-sector and cooperative banks] in German banking?

HK The three pillars is traumatic. Taking this as a symbol of the stability of the German banking landscape is ridiculous. It can only be invented by someone who has no idea about banking. The government is running this business.

Euromoney You don’t think the three pillars would partially be solved by consolidating the private pillar more?

HK But the private pillar almost doesn’t exist anymore. There are these two names and the rest is gone.

Euromoney Do you think that the job of running a profitable private-sector bank in Germany remains as hard as ever?

HK Yes. This is partly to do with the central bank’s interest policy, which is awful, particularly if you have loads and loads of very cheap deposits that you cannot make use of.

Euromoney But doesn’t it run deeper than that? Essentially, people in this country don’t like the idea of money begetting money.

HK Yes. It’s interesting we’re talking about this around the time of the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth. Not so much has changed in the thinking of many Germans.

Euromoney What is the process by which Deutsche can become a strong bank again?

HK It will only come slowly. We have to continue to cut our costs. I think we have made some progress, but it’s not enough. More should be made, can be made. I’m very positive on that because I think Sewing [Deutsche chief executive Christian Sewing] is good at it. Sewing is a person who stands by his word.

Euromoney How well do you know him?

HK I have met him. He was very open.

Euromoney Does he come to seek your advice?

HK That’s neither expected nor practised in Deutsche Bank. But there are opportunities to exchange our views.

Euromoney Something has to happen to the balance sheet though. The bank has a huge balance sheet for one with such a small market cap.

HK It’s a long process. A lot of these are long-dated assets. That’s the problem.

Euromoney Unless they sell those assets to somebody else.

HK But then you have to sell some of the assets below book. I imagine that’s the worst thing for a business person that you can do, having to sell things below book.

Euromoney Does Germany need a national banking champion?

HK Yes, but I cannot see why merging with Commerzbank contributes towards that goal. Deutsche is already a G-Sib [global systemically important bank], certainly in terms of the size of its balance sheet. It’s just its performance is not that of a G-Sib. Balance sheet total in comparison to equity, that’s not a proportion that we would like to live with for too long. Something has to be done.

Euromoney Before the start of its current difficulties, was Deutsche generally a well-run bank?

HK Most of the time it was. Of course, I often ask myself what changed and why and when and how? What always pops up in my mind is that we started to make mistakes when we were no longer run as a German bank, when we started to become more Anglo-Saxon minded.

Euromoney What does a German bank mean, in that sense?

HK Strict oversight. Responsibility. It was a culture in which you had to be responsible for what you do.

We built up in London, but the most important was the United States. To grow there, we had to do it the Anglo-Saxon way; otherwise we wouldn’t have had success. But we probably gave up too much of what had made us strong in the first place

Euromoney How much was the role of the Vorstand, the collective responsibility, and the fact that the head was known as a ‘speaker’ rather than a chief executive, part of this?

HK That was tradition and I was sorry when they threw it away. I thought it was a sign of distinction because the speaker was not decided by the supervisory board but by his colleagues on the executive board. It was a show of independence, to say we decide who is our leader. Your position is stronger when you are appointed by your colleagues rather than by an outsider. But the executive board had become a problem: we were equals, but that meant each member could think they had full control of their own sphere of influence. We lost that commonality of purpose.

Euromoney But do you think it would have been possible to keep that old culture, the German culture, as Deutsche became more international?

HK No. We also have to acknowledge that things around us changed. We built up in London, but the most important was the United States. To grow there, we had to do it the Anglo-Saxon way; otherwise we wouldn’t have had success. But we probably gave up too much of what had made us strong in the first place.

Euromoney The loss of collective responsibility when you stopped being a German-style bank?

HK Yes. But there were other factors too. A big one was the tragic death of Edson Mitchell. It was a huge blow to the bank. Although he was American, he was a real leader who took real responsibility.

Euromoney Could you have done more to grow in Europe?

HK When I stepped down as speaker to join the supervisory board, at my last meeting I gave my colleagues a sort of testament. I said: In retail, we should only be in Germany and very selectively in a few European countries with consistently higher-margin retail businesses. Global retail banking is very difficult. If we wanted to expand further, we should do it by developing direct banking. This is why we founded Bank 24. I even invented this name because I suddenly realized that this name is universal. You can use it in every language, you don’t have to translate.

Euromoney But it did not work out that way.

HK No. The idea was fouled up. We opened Bank 24 in Germany and the idea was we offer clients a choice between those who wanted our services electronically and those who wanted to use the branches. Instead, we automatically put all our smaller clients into Bank 24 and retained all our best clients in Deutsche Bank. This caused an uproar. It was the biggest communication mistake you could make. The typical Deutsche Bank mistake. We told our clients what to do, instead of letting them make their choice.

Euromoney Twenty years ago this was an idea ahead of its time.

HK And it was a complete failure. Bank 24 had to disappear. Because it failed so miserably in Germany, it never took off at the European level. I thought that we could take it to France, use it in some other places. No. And now look at the success ING Direct has had in Germany since.

Euromoney But it’s hard for banks to make money in German banking.

HK Yes, and it’s not just competition from the state sector. Recently a German court made a ruling about how much money banks can make from individual current accounts. What is the business of the German court to decide on that?

Euromoney Isn’t it because the attitude in Germany among the political class is that money has to get into the economy however cheaply we can get it and that banking isn’t a legitimate way to earn a living?

HK They don’t see banks as bringing money into the economy. They see banks as providing a necessary service to humanity. And the individual is entitled to have it free of charge. This is the basic belief deeply embedded in German politics.

We opened Bank 24 in Germany and the idea was we offer clients a choice between those who wanted our services electronically and those who wanted to use the branches. Instead, we automatically put all our smaller clients into Bank 24 and retained all our best clients in Deutsche Bank. This caused an uproar. It was the biggest communication mistake you could make. The typical Deutsche Bank mistake

Euromoney If that weren’t true, do you think that Deutsche would have concentrated more on its home market?

HK Yes, much more. We eventually tried something different, acquiring Postbank. It was the right step, to counter this ever-increasing internationalization. It gave us a bigger client base, increased it to about 20 million. That was much better than the 10 million or 12 million that we had before. I was fully behind it.

Euromoney People still criticize that deal. Do you think it was a good thing to do?

HK I couldn’t say so now because of the way it’s been handled. We thought we’d be able to use all the deposits for financing, but we could not. That was an internal mistake.

Euromoney The acquisition of Bankers Trust is also viewed by many as a mistake, with hindsight.

HK I think it injected some genes that we really needed at that time. Because we shouldn’t forget: why did we do it? Because we weren’t relevant in global investment banking without a strong US presence. Bankers Trust had recently bought Alex Brown, which was a jewel. The problem was [that] Bankers Trust turned out to only be a small investment bank and was rather a big trading house.

Euromoney It seems remarkable that a smart group of bankers did not really know what they were buying.

HK Today it’s the truth, but this is with hindsight. I would not have bought Bankers Trust. The idea would not have occurred to me. My successor, Rolf Breuer, was a trader. So he had a different view. Edson also thought we needed to be more involved in this business to become better aware of the flow of money. It was an argument which at that time impressed me. But I was out by then. I was not involved in the decision making.

|

| Kopper with his successor as Vorstandssprecher, Rolf Breuer |

Euromoney This was the birth of the Deutsche flow monster. For almost 20 years, it was the best in the business. But it was also the start of many of the problems in the wholesale bank, especially the culture of financial engineering.

HK That went totally out of control. Not only in volumes but also in all sorts of derivatives, as we all know.

Euromoney The bank grew too fast without the right controls?

HK Maybe. Many other people are much more knowledgeable on some of these issues than I am. I was never much of a trader. I know that, even in my time as chief executive, at almost every executive meeting, we talked about the ever-increasing balance sheet size brought about by the ever-increasing volume of derivatives. And eventually we were too big. We became a major source of insecurity for the rest of the world, the banking industry.

Euromoney You were concerned about this in the 1990s?

HK We started to be concerned. The ever-increasing balance sheet was nothing we were proud of.

Euromoney No one took responsibility for the situation?

HK This crosses my mind quite often. Why didn’t you sit down with a group of people and go through that book? Knowledgeable people. Just to see and form your own picture, is there something to this too big, too long, too complex? The question I have is how did they value and book it for the last 10 years? Why did no one know, or why didn’t it occur to anyone that [it] could become a huge source of almost certain loss?

This self-definition of risk and value is dangerous. That is where our assessments, our values and our balance sheets must have been wrong for 10 years. Scary.

Euromoney Do you think Germany’s political class does enough to support its banks?

HK I’ll give you one example. After the financial crisis, a lot of banks were forced to pay big fines in the US. Deutsche Bank was initially expected to pay around $14 billion, it settled for around $7 billion. Half the amount. Look at some other European banks. They were sued for similar amounts but only ended up paying $2 billion to $3 billion. Far less. And that’s because their politicians and central banks lobbied on their behalf with the US authorities.

In Germany, politicians and the central bank prided themselves on not interfering. And they were happy that Deutsche Bank was being punished. These are the same people who now talk about needing a national banking champion. It is ridiculous!

Euromoney In the article we published 25 years ago, you said Deutsche was the biggest bank in the world with the smallest domestic market share. Isn’t that fundamentally the problem that you, your predecessors and all your successors have had to deal with?

HK This has been our constant concern.

Euromoney Is there an answer?

HK Cooperative banks are merging all the time, all over the country. But there are still far too many. The problem of course is that government is too heavily involved. Every community has a savings bank, every region has a bank and the head of the supervisory board is a politician. They are deeply involved in everything to do with the bank. And their purpose is investment, not making a return. If you read my local paper, if they publish a report on a cooperative bank, they never use the word profit. It doesn’t exist. It is irrelevant.

Euromoney You’re not particularly optimistic that the politicians will address this issue.

HK No. I see no turnaround in the thinking.

I think we’ve been very well off with Merkel. She is not a typical leader in the sense that she’s never made a good speech in her life. But she has been a good leader. Sometimes I think she is too stubborn and single-minded. But she has been the uniting force in Europe

Euromoney Even though some politicians have pushed for a national champion through the merger of Deutsche and Commerzbank?

HK Then you have another crowd who says you’ve created another problem – a bank which is too big to fail. This is why I think the national champion idea is rubbish. If Deutsche Bank disappeared, most of its business would not go to other German banks. They’re much too small, they’re not connected. It would go to foreign banks. Look how big and powerful the US banks are today.

Euromoney Could European banking union be a counterweight to this?

HK I don’t mind European banking union, if the correct foundations are laid. But they are not there at the moment. Right now everyone tries to parade European banking union on the shoulders of someone else. I think the reply of the French banks on the invitation to become active in Germany speaks for itself.

Euromoney What do you think of the political class in Germany today?

HK It is not first class. Good solid workers. Some of them I would even call reliable. I think we’ve been very well off with [Chancellor Angela] Merkel. She is not a typical leader in the sense that she’s never made a good speech in her life. But she has been a good leader. Sometimes I think she is too stubborn and single-minded. But she has been the uniting force in Europe.

Euromoney During your time in charge Deutsche sold down its shareholdings in some of Germany’s biggest industrial companies. Did the bank, or those companies, lose something in the process?

HK It provided protection against unwanted foreign influence. But I was a big believer that the system had served its purpose. It was a leftover from the post-war years, never intended to be something that lasted for ever. And I think many of the companies have performed better since they lost that protection and are properly exposed to market forces. For the bank, it meant we could no longer rely on hidden reserves.

Euromoney There is a fascination with Deutsche that predates the current problems.

HK Yes, true. Part of this is the bank’s name. The other day I came across the speech I had to make on our 125th anniversary in Frankfurt. And this is where I talked about the name and what it always implied for the bank.

Euromoney It’s always been in part a political job, one that makes you a public figure?

HK You saw it during the financial crisis when Josef Ackermann was in constant political demand during all this period.

Euromoney He was perhaps the most prominent banker at the time in terms of leading the industry’s response to the crisis.

HK Absolutely. I’m fully with you. I feel very close to Joe. Still, today. I don’t blame him for many things that he’s been blamed for in our media. His intentions were good. He is unfairly treated, particularly in this country.

Euromoney Do any particular deals stand out during your time as chief executive?

HK Oh yes, the Pirelli bid for Continental in the early 1990s. Pirelli already had some shares and they wanted to buy the rest. We at Deutsche Bank felt that we should protect Conti. Normally my colleague Ulrich Weiss, who spoke fluent Italian, would have dealt with this. But I took the reins because we had to speak to Enrico Cuccia, the head of Mediobanca, who was advising Pirelli and had also built his own stake in Conti.

I feel very close to Joe Ackermann. Still, today. I don’t blame him for many things that he’s been blamed for in our media. His intentions were good. He is unfairly treated, particularly in this country

Euromoney Cuccia was a legend of European banking. How was he to deal with?

HK He received me in Milan and we had a deadly serious discussion. It was not easy. I told him the attempted takeover – to try to get round rules on German voting rights – would not work. I told him: ‘I think I know Germany better than you do. My advice is let it go and I’ll help you. You will be reimbursed.’ And I knew this would happen, because the day before I had talked to Gerhard Schröder, who was the prime minister of Lower-Saxony [and later German Chancellor] and said: ‘Mr Schröder, your Lower Saxony government will have to throw in half of the money.’ He said that I should not worry and he kept his word. Like that, the deal was over. Pirelli fumed. Cuccia had his money. And I was happy.

Euromoney Why was the deal so important to you?

HK Firstly, this was the first transaction where officially Morgan Grenfell was the adviser, not Deutsche Bank. John Craven was the point man on the deal. And Alfred Herrhausen [Kopper’s predecessor as speaker], until his death, was a nonexecutive chairman of Continental. So I thought we had to protect our image and show that we are able to protect the company. And we succeeded. And we used that to improve our investment banking business in Germany. We said: ‘Look at what the British investment bankers can do.’

Euromoney One of the big shareholders in Deutsche was Allianz. But you were also competitors in banking and in insurance. How did that work?

HK I always tried to have them on our board as shareholders. Henning Schulte-Noelle, the head of Allianz, was on our supervisory board. I wanted it for a simple reason: to prove that we had nothing to hide. I wanted to build the second-largest German insurance group. I succeeded.

Euromoney Why?

|

Henning Schulte-Noelle, Allianz |

HK Not because I wanted Deutsche Bank to be involved in the insurance business. I wanted a significant German insurance group in order to trade that with Axa for their big stake in one of the big French banks, Société Générale.

Euromoney So you weren’t particularly ambitious about the idea of bank assurance, which was fashionable then?

HK It was a bit of a game of billiards. That was a wonderful cover. They thought we were also looking at big bancassurance, ‘the business of tomorrow’, which Allianz went into by buying Dresdner.

Euromoney That didn’t work out so well.

HK Even getting rid of it didn’t work!

Euromoney But you had said at the time – even in the Euromoney interview in 1994 – that you weren’t interested in French retail.

HK I didn’t want to have to build something up myself. But if I could have got Axa’s 35% stake and then increased it beyond 50%, it could have worked with a bank of that size.

Euromoney So this was your vision of creating a truly European champion bank?

HK This was no vision. This was a very simple picture – the only way to get a German bank into a highly protective French market. And the lure was it would have allowed a French insurance company to gain a real foothold in Germany. But then my friends here lost their nerves and deserted me. So the whole thing collapsed.

Euromoney When you left as speaker, you became head of the supervisory board. That’s a transition that would probably not happen for governance reasons today.

HK I always thought that the pinnacle of what you can do for a public company was to select a new CEO from outside. If they come from within, you know them. You’ve been to meetings with them. You’ve been in difficult situations with them. It’s much harder to know you are picking the right person if they are new to the company.

Henning Schulte-Noelle, the head of Allianz, was on our supervisory board for a simple reason: to prove that we had nothing to hide. I wanted a significant German insurance group in order to trade that with Axa for their big stake in one of the big French banks, Société Générale. It was a bit of a game of billiards. But then my friends here lost their nerves and deserted me. So the whole thing collapsed

Euromoney You had no role in choosing Breuer as your successor?

HK He was my colleague for many years. But I did not choose him.

Euromoney No one talked to you about whom your successor should be?

HK Some came and asked me what they should do. I declined to give an answer. But I did say: ‘Whatever you do, I will accept it. There is no doubt.’

Euromoney Your own succession was rather different.

HK Yes. In my case, there was no changeover. We met in the early afternoon after my predecessor was murdered in the morning. So there was not much choice.

Euromoney Herrhausen was seen as a visionary who fundamentally changed Deutsche.

HK He was a visionary, that’s true. But a lot of people in the bank thought he was not a banker because he had come from a corporate industrial background. To my mind, he had been in the bank for seven years before he became speaker; that was enough to pick up what he needed. He was an extremely smart intellectual.

Euromoney Did you keep the same mission when you took over?

HK Mostly. I changed the tempo and some of the direction. He wanted to change the bank from the inside by giving it a new structure. He overstretched in terms of keeping the goodwill of the top 30 people in the bank. He thought they were too slow to follow him. But they were not too slow. They slowed the process down because they didn’t like the direction he was taking the bank.

Euromoney How did Herrhausen react to that?

HK He was frustrated by it. And he made the mistake a few weeks before he was murdered of confiding to someone that he would rather become chief executive of Daimler than stay at Deutsche Bank.

Euromoney He wanted to leave?

HK He is said to have said that. I have no clue. But I wouldn’t rule out that he said something like this. And this, of course, did not meet with the approval of many people in the bank. They thought that their hero was deserting them. And he was a hero to many. That was his nature. He was a born leader.

Euromoney So you might have become speaker anyway?

HK A week before it happened, I was happy to be in a position to build up the investment bank, following the Morgan Grenfell acquisition, under Herrhausen’s protection – because he was a big help to me most of the time. But I was not set mentally to dedicate my whole life to the bank, which you have to do if you want to lead the bank.

Euromoney Your own life story is a remarkable one, something which in some ways mirrors the history of Europe over the past nine decades. You lived in Danzig (Gdansk), in what is now Poland, for the first 10 years of your life, many during World War II. When did you come to the West?

HK We came west in January 1945 as the Russians were approaching: my mother, my two sisters and my elder brother. We tried first to come out with two horse-drawn carriages. My father couldn’t join us; he had to stay with the army. We got about 20 miles. There were so many refugees. It was chaos. Plus military moving both ways, some fleeing, some coming to support. So my mother decided to come back. The next morning, there was a little bus, which had been amended to the wartime situation. It ran on wood rather than gasoline. We eventually made it to the western side – then the whole bus broke apart.

Euromoney It must have been traumatic.

HK I learnt a lot from that experience. My elder brother and I felt that we had to look after the family. Also my mother was not very experienced. She didn’t know how to cook an egg; she always had lots of staff. We were scared to death that we would starve because of my mother’s inexperience.

Euromoney Did she learn?

HK Very fast. It’s like with birds. When the young birds are hungry and make a lot of noise, mothers seem to learn what to do. We laughed for decades after that about some things that happened. But then after a year, my father appeared.

Euromoney He had been in a prisoner of war camp?

HK The German troops he was with had retreated to a small peninsula, which they managed to defend against the Russians until Armistice Day.

The day before, May 7, the commander in charge offered my father a place on the last fishing boat they had, which took about 10 people, because he knew he had four children. They wanted to go north to reach Sweden. They never reached Sweden.

After eight days, they came on the shore and someone appeared with a gun and said, in a strong English accent: ‘Hands up boys.’ Six months later he was released from the POW camp because he knew about agriculture. My parents had agreed that they would try to make it if possible to a place south of Hamburg, where we had friends living. So my father knew that and he walked all the way. Took him about a week or so. And he found us.

Euromoney Do you think that experience made you a tougher person than you would otherwise have been?

HK Yes. We had to maintain the family. My brother and I, we were very experienced black-market dealers. Particularly in used ammunition. But we were particularly good at trout fishing. And we sold the trout to the British canteen. There was a local officers’ mess and we traded it in for Senior Service cigarettes. With cigarettes, you could get almost anything. It was the best currency.

On my third day, some guy was congratulated by the manager of the branch for his 25th anniversary at Deutsche. The manager gave a little speech. It was horrible. This guy had achieved nothing. It was so awful that I came home and I said to my mother: ‘I’m not going again: if that happened to me after 25 years, I’d rather shoot myself

Euromoney Why did you go into banking?

HK Very simple. When I finished school in Germany, I wanted to go to university and study physics or architecture. But my father could not afford for two of us to be at university and my elder brother was already studying. My father suggested banking. So I said: ‘What bank?’ My father said: ‘Of course Deutsche Bank’ because they were the bankers to the company he worked for, where he was finance director. I started on April 1, 1954 as an apprentice for two years, after which I was taken on as a full employee.

Euromoney What did you learn?

HK There were only about 60 employees in that branch. So I saw how everything works. I saw the money coming in and the money going out. And the cheques coming in and what happens to cheques.

Euromoney Were there any lessons you took with you through your career?

HK The most important thing I learned was, if someone asks you to do something, just say yes. That gives you a wonderful opportunity to escape dull work.

Euromoney What was the working environment like?

HK On my third day, some guy was congratulated by the manager of the branch for his 25th anniversary at Deutsche. The manager gave a little speech. It was horrible. This guy had achieved nothing. It was so awful that I came home and I said to my mother: ‘I’m not going again: if that happened to me after 25 years, I’d rather shoot myself.’

Euromoney How did your mother persuade you to go back?

HK She said: ‘Come on, things will change. You can always go to university.’ So I applied and told the bank that probably in about three months I would leave.

I received a phone call from the then head office, which was Düsseldorf. And I was asked to come to Düsseldorf for an interview. They told me they were thinking of sending me to either Belgium or London as a trainee. But eventually they offered me an exchange job working for Schroders in New York.

Euromoney Why Schroders?

HK It was a correspondent bank to Deutsche. There had not been a German trainee there since the war. It was a wonderful opportunity and I liked the idea that it was a small, private bank. That kept me in the bank. When I left, they gave me a letter – which they had to send as part of the exchange deal – saying I had been of no material value to the bank. I still have that letter.

Euromoney They’d obviously already spotted some talent in you.

HK I built up a bit of a reputation for not keeping my mouth shut, let me put it that way. I didn’t yell at anyone, but when I thought I should say something because it could be done better, I said so. It was a very formative experience. Germany since the war had been taking its first steps back to democracy but in America, this was like a new life from heaven.

I went to baseball games; saw the New York Yankees of Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra. You could go to the wonderful old opera house for $3.60. With a friend, whose father was a partner in Schroders, I rented an apartment on 96th Street near the park. Deutsche sent me money every month and if I covered for someone who went on leave, they paid me 50% of that person’s salary. I never told Deutsche. They would have deducted it!

Euromoney How did banking on Wall Street differ from banking in Germany in those days?

HK Their way of processing transactions was far ahead of what we had in Germany. They were willing to spend money on machines. If a machine cost DM100 at Deutsche Bank, you had to beg for two months to get it. They were doing things we barely did at all, like trading foreign exchange. And I learned about credit analysis – the famous American spreadsheet.

Euromoney Were you sad to leave?

HK It was a very special experience. Of course there were a lot of Jewish people in the bank and they understandably eyed the young German with some suspicion. But the bank looked after me wonderfully.

Towards the end of my time, Schroders encouraged me to go and see other parts of America. They suggested I go to the west coast, but I did not have the money for it. They financed some of the big Hollywood film studios and had co-financed an early TV series, and arranged for me to go and check the books. I took the Greyhound bus all the way there. One night I was invited for dinner. The host was Spencer Tracey. I almost died!

|

Peter Wallenberg, SEB |

Euromoney Was it a comedown to return to Germany after that?

HK No, it was a very exciting time at Deutsche Bank. Towards the end of my time in the US, Hermann Abs had reunited Deutsche Bank. Remember, since the war the bank had been broken up geographically. It was of course Abs’s vision to recreate a big national bank in what was left of Germany.

Euromoney Before you became the speaker, what was your most enjoyable job at the bank?

HK By 1971, I was manager of the most cost-effective branch in the Deutsche Bank network. Our cost-to-income ratio was 36%. I had a wonderful team, and our advantage was we had some big clients, notably Bayer and Agfa. We’d brought in some technology that wasn’t being used elsewhere in Deutsche Bank. Then head office found out and asked me to give presentations on how we used technology.

Euromoney How old were you at the time?

HK Thirty six. And then I was invited to become the head of Deutsche Asiatische Bank, which was based in Hamburg. I barely had any idea where Asia was on the map.

That began a wonderful adventure. We merged it with other partner banks and created European Asian Bank. I travelled constantly. I opened branches from Pakistan to Korea. In the Philippines, I had to personally persuade president [Ferdinand] Marcos to give us a branch licence.

Euromoney Was this a starting point for Deutsche’s internationalization?

HK It was a tradition already. Deutsche Bank’s second branch office ever was in Yokohama. We had 112 branches in China before World War I. When the consortium that owned European Asian Bank broke up eventually and Deutsche took over control, one of the partner banks wanted our licence in Singapore in return for their stake.

Deutsche Bank didn’t want to give it to them. And I said: ‘Yes, give it to them.’ The next morning I went to the monetary authority in Singapore and applied for a new licence, which six weeks later I had.

Peter Wallenberg at SEB said: ‘We Scandinavians, we know how to run a retail operation.’ So they bought BFD. Two years later they had to close it. They had no idea how to run the bank because you cannot run a retail operation in Germany in the same way you do in Sweden, or indeed elsewhere

Euromoney You seem to move quickly when you see an opportunity.

HK Yes, I hated people who spent too long thinking about things. It suggested they were not on top of the situation. You should know what to do in the next three seconds when the opportunity arises. Although, I must admit, sometimes this led me to make some mistakes.

Euromoney Such as?

HK The temptation to go into banking in Poland. I was pushing this and I should have known better. Remember I was a Polish citizen for the early years of my life.

Euromoney You think the decision was based on sentimentality for where you were born?

HK At that time I was not aware of it but, looking back, proper analysis tells me that I was a bit carried away.

Euromoney Sentiment and human error will, of course, always be part of banking.

HK Yes. When BFD, the German unions’ bank, was in trouble my good friend Peter Wallenberg at SEB in Sweden made an offer for it. I went to Stockholm and I said: ‘Peter, I think you should not buy it. Why, for heaven’s sake, should you be able to run a German retail operation? Even we at Deutsche Bank have said we do not want to own this bank.’

He said: ‘We Scandinavians, we know how to run a retail operation.’ So they bought it. Two years later they had to close it. They had no idea how to run the bank because you cannot run a retail operation in Germany in the same way you do in Sweden, or indeed elsewhere.

Kopper on compensation

“Money does not mean much to me”

Deutsche Bank in the 2000s became synonymous with high levels of compensation. Hilmar Kopper was perhaps responsible – but had a very different attitude to his personal remuneration

Euromoney Executive pay has become a big issue in the banking industry. Do you think bankers today are overpaid?

HK In my first five years at the bank I constantly felt I was underpaid. I went to see my boss and complained bitterly. It didn’t impress him very much.

Euromoney Even when you were speaker, you were never awarded stock or cash bonuses. That was only 20 years ago and yet it seems a lifetime away.

HK No. That was never done then. But the whole new system for the top people and pay was arranged by me when I was nonexecutive chairman. It was my duty to look after them. We were trailing the rest of the crowd and we were losing good people, or we didn’t have access to good people.

Euromoney But you never got to benefit from that yourself?

HK No, I was out by then. Very fortunate for me, really.

Euromoney Fortunate because?

HK I thought I had enough. On the old Deutsche Bank board, every member received exactly the same remuneration. It was about a €1 million in the end. To be honest, I have a very poor relationship with money.

Euromoney What do you mean?

HK Money does not mean much to me. I belong to a generation, after the war, which suffered terrible hunger. My God, you wouldn’t know how many potatoes I stole from farms. And I feel shame talking about it. When you are hungry, you do things. There are things in life that are more important. Now this, of course, is only true with my own money. It is not true for a banker with other people’s money. As a banker, it is your prime responsibility to look after that. If you do it well, you are successful.

Euromoney And what makes people unsuccessful?

HK There are always two things I hate in life: laziness and stupidity. And the worst is a combination of both.

Kopper on connections

“No one would dare leave”

As head of Deutsche, Kopper made connections at the highest level. One led to a memorable invitation.

|

Euromoney As head of Deutsche Bank, you were one of the most influential bankers or even businessmen in the world. Did that open up interesting doors for you?

HK Yes. David Rockefeller, former head of Chase Manhattan, asked me to be treasurer of the Bilderberg group, which I did for 15 years. David was the co-founder of course. There weren’t that many of us involved in those days – maybe about eight to 10 people got together each time to discuss the issues of the day.

Euromoney It’s often mentioned in the press these days as a shadowy organization pulling the levers of global power.

HK As a conspiratorial, secret society? It was nothing of the sort. One of my first meetings was when the Germans had agreed to host the event in Baden-Baden in 1990. As host you had special duties to perform. One of them was to have dinner with Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands. Her father was the founder of the group of course – the first meeting was held at the Bilderberg Hotel. She was the hostess, so you sat with her and these dinners went on for many hours as she loved to talk. Three o’clock in the morning. And no one would dare leave.

Euromoney It sounds like you enjoyed the conversation.

HK Oh, yes. I held her in very high esteem. After a few years of meeting at the Bilderberg, she had built up some trust in me. One day my telephone rang, she said: ‘Mr Kopper, I need your help.’ I said: ‘What can I do for you, your Royal Highness?’ She said that her son was deeply in love with an Argentine girl and she happens to work for a bank in New York. I said: ‘Yes, I’ve heard so.’

She said: ‘Can you bring her somewhat closer to Holland, but not into Holland?’ So we made her deputy delegate of Deutsche Bank in our Brussels office. Now she is queen consort of the Netherlands.

Euromoney Did you go to the royal wedding?

HK Yes. And I got a kiss from the bride!