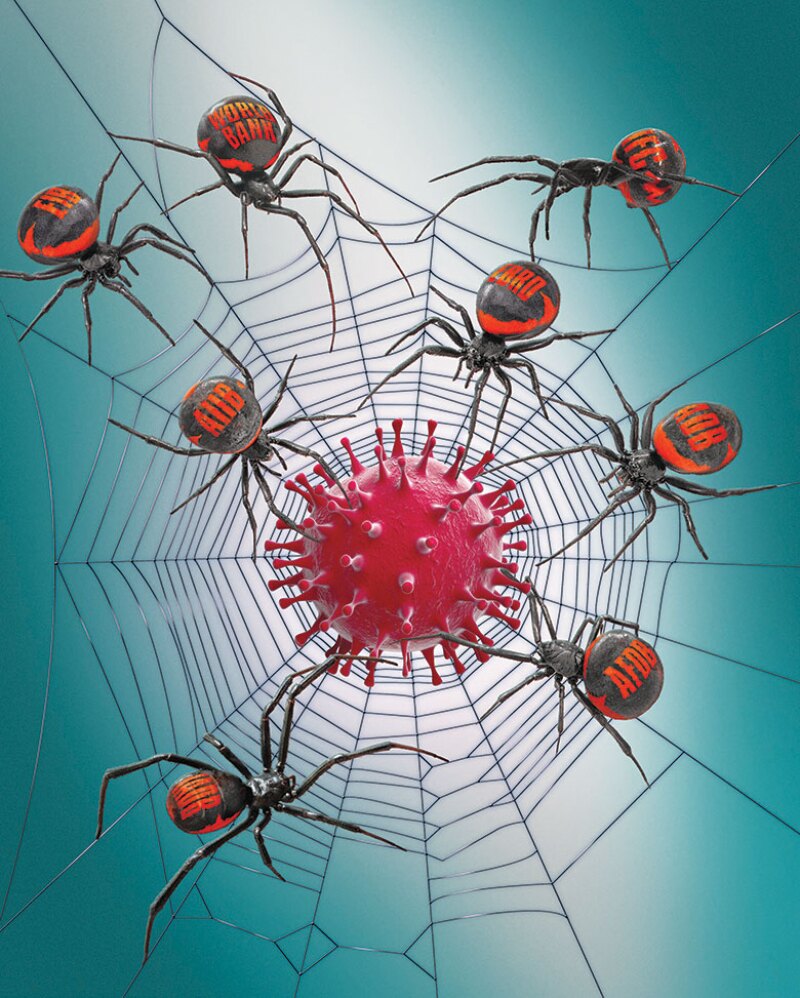

Illustration: Jeff Wack

Multilateral development banks exist for these moments. Events like the Covid-19 pandemic can define young MDBs and inject new life into veteran institutions.

This can cut both ways. After the Arab Spring, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development swiftly expanded its reach into North Africa, providing financial aid and stability. However, the global financial crisis was more of a mixed moment for multilaterals.

In a World Bank report published in late 2009, the MDB accused itself of being “surprised” at the scale and speed of the Lehman Brothers shock and of taking “several months” to develop a coherent strategy.

This time, the World Bank isn’t going to be caught napping.

Now is the time to streamline the processing of financial assistance and get rid of red tape - Jin Liqun, AIIB

On April 2, it announced plans to deploy $160 billion over the next 15 months to bolster global growth, support small and medium-sized enterprises, and protect the poor and vulnerable.

Of the total, $50 billion is to be channelled to less-developed countries by the International Development Association (IDA), the division of the World Bank that helps the world’s poorest countries.

A further $80 billion in funding will be committed by regional multilaterals: the EBRD, Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank (AfDB), Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and European Investment Bank (EIB), as well as the new kid on the block, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

That brings the total to $240 billion.

Each MDB faces the same basic set of questions. How fast can it scale up lending? Is $240 billion enough to tackle this unprecedented challenge? Where will the funds go, and can they be put in the hands of those who need them most quickly and efficiently?

|

Jin Liqun, |

A systemic crisis like this, AIIB president Jin Liqun tells Euromoney, forces international financial institutions “to act – and act quickly. Now is the time to streamline the processing of financial assistance and get rid of red tape.

“It is crucial to be creative, innovative and cooperative in rendering effective support to their members.”

So far, that’s exactly what they’re doing.

From the start, Washington chose to take the lead on coronavirus. Each week the heads of all the big MDBs take part in a virtual get-together led by either World Bank president David Malpass or IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva.

“We do a tour [of the] table and talk about the many challenges we have,” says the president of the IDB, Luis Alberto Moreno.

It’s an invaluable chance for MDB chiefs to talk frankly and openly to their peers.

Symmetry is sought, as multilaterals seek to identify what country or project needs its help most, then crowd as much capital into it as fast as possible.

Asia

What emerges from the frantic weeks of recent activity is a spider’s web of projects. Some overlap while many are country- or region-specific.

Between December 31, when the outbreak was first reported by China to the World Health Organization, and April 14, the World Bank approved $12.6 billion in new lending, with $3.1 billion for low-income countries, according to data from the Center for Global Development (CGD), a London and Washington-based think tank.

Both figures are slightly higher than the equivalent numbers a year ago – $10.5 billion and $2.6 billion.

Another $18.5 billion in World Bank lending is in the pipeline for the rest of 2020, although that will rise to meet soaring demand for capital from all quarters.

New loans approved by the IDA in the year to April 14, earmarked for the poorest nations, total $3 billion, with a primary focus on Africa and south Asia.

The first batch of loans, part of the World Bank’s new fast-track facility response, sets out to “save lives and help detect, prevent and respond to Covid-19”, according to its head of operations Axel van Trotsenburg.

It includes aid for the poorest countries in every region, such as Haiti ($20 million), Yemen ($26.9 million), Afghanistan ($100 million) and the Kyrgyz Republic ($12.2 million).

We will support domestic and cross-border trade, and increase access to working capital and local currency financing - Tomoyuki Kimura, ADB

Every region of the world is in a perilous position, but each is working to a different coronavirus chronology and a distinct set of challenges.

Asia, hit first and hardest, is at one end of the time spectrum. On April 13, ADB president Masatsugu Asakawa unveiled an expanded $20 billion financing package to tackle coronavirus.

Around $6.2 billion of this ‘new’ capital already exists – it was simply redirected from projects stalled or scrapped in early 2020. Within five days it had disbursed $66.5 million in loans to projects in 28 countries.

Like its peers, the Manila-based ADB wants member states to be equipped with enough medical equipment and testing facilities. But with new cases falling sharply in April in China and Korea, the emphasis will switch to supporting small businesses, tackling joblessness and getting economies back on their feet.

In Asia, the workshop of the world and a region filled with countries reliant on cyclical income from remittances and tourism, a key focus is the private sector. The ADB’s expanded package includes $2.5 billion in concessional and grant resources and $2 billion to support the private sector across emerging Asia.

|

Tomoyuki Kimura, |

“We will support domestic and cross-border trade, and increase access to working capital and local currency financing,” says the director general in charge of strategy, policy and partnerships, Tomoyuki Kimura.

While most of the funding is short-term in nature, “this is what is needed most at the moment,” he adds.

Asia’s new multilateral, the AIIB, is taking a different tack as it aims to learn from its first external crisis and put its capital to good use. On April 19, it doubled the size of its Covid-19 Crisis Recovery Facility to $10 billion.

So far, some of its actions are like those of a typical development bank. It is working with the ADB to extend fiscal and budgetary support to member states (including 35 non-Asian sovereigns) and to channel capital to Asian banks that then on-lend to struggling sectors and clients.

But in line with the AIIB’s name and identity, its chief aim is to build infrastructure – a useful goal at a time when everyone needs more hospitals and clinics.

Since the start of April the bank has disbursed $170 million to improve sanitation in the Bangladesh capital, Dhaka, and $355 million to China to upgrade its public health system.

The AIIB is also reviewing a host of existing projects with other MDBs, including a $500 million loan to strengthen India’s health system and a $250 million loan to make Indonesia more pandemic-ready. Both are co-financed with the World Bank.

Latin America

At the other end of the time spectrum is Latin America. Coronavirus arrived there later, and is unlikely to peak until at least late May, according to IDB chief Moreno. That may be both a curse and a blessing.

On the plus side it has given the region time to adapt and the world a chance to find effective treatments.

Yet Latin America is also in a weaker state than it was the last time a global crisis hit in 2008, the IDB admits.

Its chief economist Eric Parrado believes the region will suffer “an economic shock of historic proportions”.

The worst scenario involves a 14.4% fall in economic output in the three years to the end of 2022.

Moreno says there are opportunities for the IDB and World Bank to work together to fund countries where banks’ credit limits have been hit.

“Specifically with rapid-disbursement policy-type lending, which are typically associated with reforms, [working together] can help make disbursements quickly,” he says.

In a moment of unprecedented global crisis, recognizing the backstop value of this capital makes sense - CGD

He notes that capital, like the coronavirus, has no sovereign loyalty and moves across borders with impunity. The IDB is working hard to maximize financial support from the World Bank and two European national development agencies, Germany’s KfW and France’s AFD.

But Moreno fears that some global banks may follow their 2008 playbook and redeploy capital out of the region as shocks emerge at home. To that end, the IDB is channelling more capital into trade finance, to help support jobs, companies, and regional and smaller banks.

Latin America’s multilateral is dedicating $12 billion to fighting the virus, including $3 billion to tackle a looming healthcare crisis.

A $2 billion, five-year sustainable bond, priced on March 30, helped top up the pot. It is working both alone and alongside the World Bank to channel additional funding of $1.7 billion to countries in central America in 2020.

Africa

Africa perhaps faces the greatest existential threat from the coronavirus, where the activities of the global and regional multilaterals interplay and overlap.

Most of the continent’s countries are poor by European or east Asian standards; its supply chains are brittle and localized; and many of its banks, while solidly capitalized, are vulnerable to shocks.

The problems are immense. The African Union warns of 20 million lost jobs and the WHO of up to 10 million coronavirus cases over the next six months. The World Bank forecasts economic output in sub-Saharan Africa to shrink by up to 5.1% in 2020.

With agricultural output set to shrink by up to 7% this year and food imports likely to contract by as much as a quarter, not to mention a locust crisis in east Africa, the World Bank warns that Covid-19 could create a severe food security crisis.

For all the problems elsewhere, it’s little wonder the eyes of the development community are fixed on Africa.

|

David Malpass, |

Speaking in mid April, World Bank chief Malpass said of the 100 countries it would have working Covid-19 projects in by the end of the month, “most of them” will be in sub-Saharan Africa, with a particular focus on the Sahel and the Horn of Africa.

Of the $9.51 billion in total IDA loans, approved and pending, since the start of 2020, $5.17 billion or 54% is earmarked for projects in just four African states: Ethiopia, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda, according to CGD data.

The first Covid-19 loans by the IDA were disbursed in April to Ethiopia and Congo to train medical staff and boost health system capacity.

The IMF is busy “providing financing as quickly as possible,” says the director of the Fund’s African department, Abebe Aemro Selassie.

He says “at least 20 countries from sub-Saharan Africa have requested additional financing” via the IMF’s rapid credit facility, which offers concessional financial aid to any low-income country, equal to 50% of its IMF quota.

The IMF was an early mover on coronavirus. On March 4, it made $50 billion in fast-disbursing financing available to low-income countries, $10 billion of it at zero interest.

Selassie says a “a coordinated response” to the crisis is “essential”, adding that the IMF is working closely with the WHO and World Bank to ensure they “dovetail together” to provide coordinated support to needy countries.

On April 8, the African Development Bank rolled out its Covid-19 Response Facility to provide up to $10 billion to governments and the private sector.

|

Akinwumi Adesina, |

AfDB president Akinwumi Adesina says the package included $5.5 billion to support regional sovereigns and $1.35 billion to bolster private-sector firms and banks. On March 27, the bank printed a Fight Covid-19 social bond, raising $3 billion and marking the supranational’s largest-ever US dollar deal.

Elsewhere, the European Investment Bank has unveiled €5.2 billion in emergency funding for its non-EU operations. Most will be deployed in Africa to improve the state of its health sector and provide liquidity via local banks to SMEs.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private-sector arm of the World Bank, is focused on the disbursal of $8 billion in fast-track financing to 300 of its most needy clients; while on April 23 the EBRD expanded the size of its Covid-19 Solidarity Package to €4 billion from €1 billion. The first approvals were announced on April 16, when the London-based multilateral allocated $150 million in trade finance facilities to three banks in Uzbekistan.

Two big questions

So far, in the face of the second great crisis of the 21st century, the development community has successfully stepped up to the plate. Two big questions loom in the medium term.

First, can global policymakers convince interested parties – from sovereign states to institutional investors and the multilateral community itself – to pause debt repayments for the world’s poorest countries?

It won’t be easy, but the issue won’t go away: Ecuador and Zambia have been forced to seek debt restructurings; more will follow.

Second, is the total amount pledged by all multilaterals over the next 15 months to tackle Covid-19 – $240 billion – enough?

While a big figure, it is unlikely to stretch the finances of the development community. Most MDBs including the World Bank and the AfDB entered this crisis with their finances in better shape than ever.

Writing on March 26, the CGD noted that if you include their ‘surge’ capacity of $531 billion, five of the largest multilaterals had the collective ability to lend “in excess of $1 trillion”. That would double their current aggregate exposure.

However, that would require a shareholder of a multilateral to recognize the underlying value of its backstop as callable capital. No MDB has ever had to draw on that capital, in part because no MDB has ever threatened to default on its debts.

But is it time to rethink policy, given that the World Bank’s callable capital makes up 94% of its total subscribed capital?

“In a moment of unprecedented global crisis, recognizing the backstop value of this capital makes sense,” the CGD wrote.

In a year that has brought us pandemics and locusts, that could happen.