When Caitlin Long tried to donate bitcoin to the University of Wyoming in 2017, she was surprised to be met with a polite but firm ‘no’. It was after all a pretty good investment: the value of the cryptocurrency jumped 20-fold just over that year.

Jump to:

Her alma mater wasn’t just being obstructive. The hitch was a piece of old legislation called the money transmitter law, which precluded crypto firms from operating state wide.

Most people would have shrugged and given up. But the Wyoming native wasn’t the type. A 22-year Wall Street veteran, Long ran Morgan Stanley’s pensions business for a decade then chaired New York blockchain firm Symbiont for two years – and she liked a challenge.

“Because of my deep connections and love for the state, my reaction was: ‘That has to get fixed,’” she says.

It has. In the space of five years, the Cowboy State, as Wyoming is known, has been transformed from an exporter of beef and base chemicals into America’s leading crypto hub and a genuine hotbed of digital financial innovation.

Today, the state is home to three crypto lenders: Kraken, Wyoming Deposit & Transfer and Avanti. All are licensed or chartered under Wyoming law as special purpose depositary institutions (SPDI – the acronym is pronounced ‘speedy’), which Long describes as the “first new type of banking charter in the United States in decades.”

Each offers its own slightly modified set of services, spanning digital asset banking, custody, payment solutions and data protection. Currently, none of the trio can lend out customer deposits or take on leverage, but all hope and expect that to change soon.

Long herself has barely stopped moving since stepping down from Symbiont in 2018. She co-founded the Wyoming Blockchain Coalition – with its stated mission of using technology to cut costs and create new business – after getting the nod from the then-governor, Matt Mead.

In February 2020, she founded and was made chief executive of Avanti Financial Group, locating it in the state capital Cheyenne, after attracting $37 million in capital from investors including the University of Wyoming Foundation.

Eight months later, Avanti applied for a Federal Reserve master account. This would give it access to the US central bank’s payments systems, cut costs and risk, and let account holders move fiat dollars directly without needing to use an intermediate or partner bank.

Taking the lead

In June, Wyoming legally recognized blockchain-based decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), run by groups who vote – on investment, direction and strategy – by deploying tokens. In November, an entity called CityDAO made history by buying land near Yellowstone National Park. Based on the Ethereum blockchain, investors have voting rights and can settle there as self-proclaimed ‘founding fathers’.

Wyoming state senate minority leader Chris Rothfuss compares Wyoming’s drive to “take the lead” on crypto with the inertia of the federal government. “There’s no question states are better at innovation,” he says. “Congress is rubbish in terms of innovating or effectively legislating, because the partisanship and vitriol is at a level where, even under the best of circumstances, they’re nearly paralyzed.”

There’s no question states are better at innovation

Chris Rothfuss, Wyoming state senate

When it comes to advancing the crypto cause, a few other names deserve credit. Chris Land, general counsel to the junior US senator from Wyoming, Cynthia Lummis, drafted the laws that oversee SPDI-chartered banks that offer custody of fiat and digital assets. David Pope is an accountant who once ran for the state senate and Matthew Kaufman is an attorney who advises investors and corporates on blockchain, cryptocurrency and token offerings.

Along with Rothfuss and Tyler Lindholm, a former member of the Wyoming House of Representatives who is now state policy director for senator Lummis, the trio was heavily involved in creating the blockchain taskforce and all have served at some point on its advisory committee.

“It takes a core of truly committed policymakers to have a vision for what they want to accomplish,” says Robert Baldwin, head of policy at the Washington-based Association of Digital Asset Markets. “This group put its heads together in 2018 to 2019 and created something really substantive. A ton of thought has gone into what Wyoming is doing.”

The US is often heralded as a hotbed of digital financial innovation. And it is home to a number of pioneers, from Marqeta, which issues cards to the likes of Uber, to Varo, a neo-lender that secured a full-service national bank charter in 2020 from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), an independent body inside the US Treasury department.

Falling numbers

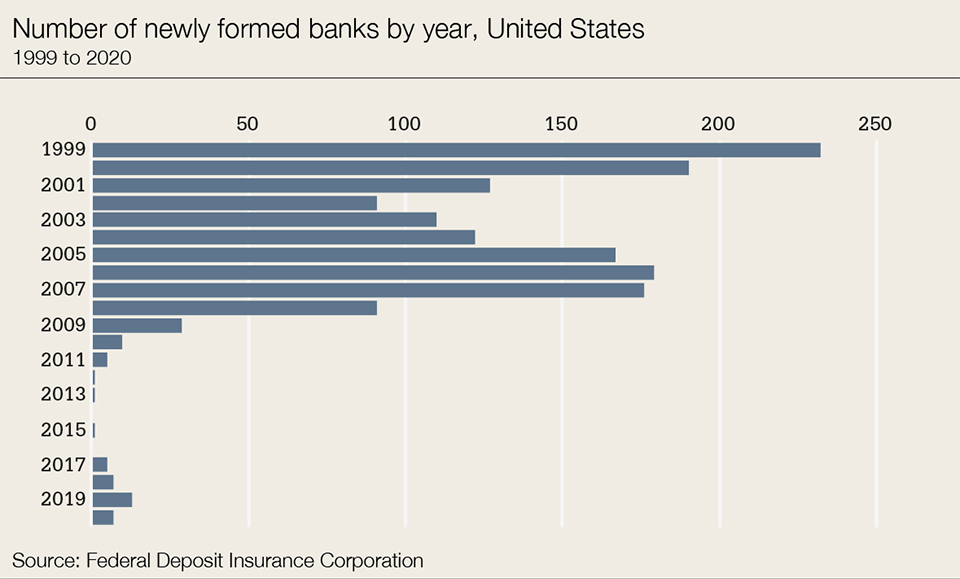

However, the reputation doesn’t always match reality. The number of commercial banks has been falling for years. In 2020, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the US had 4,377 banks, a third fewer than existed a decade ago.

Yet regulators have been loath to dish out charters, particularly to neobanks. Among their many duties, the FDIC and OCC are responsible for issuing new operating licences, something both agencies were once more than happy to do.

In the run-up to the global financial crisis, it was creating between 100 and 200 new banks a year. But after 2010, that number flatlined and hasn’t really recovered. Long says securing a new charter is: “A harder process than it should be. But there are good reasons why it is a very difficult process. It requires a lot of capital. It is in the best scenario an 18-month process but [in reality] much more likely to be take more than two years.”

Legal wrangling has also stymied development. When the OCC set out plans to issue federal bank charters to fintech companies that do not accept deposits, it ran into trouble. New York’s top banking regulator, the Department of Financial Services (DFS), sued the government, calling the decision “lawless”, “ill-conceived” and financially destabilizing.

That decision was backed by the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS), which represents bank regulators from all 50 states. The suit – which has since been dropped – claimed the agencies lacked authority to create a new kind of bank. “The big mistake was the new charter wasn’t crystal clear,” adds a source close to the issue.

The result is that despite America boasting thousands of fintech companies, hardly any of them have a master account with the Federal Reserve. (Denver-based Reserve Trust does, but there is no definitive list, as the Fed does not disclose who has master accounts).

Learning lessons

Wyoming didn’t want to suffer the same fate. Its cross-party crypto believers knew that to be the nation’s digital asset heartland it must learn from the mistakes of others.

From the start, state legislators were meticulous in their prep work. “This was a long process,” says Long. “The origins of the SPDI charter date back four years. It has been a long process to get where we are today, involving a tremendous amount of work.”

Lawmakers didn’t just throw together legislation in the hope it would somehow stick. They assembled a two-stage plan with care and forethought. Step one was to frame the rules that would grant licences to and oversee SPDI-chartered financial institutions.

“Wyoming’s thinking was really critical and careful,” says Baldwin. “They worked everything through: legal clarity in case of the bankruptcy of a crypto bank, how a wind-down would happen, even DAOs. They put together an 800-page handbook. It’s a highly detailed examination of how crypto banks will work and how they should be regulated.”

There’s less settlement risk for the end user if a financial institution can bank directly with the Fed… Once you bank directly at the Fed, you take all of that risk off the table

Caitlin Long, Avanti

Long stresses the weight of this point. “When you set up a new type of financial charter, you need three things: clear statutory authority, clear rules that have gone through a public comment process and a supervisory exam manual that the regulator is trained to apply.

“That is a very heavy lift and it is a multi-year process,” she adds. “It took Wyoming two years just to get those three things in place. It’s an alphabet soup of agencies that has been working on this. We’ve had a very active dialogue with the Federal Reserve all along.”

But that’s just a precursor to step two, which is to secure a master account at the Fed. This is the Holy Grail and the whole point of all this careful planning.

The value of a master account to Wyoming’s crypto lenders cannot be overstated. It would give them direct access to the Fed’s payments systems. That would allow them to settle transactions with other lenders in central bank money and let account holders move fiat dollars directly, without having to resort to using an intermediate or partner bank.

That’s the whole ball game for crypto, says Long. “There’s less settlement risk for the end user if a financial institution can bank directly with the Fed. If it can’t – as is the case with most fintech companies in the US – it has to go through a partner bank to declare its US dollar payments, [which] means delay, cost and counterparty risk. Once you bank directly at the Fed, you take all of that risk off the table.”

Slow progress

Today, most banks refuse to touch crypto, in large part because it’s deemed a high-risk industry. “Unless a bank actively seeks to specialize in serving the industry, it will stay away, as it sees the risk as outweighing the reward,” says one crypto investor. “It’s not an industry banks just dabble in, as the compliance costs involved in serving it without getting into potential regulatory trouble are so high.”

The upshot is that a master account with the US central bank would let Avanti and its peers bridge the real/virtual financial divide, enabling a customer to, say, sell bitcoin or Ethereum, then bank it in fiat US dollars.

Crypto banks can ask for a master account from any of the Fed’s 12 reserve banks. Avanti’s application has been pending since October 2020. Julie Fellows, co-founder and chief executive of Wyoming Deposit & Transfer (WD&T), insists it is high on her to-do list. “We have begun the process and look forward to working together with the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City to obtain our master account,” she says.

The OCC and Federal Reserve are large organizations that don’t move fast

Julie Fellows, Wyoming Deposit & Transfer

What’s to stop any of the 12 regional banks in the Fed’s reserve system from approving one or all of the applications today?

Well, for one thing, the Fed isn’t known for being nimble. It thinks deep and acts slow. Rothfuss describes it as: “Even under the best of circumstances, a glacially slow creature that does not favour innovation or change.”

Of course not all inaction denotes inertia. “They need to understand where the risks are and to mitigate and manage those risks,” says Fellows. She points to her history as a national examiner at the OCC, where she spent seven years in the 1990s.

“The OCC and Federal Reserve are large organizations that don’t move fast,” she adds. “They’re going to have to train their examiners to understand this new area. And it’s not easy. It is a completely new way of thinking about things.”

Some within the Fed have very clearly nailed their colours to the mast. In August 2021, the president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, Neel Kashkari, called crypto: “95% fraud, hype, noise and confusion.”

Nevertheless, Wyoming’s crypto banks believe securing a master account is only a matter of time. “We remain optimistic we will be granted both the master account and [Federal Reserve System] membership applications,” says Long. “It’s just a question of when.”

“We aren’t offering something really ‘out there’ on the risk profile,” adds Fellows. “And because we have a strong understanding of what it takes to create that infrastructure for a well-regulated, safe and sound entity, I’m really optimistic of moving through the Federal Reserve application process pretty quickly.”

In truth, there is risk on both sides here. If the Fed approves a single master account, it opens the door to dozens – in time hundreds – of crypto firms to become banks licensed to take deposits and disburse loans.

Lee Reiners, executive director of the Global Financial Markets Centre at Duke University School of Law in North Carolina, is also a former official at the New York Fed and a self-declared crypto sceptic. He warns that once a stable door is open it is hard to shut.

“This is my main concern,” he says. “If the Fed approves [master accounts], it will integrate crypto into the banking system and create new contagion channels for problems in the crypto sphere to spill over into the broader financial system.”

He adds: “We may look back in five or 10 years and say: ‘This was the key moment, when crypto became integral to the economy.’ If there is some kind of price disruption, it can spread contagion fast through the economy. And it’s hard to see those connections until after the fact. No one [in 2008] knew AIG had massive exposure to the mortgage market.”

We remain optimistic we will be granted both the master account and [Federal Reserve System] membership applications. It’s just a question of when

Caitlin Long, Avanti

It’s the classic two-horned dilemma. On the one hand, the longer crypto hangs around and the more mainstream it gets, the harder it is for the Fed to resist granting master accounts. Conversely, if it waits a little bit longer and crypto crashes and burns, it will feel vindicated.

But even if the Fed and the alphabet soup of agencies vying to oversee crypto – including the OCC, Commodity Futures Trading Commission, CSBS, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and FinCEN (another part of the Treasury), not to mention state regulators like the Wyoming Division of Banking and New York’s DFS – fail to figure out a legislative roadmap, other risks, predictable and unforeseen, will surely crop up anyway.

At present, a handful of lenders – notably San Diego-based Silvergate and New York-based Signature – specialize in serving the crypto space.

“That is not enough; I can’t think of another industry that is so underserved by banks,” says Long. “Most banks stay away from high-risk industries unless they choose to specialize in them. So first and foremost, we want to provide US dollar banking services to this industry so that we can start to attack that concentration risk issue.”

Stonewalling

WD&T’s Fellows says a more systemic risk is the US will get left behind, out-innovated by fintechs and regulators in Europe and Asia.

“The initial risk is the US no longer being a hub for innovation, so investment capital and companies move to a place that is more supportive. There will be broader implications if other countries adopt different processes and we are completely left out of it. So I think that is driving additional urgency for [federal agencies] to get up to speed,” she says.

“The US can’t be left without these services. We really believe this is helping to improve the democratization of wealth creation. There’s so much untapped value here for the broader population.”

Among crypto’s growing army of adherents, there is longstanding of suspicion that Wall Street, fearful of being supplanted by decentralized finance, is in Washington’s ear whispering about risk and stoking fears over pro-crypto legislation.

“The cynical side of me says some portion of the delay [in granting master accounts] is because large traditional financial institutions don’t want to see disruptive innovation because they make money hand over fist, day in and day out,” says Rothfuss.

Fellows echoes this point. “There is a lot of pressure from the existing banking infrastructure, which doesn’t want this to move forward because they recognize that, quite frankly, we’re going to eat their lunch,” she says.

“Most of the big US banks have gone through a number of mergers and their systems are a mess. They spend millions a year just trying to keep things working. They cannot quickly implement the type of technology that can provide the services that we will be able to.”

There is a lot of pressure from the existing banking infrastructure, which doesn’t want this to move forward because they recognize that, quite frankly, we’re going to eat their lunch

Julie Fellows, Wyoming Deposit & Transfer

It is surely just a matter of time before the Fed approves master accounts, starting with Wyoming’s crypto trailblazers. A lot of Washington insiders are on the fence about crypto, but it attracts new devotees all the time. Republican senators Patrick Toomey and Ted Cruz own bitcoin, as does Arizona Democrat Kyrsten Sinema.

Every month, it gets harder for federal agencies to stonewall applications and generally, as Rothfuss puts it, “slow roll” the process. Writing in the Wall Street Journal in November 2021, Wyoming senator Lummis noted the “more than 100 meetings” between state legislators and the board of governors of the Kansas City Fed.

“Is an SPDI a bank?” she asks in her op-ed, then answers her own question. “Without a doubt. It’s eligible for deposit insurance and receives deposits relating to custodial and fiduciary activities – meeting the standard Congress set down in the Federal Reserve Act for what constitutes a bank.”

This is often how innovation in America works. The former US Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis, once called individual states “laboratories of democracy”, where economic ideas are trialled before being either shut down or set free to flourish on the national stage.

What of Wyoming itself? This place of proudly self-reliant libertarians has spent the past five years flying the flag for crypto. Can it maintain its lead or will it be outflanked by bigger and better-funded states?

No, or not for a while at least, reckons Fellows. “Because it is smaller, it can actually get things done,” she says. “Others – Colorado, Texas, Illinois – have looked at creating an [SDPI-like] banking charter, but they don’t have the infrastructure in place. Wyoming will be a front runner for at least the next few years.”

Baldwin at the Association of Digital Asset Markets isn’t so sure. “These rules can be replicated elsewhere,” he says. “Connecticut is updating rules relating to crypto. So is Texas. Colorado wants to be a hub for a new wave of digital financial technologies.”

In October 2021, Miami announced a taskforce to examine the feasibility of accepting tax payments in the form of cryptocurrencies.

For now, the lead is Wyoming’s to lose. Rothfuss reckons the key to it all was the decision by a core group of crypto believers to put strong foundations in place from day one.

“This was a real opportunity for us to take a leadership position and innovate: to support this emerging technology instead of being restrictive like many other states,” he says. “Normalizing [crypto], wrapping sound regulation around it, acknowledging risk, putting in place rational consumer protections that aren’t reactionary but are thoughtful and appropriate instead of prescriptive – those are the kinds of things we’ve really embraced.”

Why Wyoming?

It is curious that in the world’s largest economy, crypto found its natural home, not in Texas, California or New York but a sparsely populated and beautiful sweep of prairie land that generates less economic output than any state in the union, bar Vermont.

There are several answers to this and they are all fascinating.

The cliché of Wyoming as one of America’s so-called ‘flyover’ states, where a whole lot of nothing happens, is easy to fall back on. But it’s also a conscious bias that happens to be wholly untrue.

Delaware is the state most closely associated with limited liability companies (LLCs): hybrid firms that protect owners from personal responsibility for debts or liabilities. It’s the reason so many big US firms choose to incorporate in that tiny slice of the eastern seaboard.

Actually, the first LLC was created in Wyoming. One of only two states – the other is South Dakota – with no corporate or personal income tax, it has long struggled to fill its coffers. After dodging bankruptcy in the 1960s, it cast around for new sources of revenue and in 1977 state legislators created the first LLC for an out-of-state oil company. It is still a major income generator today.

“We are right behind Delaware in terms of new business entity registrations,” says Avanti’s Caitlin Long. “Back then, everyone thought we were crazy. They laughed. How dare we create a new type of legal entity. But Wyoming did the work and got it approved. And within 10 years, every US state had LLC laws.”

And it continues to innovate. At the end of June 2021, Wyoming was home to 48 LLCs with ‘Bitcoin’ in their name, against 31 in California.

Rebellious streak

Crypto also taps directly into the rebellious streak that runs through a deeply libertarian state that values self-reliance, privacy and equity. Crypto ticks a lot of boxes for a lot of people, says Lee Reiners at the Global Financial Markets Centre. “It’s all about independence – owning your own financial data and your future.”

Local lawmakers picked up on this early. In 2013, Cynthia Lummis, then a two-term member of the US House of Representatives, was turned on to crypto by her future son-in-law. Today she owns five bitcoin, collectively worth a little under $180,000.

By any measure, Lummis, elected to the US Senate last year, is a crypto believer. She once Photoshopped laser eyes onto her Twitter profile, with the aim of boosting bitcoin’s value. She has called the digital currency “freedom money” that liberates people from the yoke of inflation.

And she is far from alone in her views. Wyoming senator Chris Rothfuss picks up on the theme, describing crypto as “technology that democratizes financial transactions and gives it back to the people.”

When we speak, Rothfuss is in his pick-up truck, driving the 45 miles across a snow-clad mountain range between Cheyenne and his home in Laramie. A polymath who holds three postgraduate degrees, including a PhD in chemical engineering, he is also co-chairman of the blockchain taskforce as well as Senate minority leader in Wyoming’s State Legislature.

In his view, Wyoming is the home of US crypto precisely because of the preponderance of libertarians. “It transcends party beliefs,” he says. “It’s why we’ve been able to pass more than 25 laws related to digital assets.”

Rothfuss points to work he has done to promote digital asset innovation with Tyler Lindholm, state policy director for Lummis.

“Tyler is a libertarian-style Republican and I am a libertarian-style Democrat,” he says. “We have a lot of areas of commonality of belief: in privacy, autonomy, the kinds of things digital assets can provide more access to.”

This isn’t merely lip service. Wyoming’s legislature passes a new crypto law pretty much every couple of months – not bad, given that in any two-year span it is only permitted to sit for up to 60 days.