After yet another bout of economic turmoil, something like calm is returning to Egypt’s financial sector. There will be, of course, a period of adjustment. A noxious combination of poor policy and external shocks left the country facing record inflation, a growing debt crisis and a crippling shortage of foreign currency. The measures to prevent collapse have been understandably severe.

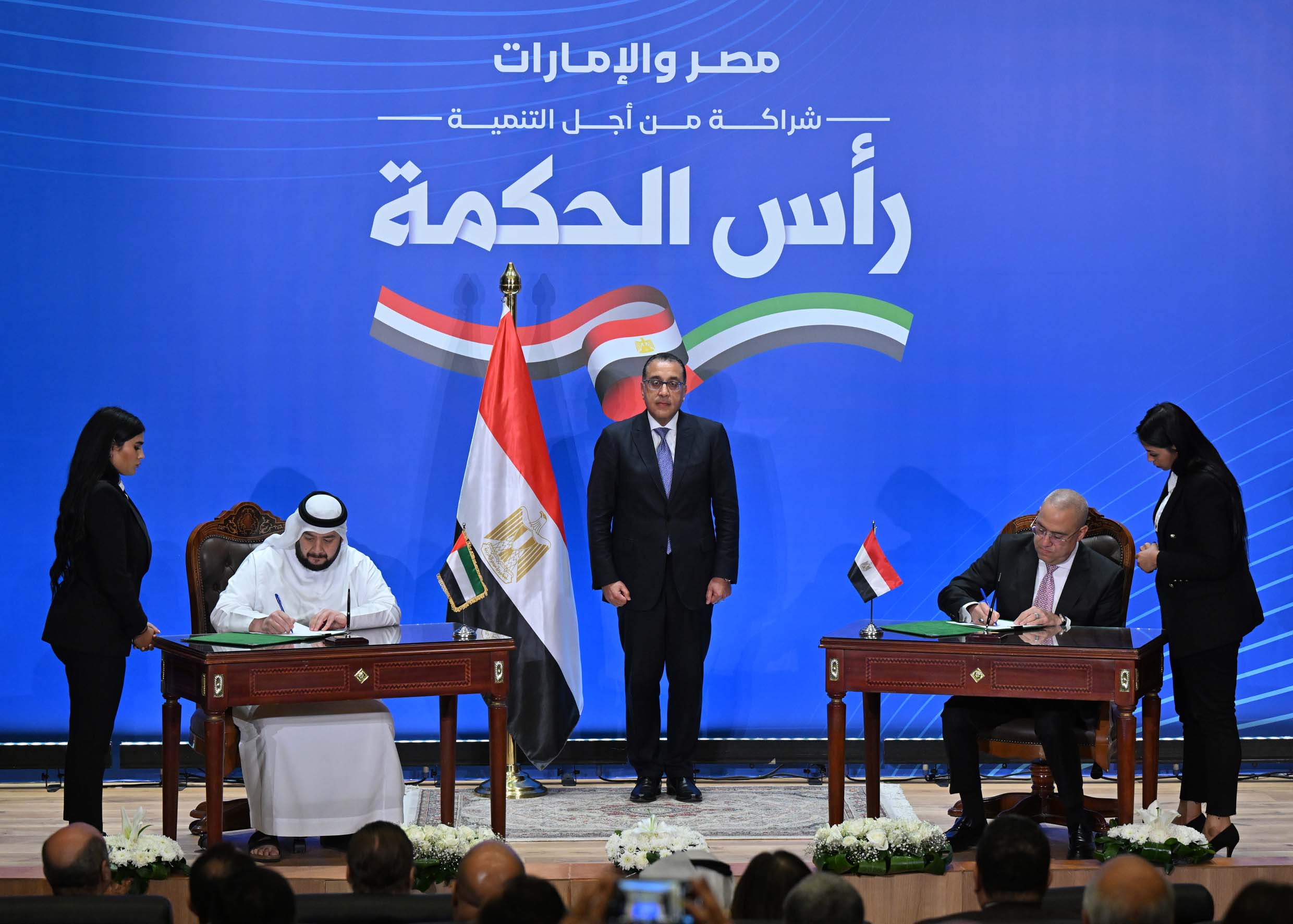

This time last year, the central bank’s overnight deposit rate was 18.25% – it is now 27.25%. The Egyptian pound’s official exchange rate to the US dollar was then just over E£30 – it is now almost E£50. But such is the price of economic salvation. A long-expected currency devaluation on March 6th opened the doors to an expanded IMF programme that will provide another $8 billion. Less than two weeks earlier, Egyptian prime minister Mostafa Madbouly announced a $35 billion deal with the UAE, $29 billion of which is for the development of Ras al-Hikma on the Mediterranean coast.

Rich Gulf states like the UAE that are prepared to keep providing financial support are just as keen as the IMF to see Egypt make good on promises of structural reform. Like the IMF, they are also increasingly willing to make investments contingent on proof of progress. Egypt’s officials are keen to signal their commitment to long-term reform, knowing the country’s future depends on it.

In an Atlantic Council interview in late April, central bank deputy governor Rami Aboulnaga was clear that going forward it will be the market that determines the Egyptian pound’s value. “Whether it’s fair or not will only be set by the market and the market dynamics,” he said.

Similarly, the government’s promise of reforms to kick-start private sector growth are not, Aboulnaga emphasised, a set of one-off policy measures. “This is a change in paradigm and I think this is here to last,” he said.

A stressful symbiosis

The health of a country’s banking sector is always tied at least in part to that of the sovereign and the public sector. But among their emerging market peers, Egyptian banks stand out for their high exposure.

Back in 2018, S&P Global Ratings estimated sovereign exposure accounted for around 55% of total banking assets. By the end of 2023, that figure had reached 60%. Fitch estimated that total exposure to the sovereign and broader public sector was almost 75% of total banking assets at the end of 2022 – or around 11 times banks’ equity.

“This is one of the cases where we have an extremely strong correlation between sovereign risk and banking risk because exposure to the sovereign is extremely high,” says Regina Argenio, a senior analyst in S&P Global Ratings’ financial services team.

The immediate benefit to the banks of the UAE and IMF agreements, therefore, is that the ship of state to which they are tied looks far less likely to sink. FDI, a liberalised exchange rate and ambitious budgetary consolidation targets, lay the foundation for growth and debt stability, according to S&P Ratings, which promptly changed its outlook on the sovereign to positive.

A second boon for the banks is that unifying the official and black market exchange rates has helped clear a massive and unmet demand for dollars. Quantifying the scale of this demand is not straightforward. Some analysts suggest excess liquidity in the Egyptian pound is a solid proxy for dollar shortages. Firms that would typically change pounds into dollars to pay for imports struggle to source dollars, and have nowhere else to put them but the banking sector.

If you’d asked me a few months ago, I would have said the dollar shortage would take six months to resolve. We cleared our entire outstanding demand for dollars in six days.

Todd Wilcox, CEO of HSBC Egypt.

In the weeks before the currency devaluation, central bank auctions for one week fixed-rate pound-denominated deposits were almost nine times oversubscribed. But when the long-awaited revaluation arrived the shortage disappeared with unexpected speed. The central bank injected dollars through the state-owned banks, and hot money investors sold dollars to the banks in the wake of the exchange rate cut.

“If you’d asked me a few months ago, I would have said the dollar shortage would take six months to resolve,” says Todd Wilcox, CEO of HSBC Egypt. “We cleared our entire outstanding demand for dollars in six days.”

Wilcox says around 60% of the outstanding FX requests were met. Much of the remaining demand simply disappeared as the exchange rate corrected. “When the Egyptian pound hit 48 to the US dollar, investors started to take interest in the domestic currency again,” he says.

The Ras al-Hikma announcement changed everything, say bankers. The deal injected a huge amount of confidence back into the market, which has started to bring retail investors and their dollars back to the banking sector.

Although the short-term demand for dollars has been sated, there is a longer term issue. Banks had to use their FX liquidity to support the government and central bank as foreign investors left. Foreign assets have declined, while foreign liabilities have increased. The result is that Egyptian banks’ negative net foreign asset position reached a record -$16.2bn in December 2023, according to BMI research.

This is going to take a while to redress, but the devaluation is a solid first step. Analysts expect it will make Egyptian companies in receipt of foreign currency earnings more likely to place those with the banking sector. Tourism remains a major earner for Egypt. Despite the war in Gaza and growing geopolitical volatility, foreign visitor numbers have held up well. Suez canal receipts – another vital source of FX – have fallen in wake of attacks on shipping by Yemeni militants. But they are still well above the pandemic lows.

“Most of those monies should eventually be channelled into the banking sector, which in turn will help reduce the sector’s net external liability position,” says Argenio.

The return of remittances would be another shot in the arm for the economy and the banking sector. Money from Egyptians working abroad is a key source of foreign currency, and one that plunged as the gap between the official and bank market exchange rates widened in 2023. Remittances in 2023 are likely to have fallen 15% to $24.2 billion, according to World Bank projections.

“That’s what we’re watching for now although we’re still at the early stages of adjustment,” says Wilcox. “Remittances accounted for a huge amount of foreign currency and I think it will come back, but it might take longer.”

Devaluation rattles ratios

The massive shifts in currency and interest rates is also rippling through to risk weighted assets (RWA) and capital ratios. Despite the negative net foreign asset position, a decent chunk of banking sector assets are still in FX. S&P Global estimates that about 19% of assets were in foreign currency as of October 2023.

The devaluation of the pound – which fell almost 40% when the government announced a market determined exchange rate in early March – has increased the value of those RWA in local currency terms. Following the announcement, S&P estimated that a market determined exchange rate could consume 300bp-400bp of banks’ total capital ratios, depending on their balance-sheet structure.

But for the banks that S&P covers adjustment should be manageable, says Argenio. In fact, across the sector high regulatory capital ratios mean lenders should have sufficient buffers to absorb the hit. This is not luck.

Egyptians banks are – almost across the board – well run, well capitalised and protected against risk. Egyptian lenders cannot lend more than 50% of the acquisition for a leveraged buyout. They cannot trade in derivatives. They cannot take speculative positions on FX.

This new interest rate environment might be hard for some borrowers to manage, particularly the SMEs who might struggle to refinance at this new level

Regina Argenio, senior analyst, S&P Global Ratings’ financial services team.

For borrowers, the devaluation has increased the amount of money that they will have to repay to the banks. This will be particularly hard for borrowers without a natural hedge. But it is unlikely to be ruinous for many firms. When it comes to corporate lending, banks mainly lend to exporters who earn revenue in foreign currency. The rest of the FX lending is to the sovereign.

A bigger issue for borrowers – and by extension banks’ asset quality – is the hike in interest rates. The IMF package comes alongside a 600bp hike in interest rates, on top of the 200bp hike earlier in the year and the hikes in 2023. The central bank’s overnight deposit rate has risen from 9.25% to 27.25% in less than two years. This is almost certainly going to cause problems for borrowers – the question is to what extent this feeds through into loan quality,

“This new interest rate environment might be hard for some borrowers to manage, particularly the SMEs who might struggle to refinance at this new level,” says Argenio. “Economic growth has been sluggish over the past year, so they might not have much in the way of cash reserves.” The hope is that this kind of struggle will be relatively short lived as FDI and reform improves medium-term economic growth and stability.

But so far there has been little sign of anything problematic in loan portfolios. Wilcox says he views retail banking as the canary in the coal mine. “If you start seeing the credit card default edge up, that’s when there’s an issue,” he says. “There’s been no change whatsoever in our credit card portfolio, it’s one of the cleanest I’ve seen. The banking sector here is very, very resilient.”

Ending the cycle

Profits bear that statement out. Total banking sector net profit more than doubled in 2023 to E£283.4 billion ($5.9 billion at current exchange rates). All of the main Egyptian banks have approved dividend payments for the 2023 financial year. If in some cases the dividends are perhaps a little smaller than in previous years, this is mostly banks being prudent in using healthy earnings to strengthen their capital base. No-one expects sticky inflation, asset repricing and higher deposit rates to really dent profitability.

“Banks have managed partly because of very good systems and good quality people running the banks,” says Angus Blair, the CEO of the Cairo-based Signet Institute. “Institutions become much better over time when faced with crises because they can anticipate and know what to do based on experience.”

The question then turns inevitably to the future, and whether this time really is different. Or whether the next few years will bring only temporary respite before banks are forced to yet again face economic turmoil. The Egyptian authorities have promised a market-determined exchange rate, fiscal restraint, budget consolidation and – perhaps most importantly – an economic environment that allows the private sector to grow.

Banks have managed partly because of very good systems and good quality people running the banks. Institutions become much better over time when faced with crises because they can anticipate and know what to do based on experience.

Angus Blair, the CEO of the Cairo-based Signet Institute.

Mahmoud Bahaa, head of global markets & treasury at Emirates NBD Egypt, says the major shift in international investors’ confidence and the government’s commitment to create a more liberal and competitive market is a huge opportunity for Egypt. “It’s a path for the country to restore its position among the most competitive emerging market investment opportunities.”

Egyptian banks and businesses are dearly hoping the government follows this path. Stripping away needless bureaucracy would be a great start. A seemingly endless list of approvals for business activities has hampered the economy for years.

Analysts often point to the dominance of state and army-owned firms as a key factor behind the lack of competitive Egyptian exporters. But Tarek Abdel Rahman, managing partner, Compass Capital says that in fact there are parts of the private sector that could be far more competitive if freed from all the red tape.

“Chemicals is a big export business, as is agriculture and garments,” he says. “A lot of firms across the economy are looking to invest abroad or export because of the crisis.”

Ultimately, says Rahamn, what will improve the banking sector is a more vibrant private sector and increased living conditions for the majority of Egyptians. “Unless we have a significant change in economic policy, we have a honeymoon period of three, four or five years and then we end up in the same situation.”