The People’s Republic of China rarely passes up the chance to burnish its credentials as a supporter and funder of the developing world, a role that is deeply ingrained in its collective psyche.

In March 2021, foreign minister Wang Yi said China would “always support” developing nations. During a trip to Kenya in the first week of 2022, he urged the international community to “pay more attention to Africa” – and to learn from China, which had “done more” for the continent than the developed west.

The most obvious physical manifestation of this is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), championed by president Xi Jinping, which now encompasses 42 nations in sub-Saharan Africa, 20 in Latin America, and most of central Asia and central and eastern Europe.

Through the BRI, China came to see itself as not just an ideological advocate of the developing world but also its financial champion. So did leaders of poor and rich nations alike.

However, two years and counting into the Covid era, Chinese overseas lending to the developing world has collapsed.

The Asian Development Bank reckons China-led foreign direct investment (FDI) into Asia including Japan halved between 2019 (when it totalled $56.6 billion) and 2020 ($29.7 billion).

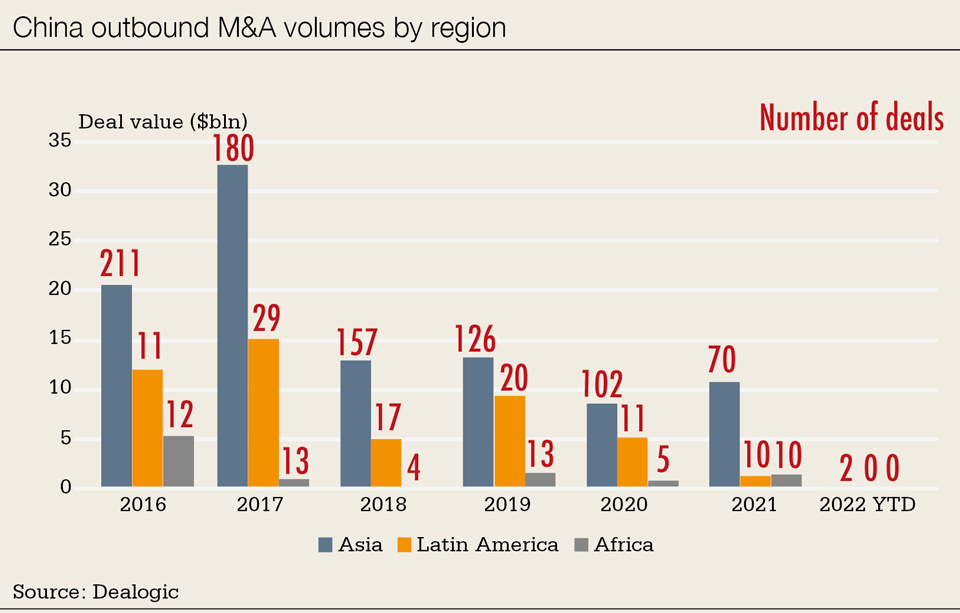

Outbound M&A is also down across the board. In volume terms in 2017, mainland corporates accounted for $32.7 billion in Asia ex-Japan M&A deal-flow, according to Dealogic. In 2021, that number was $10.8 billion.

The same pattern is visible in Africa, where deal-flow fell from $5.24 billion in 2016 to $1.38 billion in 2021, and Latin America, down from $15 billion in 2017 to $1.25 billion in 2021.

Just 12 outbound M&A deals, worth a total of $915 million, were completed in the world ex-Europe and North America in the first six weeks of 2022. Yes, the year is still young, but domestic banks like to open the lending taps early, and January is a reliable barometer of how the state plans to put its money to work in the first half and beyond.

Is China indeed pulling back from the world? Or is this just a hiatus

Then there is the Middle East, a mix of developed and developing markets. According to Natixis, mainland capital flows into the region have all but shut down, falling from $5.2 billion in 2016 to $100 million in 2020. Covid hastened this process, but didn’t cause it: China-led investment in the Middle East was just $300 million in 2019, according to data from Mergermarket and the American Enterprise Institute.

Add to the mix Beijing’s zero-Covid strategy and closed borders, and it doesn’t seem a stretch to conclude that outbound FDI and M&A volumes will stay suppressed and may well sink further during the next 12 months.

Then there is the curious case of Latin America. Beijing has spent much time and effort courting banks, corporates and heads of state in the region.

Mostly, it has worked. When Argentine president Alberto Fernández visited Beijing in early February, in the-run up to the Winter Olympics, he came laden with compliments.

He praised the “magnificent architecture” of the Party’s own museum. As his delegation departed a televised meeting with Xi, an aide declared that “without the Communist Party, there would be no new China”, to Xi’s palpable delight.

For his part, Fernández likely saw it as a cheap win. His visit came days after the IMF agreed to restructure a $57 billion loan for the Argentine Republic, averting a looming default.

Doffing the cap to Beijing secured admittance to the BRI. Argentina is the first big Latin American economy to join the project and the ninth overall. Later, Fernández said: “Our country will obtain more than $23 billion from Chinese investments for works and projects.”

China, pointedly, made no formal financial commitment to its new BRI brother. Xi pledged to complete existing hydropower and railway projects, and to “deepen cooperation” with Argentina in trade and anti-epidemic efforts.

However, reality and recent data suggest Buenos Aires will be lucky to get more than a sprinkling of cash out of Beijing.

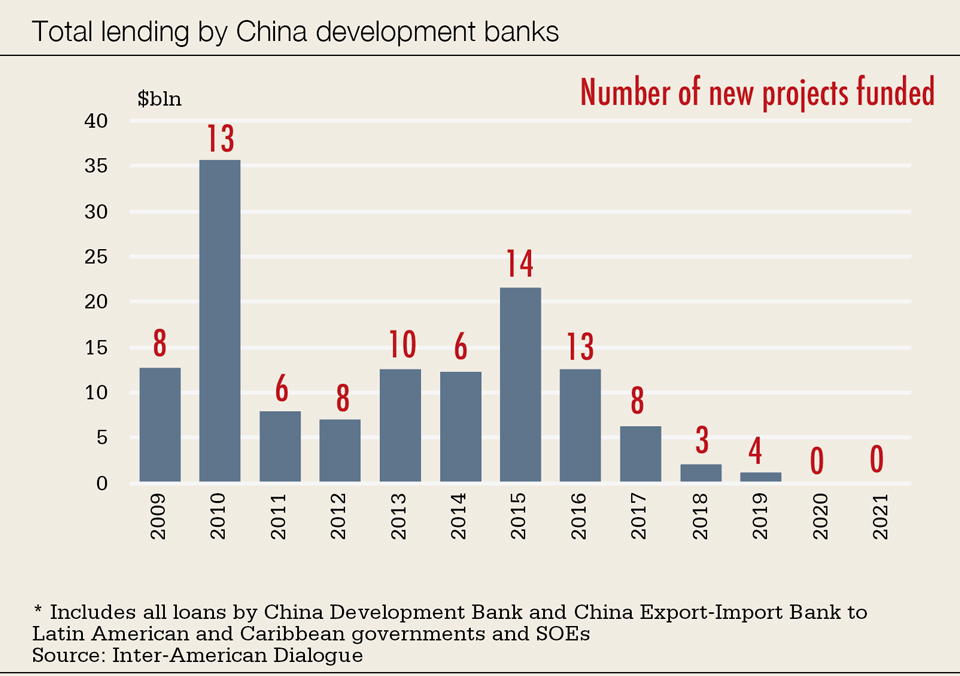

The Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based non-profit, tracks lending by China Development Bank (CDB) and Export-Import Bank of China to Latin American and Caribbean sovereigns and state-owned enterprises.

Total lending peaked in 2010 at $35.7 billion, and again in 2015 at $21.5 billion. It then slowed sharply – before coming to a complete halt. In 2020 and 2021, the big-two policy banks channelled exactly no new dollars to any projects at all in Latin America.

Perfect storm

So, what is happening here?

It is not a case of one thing going wrong, but many: the proverbial perfect storm.

China in the early 2020s is not the China of a decade earlier. There is still a lot of money sloshing around in its coffers, but less than before. Its foreign exchange reserves topped $4 trillion in 2015, but have since plateaued at around $3.2 trillion.

Moreover, Asia’s largest economy is stuttering. In 2010, output expanded 10.6% on an annualised basis. In 2020, the first year of the pandemic era, it grew 2.3%.

The IMF tips GDP to come in at 4.8% this year, with property-sector pressures acting as a prelude to a broader decline. The zero-Covid policy, which includes locking down cities and keeping foreign workers out, is likely to further temper growth.

Beijing has reacted by redirecting capital from foreign to domestic projects. While logical, it means it has less cash to put to work beyond its borders.

“Addressing the pandemic and economic slowdown at home means the abundance of capital that fuelled the BRI isn’t there anymore,” says Yunnan Chen, a China-Africa expert, and senior research officer at ODI, a London-based global affairs think tank.

Added to which, China’s policy banks have been hit by a series of scams and scandals.

In September, the nation’s top graft-busting agency put CDB vice-president He Xingxiang under investigation for alleged “severe discipline and law violations”. It came eight months after the bank’s former chairman Hu Huaibang was sentenced to life in prison for taking $13 million in bribes.

“Corruption cases at home have increased scrutiny of the lending institutions, which halted disbursements in 2019,” says Chen. Xi’s anti-corruption drive is “further delaying new loan approvals”, adds Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist, Asia-Pacific at Natixis.

Add to that damning accusations, mostly emanating from western officials and non-governmental organizations, that China is turning poorer nations into client states by loading them up with unpayable levels of debt.

“The narratives around debt-traps have not helped with the optics of Chinese lending abroad,” notes ODI’s Chen. “There is also more risk-aversion from lenders in financing certain sectors and projects overseas.”

Dead or alive?

So, what happens now? Is China indeed pulling back from the world? Or is this just a hiatus, with Beijing biding its time until the pandemic ends and its borders open?

Chen skews more toward the latter view. Asked if the BRI project is dead, she replies: “No, because anything can be called the belt-and-road. It can be based on investments in digital, in payments, in renewables. Really, anything with people-to-people or cultural exchanges are pooled under BRI, so it can all be repackaged.”

There is plenty of evidence that, stung by debt-trap accusations, the Party has used the past two years to reconfigure how it lends overseas and to whom.

“There is definitely evidence of a shift in where finance is going,” adds Chen. “China seems to have a more specific and targeted approach. Its financial institutions are learning, recognising past mistakes and errors, and taking a more risk-averse approach to what projects they finance, and how they go about financing and due diligence.”

This means less direct state-to-state and state-to-project funding, and more indirect lending, via smaller development outfits such as Cairo-based African Export-Import Bank, and the Burundi-based Trade and Development Bank.

Natixis’s Garcia-Herrero reckons the reverse is true. In her view, Beijing’s foreign-capital commitments are on a long-term decline, having peaked across the world around 2016.

“If you talk to senior [mainland] officials, they will say: ‘This is China retrenching’. And it is: China is retrenching big time, not on the power side but certainly on the funding side.”

She adds: “They are increasingly using words not deeds; using political power, but the money isn’t there behind it. I don’t believe China’s influence will get any bigger overseas. We have passed peak China.”