Illustration: Vince McIndoe

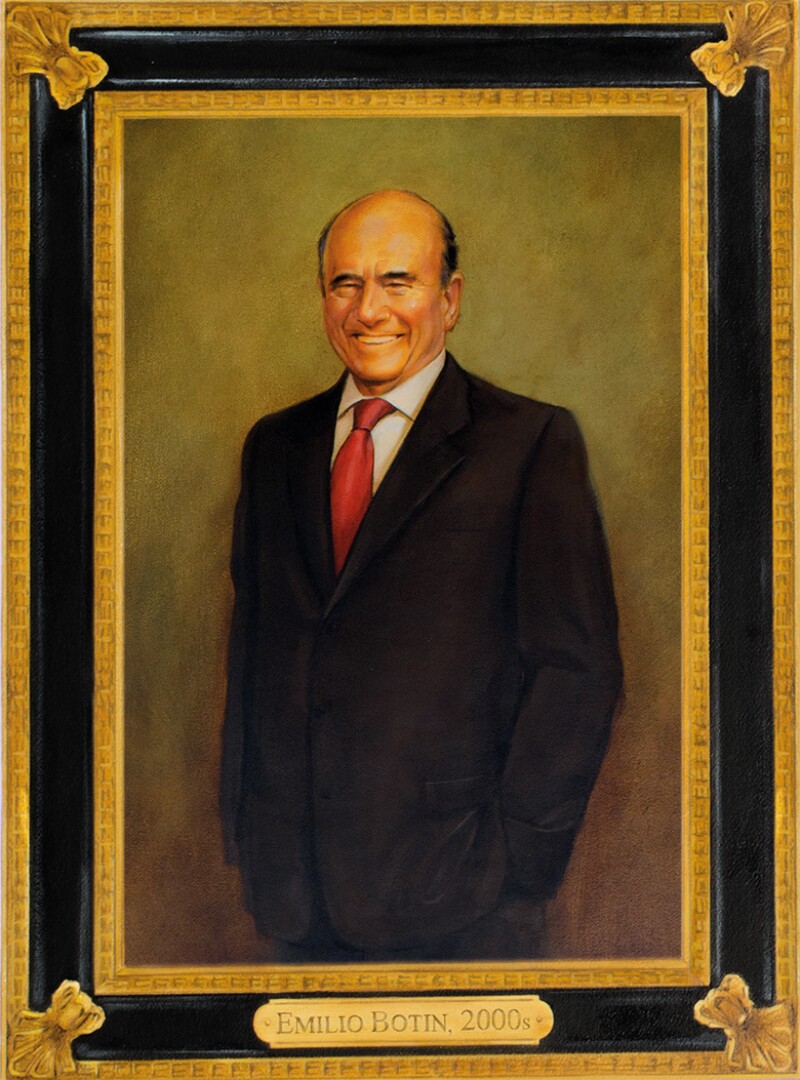

Realizing early on that banking was a business where scale mattered and diversification was essential, Emilio Botín turned a regional family firm from southern Europe into an unlikely new force in global banking. He was a master of the merger and trod a path that no other European bank has followed. But the pace of growth left challenges for the generation that followed.

|

|

IN ADDITION |

|

Emilio Botín’s speech to the 2008 Euromoney awards dinner, where Santander was named best global bank, has gone down in banking folklore. Botín revelled as a commercial lender from northern Spain picking up the biggest prize in banking in front of the big investment banking-dominated institutions of bigger and richer countries, especially UK and the US.

The win was largely thanks to Santander having steered clear of the structured credit investments that were pushing other banks towards the abyss. Alluding to a poem by colonial-era British poet Rudyard Kipling, the late executive chairman declared: “If you don’t fully understand an instrument, don’t buy it. If you would not buy a specific product for yourself, don’t try to sell it. If you do not know your customers very well, don’t lend them any money. If you do these three things, you will be a better banker, my son.”

As a belated piece of advice for the 2000s, this was spot on. But the tongue-in-cheek literary reference reflected a traditionalism and even paternalism that was a part of his management of Banco Santander. He was the third Botín to run the bank. His daughter Ana is the fourth and, perhaps, the last.

Nevertheless, Emilio Botín’s career went hand-in-hand with globalization, European integration and financial liberalization in Spain and Latin America. In the decade after the introduction of the euro, Santander went from a domestic to a global player. So far, this transition has proved much more durable than that of other banks that tried to do the same. And in 2008, there was still as yet little obvious sign of complacency at the top of the bank as a result of its deal-making success.

Santander could have gone the way of any number of now-forgotten mid-tier lenders in Europe: swept away by bigger rivals or dwindling to insignificance and bankruptcy. The fact that it did not was in part because of the connection to its heritage, but also, crucially, thanks to Botín’s early recognition that second-tier banks would struggle to survive.

|

|

THE BANKERS |

|

The bank was predisposed to benefit from the resurgence of globalization in the late 20th century. It had branches in Latin America before it had them in Madrid, as one of Botín’s senior lieutenants once pointed out to Euromoney. When the Botín family founded the bank in the northern Spanish city in the mid 19th century, Santander was the biggest port city for trade with Latin America, especially Cuba, then still a Spanish colony.

Barely two decades after Botín took over from his father (also Emilio) in 1986 at the age of 52, Santander went from a minnow to one of the top 10 banks worldwide by market capitalization.

In 1986, it was not in the world’s top 100 banks by that measure, nor among the big three banks in Spain.

That year, Spain’s biggest lender was Banco Hispano Americano (later Central Hispano) and Banesto was the country’s biggest bank by profit.

Fifteen years later Santander had absorbed both banks to become the biggest bank in Spain. It went on to buy Abbey National, a top 10 UK lender, and Banco Real, a top five private bank in Brazil, alongside a series of smaller acquisitions from Poland to the US.

Old-fashioned as it seems, family stewardship may have given the former chairman the freedom to undertake a series of daring acquisitions that would make Santander fit to compete internationally, and not just in Latin America. The largest cross-border bank merger in Europe ever at the time, the Abbey purchase remains arguably the most successful deal of its kind.

Antithesis of arrogance

The Botín family had the paintings, the palaces and the country estates of aristocracy. Spain’s King Juan Carlos even made Botín’s wife, Paloma, a marchioness for her musical patronage. But there was another side to Botín that perhaps not everyone saw.

|

Emilío Botín would visit Santander’s branches incognito, joining the queues of customers to get a sense of how the bank was working. “He was always on top of all the numbers: he was like a hawk, watching everything from above,” says one banker who knew him well. |

“Emilio was always humble,” says Andrea Orcel, the former president of UBS and a big-time adviser to Santander before the bank’s abortive decision to appoint him CEO last year.

“While undoubtedly powerful, he was the antithesis of arrogance. He always sought challenge and the advice and guidance of people he trusted. He always demonstrated his appreciation: as an example, whenever we had worked with him, he would take the time to send hand-written notes of thanks to me, my team and my bosses. Imagine how powerful and busy he was, and yet he still took time to say thanks like this. It’s no wonder he inspired such loyalty and that people like me were so keen to work for him.”

Botín, according to those who worked closely with him, combined a broad vision with sometimes surprising attention to detail. This could be useful – such as visiting Abbey National’s branches incognito before buying the bank – and it could be quirky, like noticing the shadow cast by the trees at the new Botín Foundation arts centre in the city of Santander in the 2010s.

“He was always on top of all the numbers: he was like a hawk, watching everything from above,” says one banker.

That hawk’s eye view extended to every operation of the group. Once a month, Botín would famously take himself off around Santander’s branches unannounced, joining customer queues and getting a sense for himself of how the bank was working from the ground up.

Business trips were intense. One colleague recalls a three-day visit to Mexico. On the flight over from Madrid, Botín consumed all the information he needed. Every minute of the day was accounted for with meetings, from senior management to junior staff. The colleague describes the meetings as “intense, detailed and personal”. And by this time Botín was already into his mid 70s.

António Horta-Osório, chief executive of Lloyd’s Banking Group and a former chief executive of Santander UK, marvels at Botín’s “astonishing ability to keep the focus on the strategy, but also to come down to earth and make sure that the details are taken care of.”

This needed long hours and a lot of energy. Big protein-filled breakfasts, unusual for a Spaniard, provided the fuel: topped up by Coca-Cola later in the day.

“All his energy, time and passion: everything was the bank, the bank, the bank,” says Alfredo Sáenz, Santander’s second in command, and chief executive for a decade until 2013.

Ana Botín, today’s executive chairman, agrees: “He lived for the bank. The bank was his life.”

Spanish bank chairmen have a habit of staying in their jobs into old age. Former executive chairman of BBVA Francisco González only stepped down at the end of 2018, aged 75, after almost 20 years at the top. Isidro Fainé retired in 2016 at a similar age and after a similar period leading CaixaBank. Botín was, however, the only one of the three to remain executive chairman until his death, aged 79, in 2014.

Perhaps the best comparison with Botín is neither Spanish nor a banker, but the former head of Cemex, Lorenzo Zambrano. He too turned his peripheral family concern into an unlikely global multinational. Zambrano died the same year as Botín, aged 70, also of a heart attack, after making his father’s company on the outskirts of Monterrey in Mexico one of the world’s biggest cement companies. Like Botín, this was achieved through a bold acquisition strategy.

Unchallenged overlord

Botín’s acquisitions created the international retail and commercial group that is Banco Santander today. There were, however, limits to how far he was prepared to expand the bank. His belief was that Santander should be active in no more than 10 markets and that it should aim for a minimum market share of 10% in each of them, to give it some pricing power. Limiting the number of markets stopped the bank becoming over-complex – one of the key risks Botín wanted to avoid.

Yet perhaps the most important thing to recognize is that he was a winner in a banking industry that has disappeared since 2008. He got away with making high bids for some banks – arguably too high in Brazil and the UK, for example – because of his charisma and his position as the bank’s unchallenged overlord.

A Botín may still be at the top of Santander, but the post-2008 world is very different. It would be far more difficult to get such big and risky deals past the regulators and international institutional investors today.

In Ana’s words: “Looking back, you could argue that we overpaid on a couple of occasions. But Santander would not be what it is today without the businesses he built.”

Her stewardship of Santander’s global payments business, on the other hand, is a sign of the need for new priorities in a new era, especially in today’s digitized economy.

“Timing is everything in business; what was not true then is true now,” she says.

The contrast between Botín and his successor is also shown in their respective interests. Emilio, among other pastimes such as Formula 1, was known for elephant hunting. Ana, although she shares the family love of golf, populates her Twitter feed with discussions of yoga and speciality teas.

|

Ana Botín, today’s executive chairman, says: “Emilio lived for the bank. The bank was his life” |

What has not changed – and has if anything become more necessary, especially in Europe – is the importance of size in banking. Santander has scale in Spain and global diversification because of the late chairman’s risk taking.

The best pay-back of his strategy today may be that Ana’s Santander aspires to be the third-biggest bank in the world in terms of digital spending, thanks to a €20 billion medium-term programme.

The continued parochialism of the family and the bank can come as a surprise. The bank and the family are connected to the city of Santander by more than just name. Emilio was born in the city in 1934; he made sure his children were born there too. Under him, the family charitable foundation commissioned an €80 million community and arts centre there, designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano, which opened in 2017. On Emilio’s death, Ana’s brother Javier took over the running of the foundation – and the chairmanship of the local golf club, Real Golf De Pedreña.

Ana has demonstrated a similar dedication to her birthplace with the announcement last year of a €40 million project to transform the bank’s former Cantabrian headquarters into a cultural centre to house its art collection.

Across Spain and beyond, there have been clear benefits to Santander and BBVA’s creation of “a different model of international bank” – one with a large domestic commercial banking market share that provides stable funding for standalone local subsidiaries.

“The model has demonstrated its strengths,” says José María Roldán, head of the Spanish banking association, who was head of bank regulation at the Bank of Spain throughout the first decade of this century. “It was created to protect Spain from the turbulence of Latin America and it has protected Latin America from the turbulence of the eurozone.”

Santander is no longer the kind of investor proxy for Latin America that it was 20 years ago. Emerging markets account for roughly half its profits.

Botín’s mergers and acquisitions mean that more of its assets are now in Spain and Europe. Its international businesses also helped make it a bulwark of the Spanish system when the regional savings banks proved less capable of managing the eurozone crisis and the accompanying real estate slump.

Although Botín expanded his bank internationally, he remained a proud Spaniard at heart. When Spain ran into banking difficulties after the global financial crisis, he refused to pull back from the country and instead committed to lending more to the economy, even if pure business logic dictated against it.

As one colleague who worked with him at the time says: “He always took the view that a bank was part of the bigger community. Sometimes you got back more than you gave; but there were times where you had to give more than you were likely to get back.”

The misconception of Emilio is that he liked to take risks. But he was very conservative. He never took risks on lending, never over-extended the bank’s balance sheet - Confidante

In 2012 – and claiming a third global best bank award from Euromoney – Botín said: “I have never in my life seen Spain in such a difficult moment as this. We’re trying to do as much as we can for the country. The situation in the country worries me, but the situation of the bank does not.”

Few deny that a heavier governance structure would have made it harder for Botín to carry out such a daring acquisition strategy during his long tenure at Santander.

“There was a combination of vision and a personal capacity to operate,” says Matías Inciarte, former vice-chairman and now chairman of Santander Universidades. Another source outside the bank says Botín would listen to everyone – and then decide on his own.

The Botín family’s holdings in the bank have dropped from 15% in the late 1990s to less than 1% today. Moreover, since his death, the family charitable foundation – which still gets its annual budget from the bank’s share dividends but now only owns about 0.5% – is headed separately, by Javier, who has the family’s voting rights on Santander’s board.

Santander still has a chief executive and an executive chairman.

However, rumours are rife in Madrid about the European Central Bank’s lack of comfort with Spain’s model of executive chairmen, after the Bank of Spain lost its sole supervisory responsibility for its banks as part of the wider regulatory reforms following the eurozone crisis.

The arrival of a new executive chairman at BBVA has sparked more gossip about how the ECB might be taking the opportunity of leadership changes at the Spanish banks to rebalance power at the top. When BBVA announced it had gained ECB approval for its choice of former chief executive, Carlos Torres Vila, to replace González late last year, it said a new organizational structure would mean Torres Vila sharing more responsibilities with the new chief executive, Onur Genç. Finance, risk, wholesale banking and country monitoring all report to Genç, who reports directly to the board.

Emilio Botín was able to use high pay as a means to buy senior bankers’ allegiance, even while effectively shutting off the prospect of them getting a shot at taking ultimate power. His top rivals and lieutenants all walked away with extraordinarily large pensions (traditionally the most generous part of bankers’ compensation in Spain).

The departures of chief executive Angel Corcóstegui in 2002 and co-chairman José María Amusátegui in 2001 from what was then Banco Santander Central Hispano were sweetened by their respective pension pots of about €108 million and €55 million. In 2013, Sáenz retired at the age of 70 with a bank pension of €88 million. The year before, Francisco Luzón, formerly head of Latin America, retired at the age of 64 with a pension of €56 million.

Today, the purse strings are held far more tightly. Earlier this year, when Santander announced that its appointment of Orcel to replace chief executive José Antonio Álvarez would not go ahead, the official explanation was that its obligation to stakeholders meant the bank could not take on the approximately €50 million in deferred pay that Orcel had racked up as head of UBS’ investment bank.

Critical mass

As regulators have helped to make investment banking less profitable this decade, Santander’s acquisitions in Spain, Europe and Latin America have all handily skewed it towards retail banking, especially in Europe.

But ultra-low interest rates are a fundamental challenge for the long-standing cornerstone of Santander’s developed market retail strategy: high-yielding current accounts. Large volumes of retail deposits have become a burden rather than an asset in Europe. At the same time, digitalization is not just an opportunity for investment but also a challenge to the legacy of Botín’s acquisitions, which were largely focused on buying up bricks-and-mortar branch networks.

One financial institutions investment banker says that, looking back, selling banking assets was the better thing to do in the mid 2000s: “It’s much easier to buy than sell. You need to be able to do both.”

Botín did do both. He could see that the consolidation going on in the Italian banking sector –with French and local lenders vying for prominence – meant that there was clear market value for Antonveneta, which was sold to Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS) in 2007 as part of the ABN Amro deal.

|

In 2008, Santander was named Euromoney’s best global bank for the second time in four years for Botín’s stunning acquisition of the best parts of ABN Amro. |

Afterwards, Botín told Euromoney he flipped the bank because MPS’s offer gave him the chance to bolster Santander’s capital ratio when the world financial situation was looking dicey. He recognized that reaching critical mass in Italy would require investment of about another €15 billion.

Inciarte also cites Botín’s negotiations with the Federal Reserve over Santander’s acquisition of a minority stake in First Fidelity, a top 10 bank in the US, in the 1990s. He made sure Santander alone wouldn’t be saddled with the bank’s capital-raising needs and later sold the stake for a large gain. Inciarte further references their work together exiting smaller Latin American countries in the 1990s.

“The misconception of Emilio is that he liked to take risks,” says another confidante. “But he was very conservative. He never took risks on lending, never over-extended the bank’s balance sheet.”

That misconception was largely based on Botín’s attitude towards acquisitions and the view that he overpaid for some of Santander’s purchases.

“Yes, he could be aggressive on price,” says one adviser who worked with him on a number of M&A deals. “But his view on acquisitions was not about buying cheap – it was about buying well.”

The Abbey acquisition was also fortunate in retrospect, as it triggered the sale of the bank’s RBS stake before that bank’s ambitions got out of hand. Three years before RBS’s nationalization, Botín told Euromoney that Santander’s shares in RBS were one of his best ever investment decisions.

“We earned 23% return on income on an annualized basis from our stake in RBS over the past 17 years,” he said, pointing to a total return to shareholders of about €4.5 billion.

Orcel, who as an investment banker at Merrill Lynch and later at UBS worked on a number of transformative M&A deals for Botín and Santander, remembers just how engaged and demanding his client was.

“Before we went to present to him, we’d prepare a 50-page document where we’d check the numbers time and time again,” he says. “Emilio would always have read the entire document in advance. Immediately, he’d hit on the three critical parts of the plan that would make or break it. He was exceptional at grasping the core of the issue at hand. And on top of that, he had an extraordinary natural instinct for the banking industry.”

Botín was also a realist. “He often told me: ‘Remember, opportunities such as acquisitions never come at the perfect time nor terms’,” says Orcel. “If they did they would be easy. So, you have to be ready to grab the opportunity if it makes sense when it comes.”

Botín did this by keeping a close, consistent eye on all the potential targets in the market.

“He knew everything he needed to know in advance,” says Orcel. “And once the opportunity came, he was never afraid to put his neck on the line if he believed it made sense, because he knew the target – and what it would bring to Santander – inside out.”

Over the last decade, Santander has inked far fewer deals with the kind of wow factor that Emilio gave them. Indeed, Santander’s much more complex position today might make his all-detail and all-vision approach next to impossible.

Banco Popular is a possible exception, but compared with some of her father’s deals one could less easily accuse the current executive chairman of overpaying. The price agreed with the Single Resolution Board for Popular, after all, was €1, although an accompanying €7 billion rights issue to help offload Popular’s bad loans puts this into perspective.

One of the advisers on the Popular deal says that it showed her father’s personality coming through in Ana. But it was also her deal, after all she had spent much of the 1990s buying banks around Latin America for Santander.

Complacency

After the 2000s, the most trenchant criticism of Emilio Botín’s record is that his deal-making success encouraged a degree of complacency.

In reality, the group needed much more than acquisitions – it also needed good management, especially of its staff. In many respects, the real work of assembling a coherent well-oiled machine from the patchwork of acquisitions in the decade before only began in the 2010s in a world of lower rates in Europe and heavier regulation.

Another banker who knew him says the former chairman, certainly towards the end of his career, fixated on some topics of interest – acquisitions and perhaps the bank’s trading positions and credit risks – and paid less attention to operational concerns such as product innovation, marketing, IT and branch networks.

Those who know her, say Ana’s attentions are broader yet more consistent, and Santander is possibly better for it now, given how large and complex the bank and banking have become.

“We had a great foundation, but there was a lot of potential to improve profitability and grow the assets we had,” Ana points out.

It changed Spanish banking and the whole competitive landscape - Ana Botín

One senior consultant who has worked closely with the firm for years says Ana is “10 times more sophisticated in management” than her father.

Her route through elite international rather than Spanish schools is more suited to managing today’s multinational group, he argues.

The most obvious change under her stewardship came the year she took over as executive chairman, when she almost immediately replaced former chief executive Javier Marín, now at the Vatican Bank, with CFO José Antonio Álvarez. Hiring Orcel might have showed similar intention to prevent any stagnation at the top of the bank had it gone through. The bank did however appoint an outsider, Ezequiel Szafir Holcman, previously at Amazon, to run Openbank, the online-only lender relaunched in Spain in 2017 as a key part of its digitalization strategy.

Ana, of course, does not hesitate to trot out her bank’s achievements to demonstrate why she is bullish on Santander: close to €8 billion in annual net profit in 2018, and rising, despite higher taxes and capital requirements, and €13 billion returned to equity and debt investors over the last three years.

Santander Brazil, under country chief executive Sergio Rial, is an especially cherished example of a core division of Santander that has seen improvements in profitability over the last five years. That is not due to a new big merger but rather to bolt-on acquisitions of card payment processor Getnet in 2014, Banco Bonsucesso Consignado (payroll loans) in the same year and the digital banking platform ContaSuper in 2016.

On the other hand, Botín is the first to acknowledge that buying Banco Real in 2007 was a fantastic deal for the bank. It is why Santander is now so well positioned in Brazil.

Getting Banco Real while selling Antonveneta is largely why Santander survived and thrived during the 2008 crisis and its aftermath in southern Europe.

|

A once-in-a-lifetime chance

|

Botín with Luqman Arnold, Abbey’s CEO, signing the deal in July 2004 |

The Abbey National purchase saw Santander decisively break onto the international stage, allowing it to win a first global best bank award from Euromoney in 2005.

The deal was: “A once-in-a-lifetime chance to join the premier league of banking,” we said. It was the first time that a foreign challenger had launched a big incursion into Europe’s most profitable banking industry.

This purchase looks fabulously successful compared with Banco Sabadell’s 2015 acquisition of TSB from Lloyds, which has been bogged down by IT problems. Whether or not Santander has fulfilled its initial promise to disrupt the UK banking industry, on the other hand, remains a matter of debate. While Abbey brought in plenty of mortgages, the basis of the Spanish bank’s strategy in the UK has been to rapidly gain market share by offering high interest rates on current accounts. Cheap current account funding traditionally underpins the profitability of UK incumbents.

The strategy was a direct copy of Santander’s exploitation of the deregulation of deposits in Spain in the 1980s via its ‘SuperCuenta’, or super account, which was introduced in 1989. Former vice-chairman Matías Inciarte remembers being elated 30 years ago at how slow bigger banks were to react to the account, which offered a double-digit rate versus the low single digits on offer in the rest of the market. Reluctant to jeopardize the fat margins they had gained from 1% current account funding, they left their share undefended against raids by Santander.

“It changed Spanish banking and the whole competitive landscape,” says Ana Botín of the SuperCuenta.

So far, Santander’s trajectory in the UK has not mirrored that in Spain, where within 15 years of the SuperCuenta’s introduction Santander had become the country’s biggest bank. In the UK it has grown from the sixth- to the fifth-largest bank, but it still has a long way to go to reach the size of any of the big four UK domestic banks. After many years, it has also retreated from trying to gain deposit share through its current account rates. Horta-Osório’s Lloyds, the country’s biggest retail bank, and Sabadell’s TSB now offer similar products to Santander’s 123 current account.

Indeed, among Santander’s core country businesses, the UK is now a marked underperformer. At 9%, its underlying return on tangible equity was two percentage points lower in the UK than Spain last year. And thanks to Brexit, the UK no longer offers the group political and economic stability relative to its other markets.

The consolidation taking place among regional banks in the US may now be a bigger opportunity for Santander than the UK, as Ana Botín focuses on turning around and developing the franchise in the northeast US.

That regional franchise, in fact, is another legacy of Emilio Botín’s leadership, due to Santander’s purchase of a majority of Sovereign Bancorp at the height of the global financial crisis in 2008. Last year, its US profitability was even lower than the UK, at 8%.

|

Knowing when to sell

|

Botín with Fred Goodwin, then chief executive of RBS |

Emilio Botín’s most astounding manoeuvres in M&A were the result of the defining bank acquisition deal of the last decade: the Royal Bank of Scotland-led consortium purchase of Dutch bank ABN Amro in 2007.

The deal still haunts European banking today. Extraordinarily, while the fallout from it was to contribute in large part to the massive state bailouts of its partners, the Spanish bank came out the better for it. It also showed that Santander could sell banks with just as much decisiveness as it acquired them.

While the whole of ABN Amro was still in play in 2007, Santander rejected all but the Brazilian and Italian parts of the Dutch group. Even before the deal closed, it had agreed the sale of the Italian part, Antonveneta, to Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena at a profit of more than €2 billion. This shored up its balance sheet ahead of the financial crisis that the wider ABN Amro deal helped to fuel.

And because Santander kept the Brazilian part, Banco Real, it became the only international bank with a top-three business in one of the big four emerging economies, which would do even more to support global growth in the years immediately after 2008.

The takeover of ABN Amro was in some respects the culmination of long-standing personal and business relationships between Santander and RBS, which served to egg on the two banks’ acquisitions. The banks took minority stakes in one another in the late 1980s, while their chief executives and chairmen sat on each other’s boards.

Botín put insights from the relationship to good use when Santander swooped on Abbey National, which triggered the end of the cross-shareholdings and board seats.

The personal relationships with RBS endured, even after 2008, as Botín himself told Euromoney: “You cannot overestimate the importance of this relationship. Each time we met, we challenged each other, shared ideas and offered our support. We learnt a lot from each other. And we were there to support each other when help was needed.”

This involved mutual support in the boardroom and in public when each bank was looking to make acquisitions. Botín said that the then RBS chairman, Lord (George) Younger, offered support when Santander wanted to buy Banesto and continued to support the management when other shareholders complained that Santander was offering too much for a troubled bank.

Botín was happy to reciprocate when, in 1999, RBS sought to make its own business-changing acquisition of its much bigger UK rival, NatWest.

The career of Fred Goodwin – chief executive of RBS at the time of the ABN Amro purchase – ended in ignominy.

Botín’s much savvier approach to the situation was the crucial reason that his bank emerged stronger from the fiasco. It helped Santander win its second global best bank Euromoney award in 2008, the year it also won best bank in the UK for the first time.

|

A unique opportunity

|

Botín with Santander’s former chief executive Alfredo Sáenz, one of a core group of lieutenants in the bank’s rapid rise |

Emilio Botín’s reputation as chairman was cemented by his victory in the Spanish central bank’s Banesto auction.

“Banesto taught us that when a unique opportunity arises, you have to take it,” he told Euromoney in 2005, reflecting on the Abbey purchase. “When we submitted the bid for Banesto, we knew we could not afford to lose the opportunity. So, we bid high. But what was €100 million to €200 million in relation to the long-term success of the business?”

It was a single-handed affair. Incredible as it might seem today, Botín apparently had to drive to the central bank in person to sign the bid for Banesto after he forgot to do so before submitting it; his fellow board members did not know the price he had agreed.

“I had spent most of the afternoon reviewing and initialling the 50-page offer document, which set out the bid terms, but when I got to the separate page where I had to put in the price, well, I simply forgot to sign it,” he told Euromoney in 1995.

Botín’s recognition of the need to gain greater critical mass in the retail market drove the high bid, says former vice-chairman Matías Inciarte.

“He had a vision that it was important to be larger in the domestic market to have the possibility for expansion outside Spain. He realized that the price was not the important issue and it had such strategic importance that he was prepared to overpay. In this sense, he was absolutely right. He was absolutely clear that Santander had to take over Banesto.”

The Spanish banking landscape, Inciarte reflects, would have evolved in an entirely different manner had Santander lost at the time to bigger rival bidders including BBV (now part of BBVA). Moreover, Botín was not risking the bank’s capital base: he could be confident it was not buying into hidden problems because the Bank of Spain had given the bidders board seats on the bank.

|

The transformational merger

At the turn of the century, when Euromoney reported on Santander’s transformational merger with Banco Central Hispano (BCH), Emilio Botín was already known as “the Pharaoh” in Spanish banking circles and “the godfather of Spanish banking”.

|

In 2000, Botín bulldozed his rivals to buy Banco Central Hispano |

Banco Santander Central Hispano, the merged entity, became the eurozone’s third biggest bank by market capitalization, behind ING and Fortis. The way Santander effectively swallowed up BCH highlights how easy it was for Botín to bulldoze his rivals. Unlike the acquisition of Banesto, this was a bull-market deal, requiring more diplomatic skills, says Matías Inciarte, who became vice-chairman of the merged entity.

“It was obvious that the merger was a good idea in terms of synergies and critical mass, and the Spanish economy was booming, so we could digest any problems,” he says. “But we needed to convince the other side that there was something positive in it for them.”

Resolving the anxieties of BCH on the executive power structure and the extent to which the merged entity would not simply be the Botín family’s bank ended up being more of a sticking point than the financial terms.

The agreement saw BCH’s chairman José María Amusátegui become co-chairman alongside Botín. In addition, while Botín had previously done without a chief executive, BCH’s CEO Angel Corcóstegui became chief executive of the merged entity.

The trickier element was the position of the family. Even then, the common assumption was that Ana Botín would eventually take over the running of Santander.

The initial plan was that she would be the merged entity’s head of investment banking. But before the merger went through, in a formative experience, she resigned from all executive positions in the merged bank. Most embarrassingly, this came just one day after an eight-page profile in Spanish national newspaper El Pais had hailed her as “the most powerful woman in Spain”.

“It was a very delicate negotiation,” Inciarte recalls. “We weren’t dealing with a bank with no alternatives. They could stand alone and Angel Corcóstegui was a good manager. They were not under pressure to go forward with that deal, and until the last minute they could have backed out. We didn’t have a lot of leverage over them.”

Tensions came to a head after a disagreement over the new brand, when Botín replaced head of communications Luis Abril, in an apparent snub to Corcóstegui. As the central bank declined to intervene in the stand-off (in contrast to a similar situation a decade earlier, when BBV was created), Amusátegui resigned shortly afterwards, two years before his formal retirement. A year later in 2002, Corcóstegui stepped down, citing personal reasons.

After a couple more years, Ana Botín was called back to be executive chairman of Banesto, then still run as a separate unit within the group, before taking over Santander UK after António Horta-Osório’s defection. Now she is executive chairman of Santander, while BCH and its brand have disappeared.

In some respects, however, the BCH merger – like Botín’s other big deals – inevitably forced Santander down a different path, not least due to the necessary dilution in the family’s holdings. BCH may also have brought a subtler change in the bank’s culture, as the “lean and aggressive” Santander merged with the “sluggish leviathan” that was still being turned around after a merger between Banco Central and Banco Hispano Americano in the early 1990s.

Corcóstegui’s personality as “a thoughtful and detail-orientated manager” contrasted with Emilio Botín, “the classic deal-maker and risk-taker”, who liked to be in total control.