Despite the pandemic and its deep economic impact, the $2 trillion core GCC banking sector will weather 2020-2021 intact and be poised to benefit significantly from acceleration in the economic diversification programmes implemented by the region’s governments. These programmes are authentic, and the coronavirus pandemic has given every country in the region very strong reasons to implement them more quickly than before. Within five years – almost certainly sooner – the GCC1 will have fewer, bigger, better banks and these banks will be more international, more digital and more customer focused.

Prior to the pandemic, the most recent pivot point for GCC banks was the oil price crash of 2014/2015. This slump precipitated a region-wide strategic drive to consolidate banks at a national level, to tighten lending processes, diversify income streams, upscale technology, launch new products and enter new markets. These trends will accelerate in 2021 and beyond.

The pandemic is having a negative effect on bank profitability and asset quality across the region but with the support of central banks and strong capital buffers going into the crisis, the region’s banks are stable and resilient enough to weather the dual storms of the pandemic and low oil prices.

Given the macroeconomic and structural challenge of the pandemic and the region-wide transition to more diversified economies, as well as sector-specific lending concentration concerns, organic growth over the next few years will be relatively muted.

Dubai started the trend (as it so often does) towards consolidation by merging Emirates Bank and National Bank of Dubai back in 2007, and also recently merged Dubai Islamic Bank with the smaller Noor Bank. Abu Dhabi increased the pace in 2016 by bringing together five banks into two national champions – First Abu Dhabi Bank (FAB) and ADCB.

Saudi, the region’s biggest economy by far, has joined in at scale, with a $220 billion merger between National Commercial Bank (NCB) and Samba Financial Group, slated to complete mid-2021. Kuwait Finance House (KFH) and Bahrain’s Ahli United Bank (AUB) are also set to unite to create a regional bank with more than $100 billion in assets should that transaction close, as planned, in 2021. Smaller markets, such as Oman, Qatar and Bahrain, have wed smaller, weaker institutions to larger, stronger ones and have great potential for further consolidation as profitability, digital disruption and cost-saving strategies come to the fore.

Given the macroeconomic and structural challenge of the pandemic and the region-wide transition to more diversified economies, as well as sector-specific lending concentration concerns, organic growth over the next few years will be relatively muted. Bank growth during this period will come mainly from further consolidation and the resultant cost and efficiency savings. At the individual bank level, profitability will be driven by a combination of good risk management, revenue diversification and the speed and success of transition to digital platform models.

Further into the future, the secular growth of the region’s banking sector is inextricably tied to the long-term success of the region’s diversification programmes. We believe that the region is very serious about the need to diversify and that the success of initiatives in Dubai, Abu Dhabi and particularly in Saudi Arabia will spur the region toward a more economically balanced model with a greater role for the private sector. As long as the region avoids pitfalls such as an overemphasis on sectors like construction and real estate, then the banking sector should profit alongside this diversification.

GCC banking to 2019

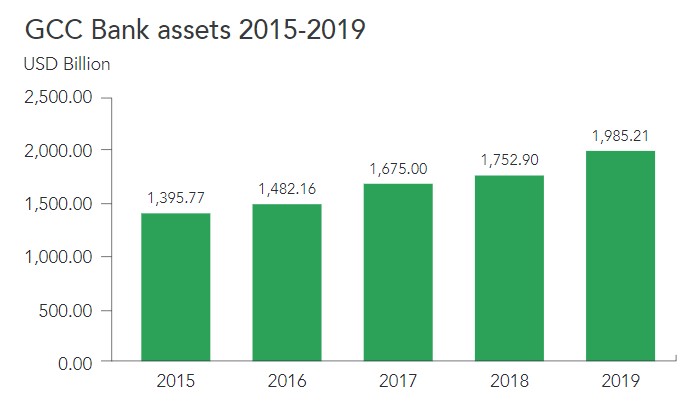

Despite the challenging macroeconomic environment in which it was operating, the banking sector in the GCC experienced a period of stable growth from 2015 to 2019. Assets held by our group of core GCC banks grew steadily each year, increasing by 70% in the five years to the end of 2019. In dollar terms, the overall sector grew from $1.4 trillion to $1.98 trillion in assets.

Assets per head of population in the GCC grew from $27,000 to $34,000, demonstrating how the region, and particularly Saudi, has become more banked over time.

Over the five years, the concentration of assets held in larger banks also became more marked. In 2014 there were only three banks with assets around or above $100 billion (Qatar National Bank (QNB), NCB and EmiratesNBD) – in 2019 there were seven, with two over $200 billion. Overall, in 2019 the top 10 GCC banks held 70% of the total core asset pool, against 60% in 2015.

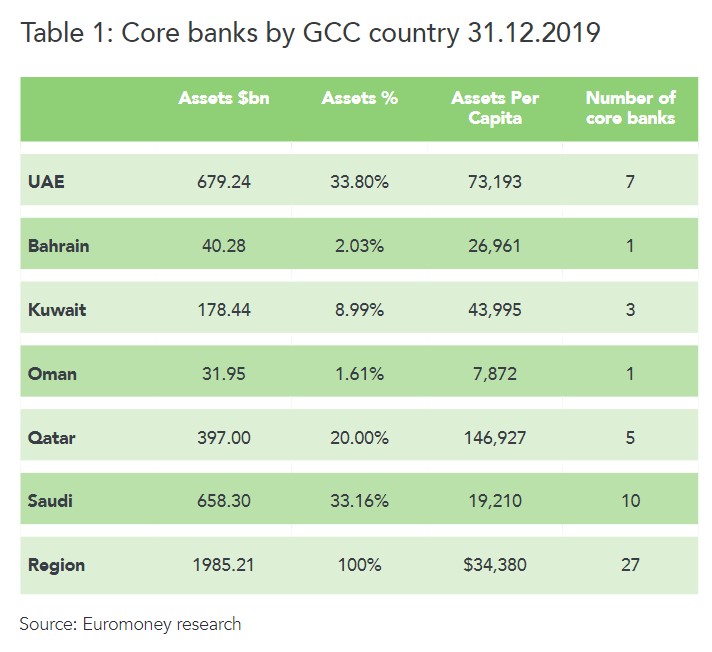

These assets were evenly spread between the region.

Despite all the GCC economies being more or less based upon the same economic model and sharing similar cultures, the region’s banking sector is anything but homogenous. Saudi Arabia makes up around 60% of the region’s population and has more than 50% of the region’s GDP but less than 34% of the region’s banking assets. Qatar, at the other end of the scale, has only 4.5% of the region’s people but 20% of the region’s bank assets. And yet only Bahrain and Dubai could make a claim at being the region’s financial hubs.

In 2015, about 24% of assets were in purely Islamic banks, 40% in hybrid banks and 36% in conventional banks. By 2019 this had shifted slightly in favour of hybrid banks, particularly in Saudi, which held 45% of total assets in hybrid banks, with pure-play Islamic banks dipping to 21% of the total.

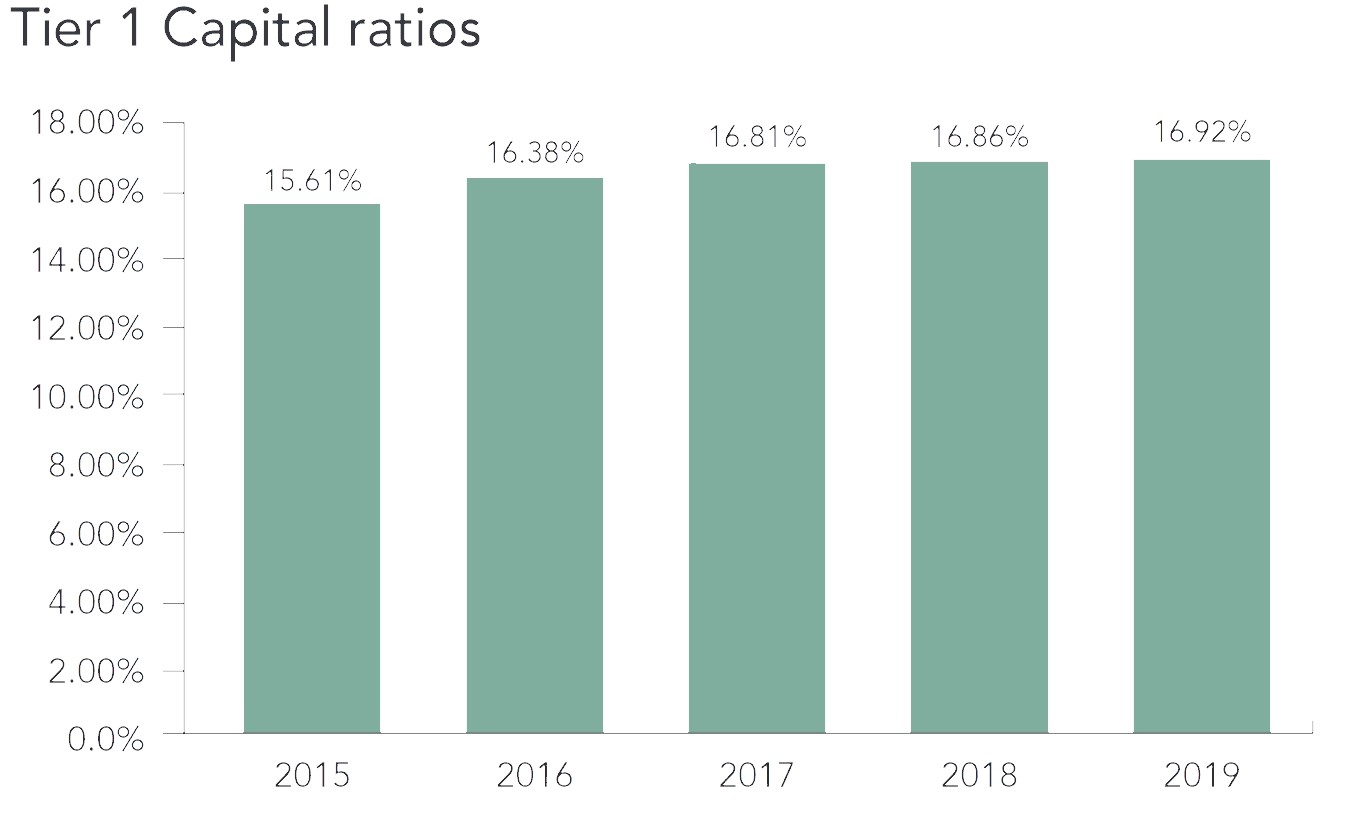

Banks in the GCC became safer between 2015 and 2019. Common equity tier 1 (CET1) improved from 15.61% in 2015 to 16.92% in 2019 and capital to risk-weighted assets from 17.16% to 18.26%.

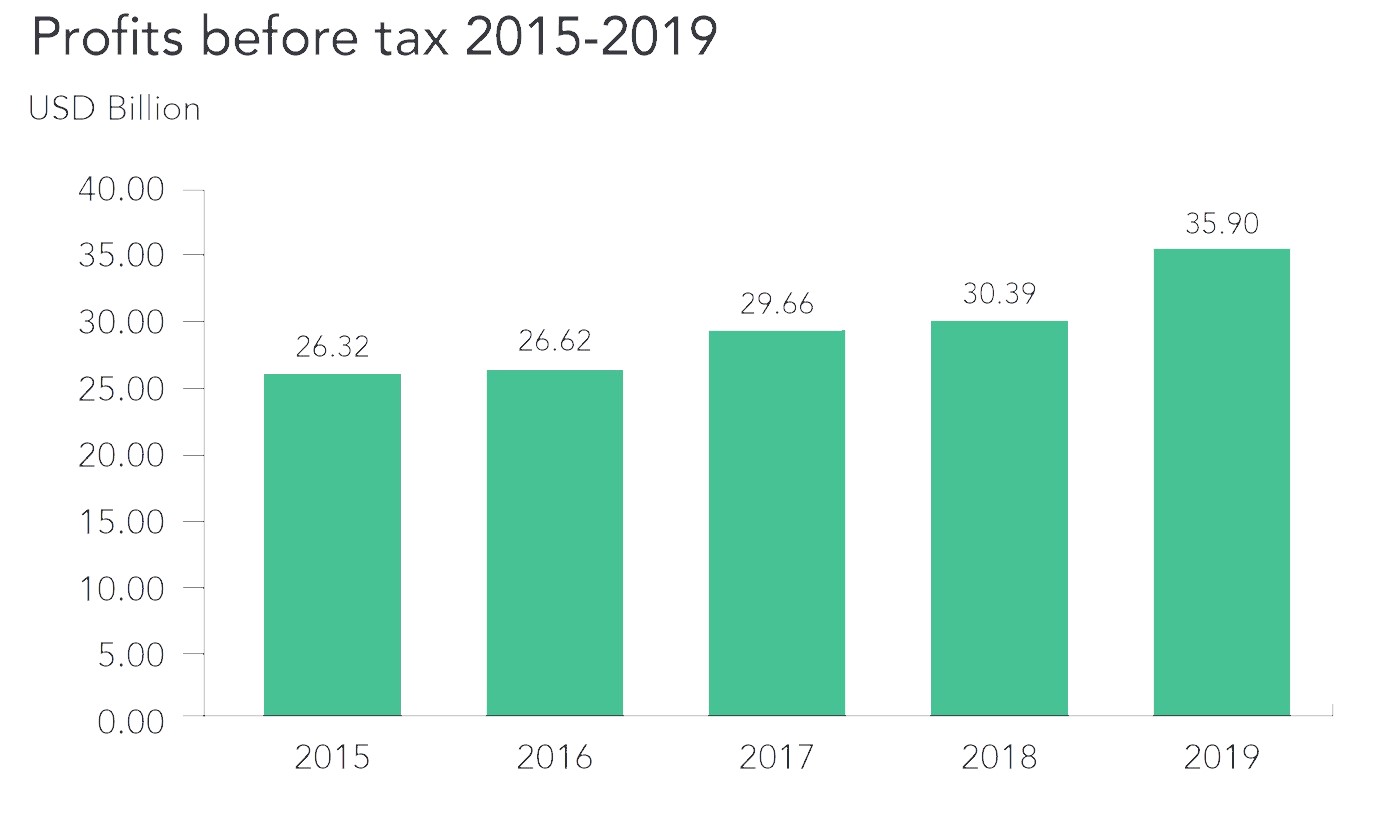

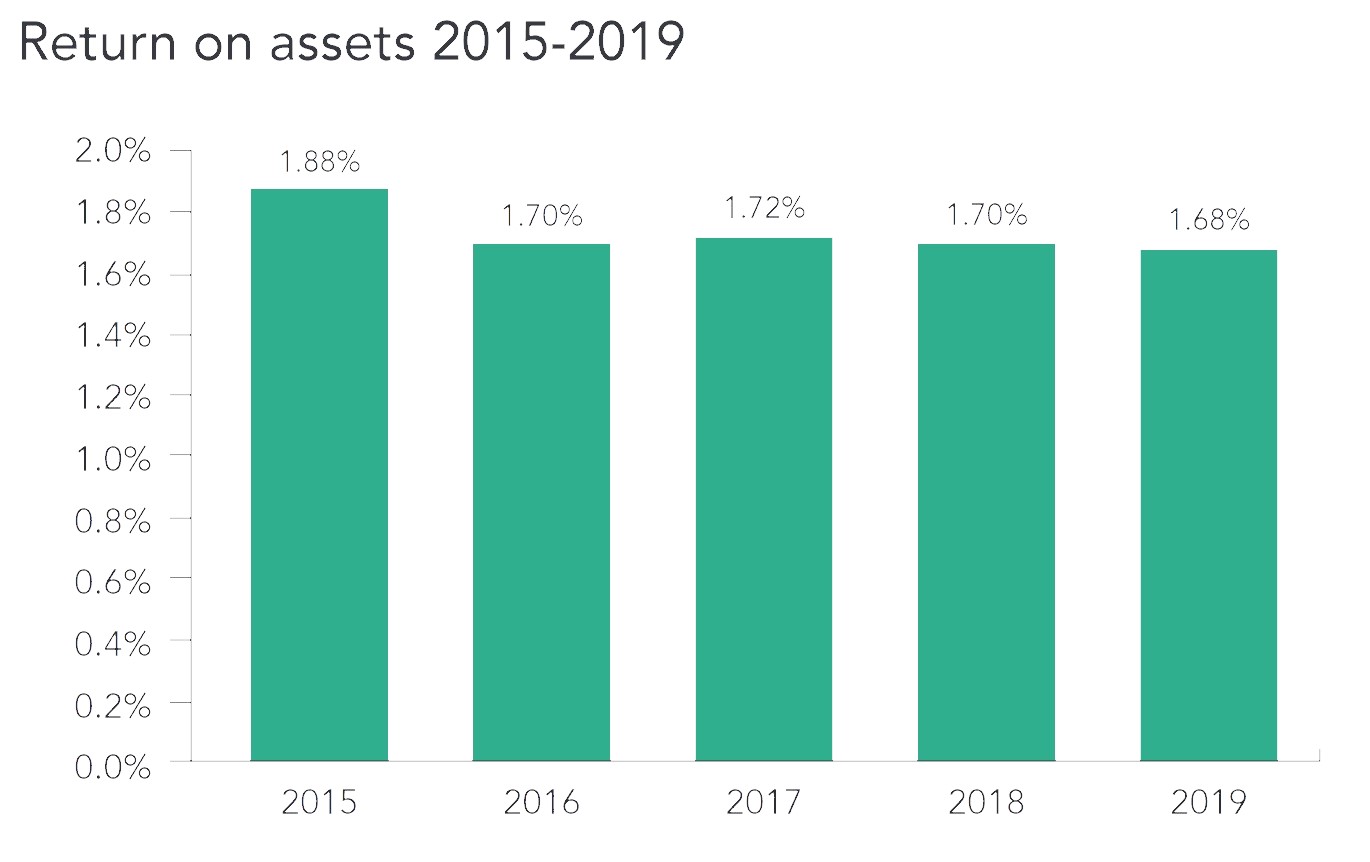

Profits grew too, but by less than asset growth. Total pre-tax profits for the sector in 2015 were $26.3 billion compared to $35.9 billion in 2019. This gave the sector a return on assets of 1.88% in 2015 and 1.68% in 2019. Return on equity has, perhaps inevitably, fallen slightly – from 13.7% in 2015 to 12.2% at the end of 2019– but remains good when benchmarked globally.

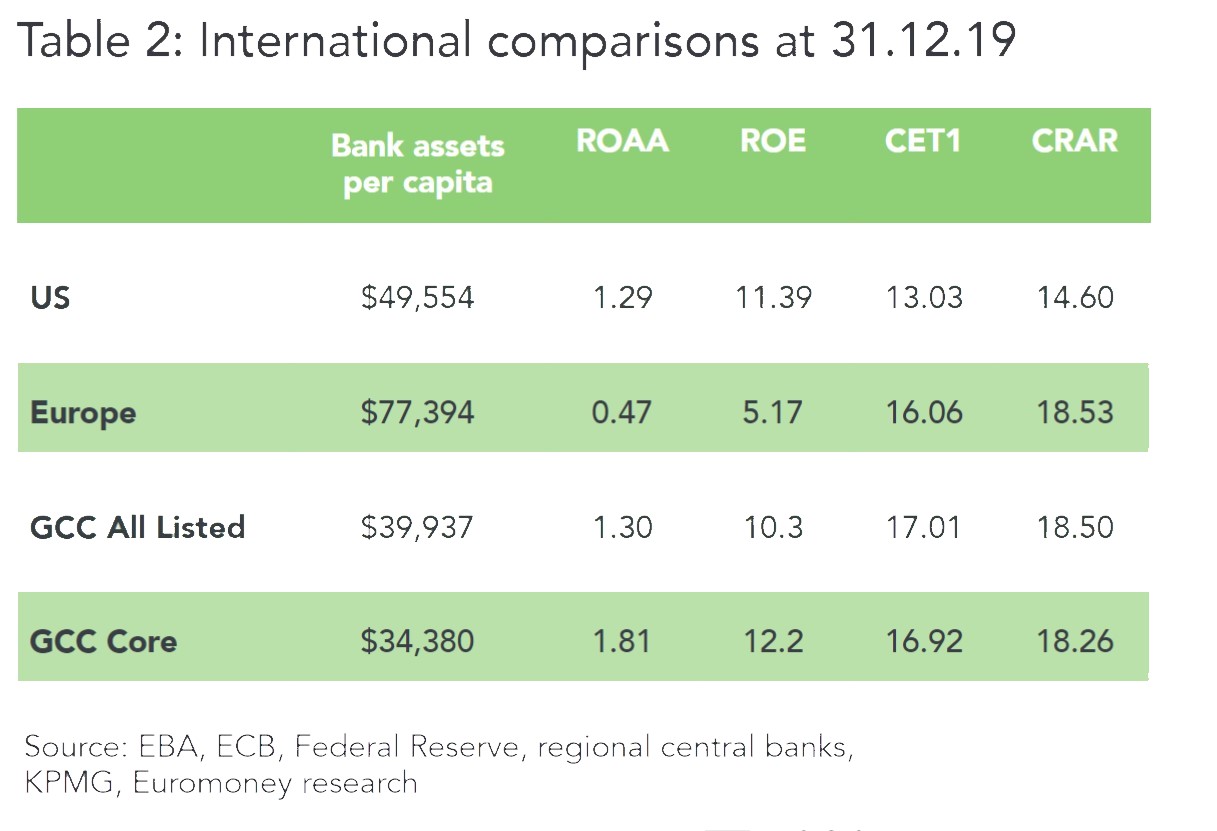

Comparing size and performance across different regions also gives interesting perspectives on the core GCC banking sector. It is, naturally, small compared with the US and the EU. The US had commercial banking assets of some $17 trillion in 2019 and the EU around €34 trillion in all the credit institutions headquartered in the union. That makes them nearly 10 and 20 times the size of the GCC banking sector respectively. This is unsurprising given the population differentials, but both regions are marginally more ‘banked’ than the GCC, showing there is some growth potential for the GCC banking market. It would need to double in size at constant population levels to reach the same level of bank assets per head as the EU.

The profitability and capital buffers of the GCC core banking sector also compare favourably with the US and the EU. Banks in the GCC are, on average, more profitable and have more capital relative to their assets than their counterparts in the west.

GCC banking in 2020

2020 is shaping up to be an annus horribilis for the GCC economies. But what will the impact be on its core banks and what are the banks and governments doing about it?

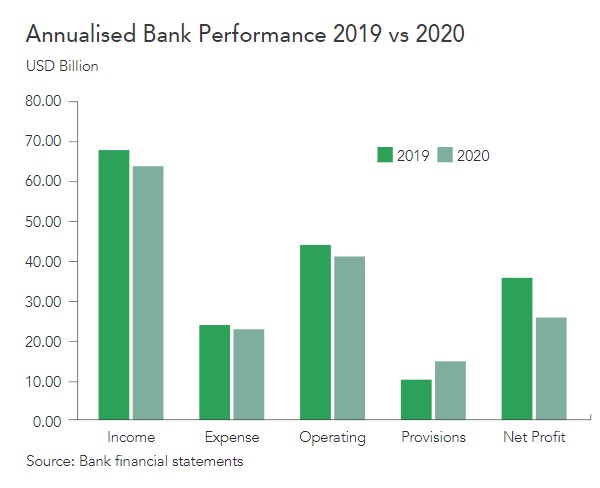

Based upon the financial statements for our bank universe for the first half of 2020 and comparing them on an annualized basis we see that, unsurprisingly, both income and expenses are down, and provisions have risen by nearly 50%.

This is a crude estimate, we accept, but it shows the direction of travel clearly. It also shows that the sector remains profitable and is not in systemic crisis. Across our core banks, CET1 is down from 16.92% on 31/12/19 to 15.92% on 30/06/20 – but is still well above the nationally mandated capital minima and objectively strong.

We believe that the second half of 2020 will be generally tougher than the first but not by a large degree. The performance of the sector will be driven, to a large extent, by how quickly the support initiatives of regulators and governments are reduced or withdrawn completely.

The full effect of the pandemic on the region’s banks has yet to be felt, as swift and extensive central bank action has provided a supportive bridge in 2020. Most of the region’s central banks have not formally extended their support programmes beyond the third quarter of 2020, but we believe that they must – and will – as some stress is showing in the real economy, particularly in sectors such as real estate and construction.

The region’s banks are stable and liquid, but there will inevitably be asset quality deterioration across the region and, combined with a lower-for-longer interest rate environment, profitability will be impacted meaningfully in every bank. This has been reflected in the combined market capitalization of the sector, which has trended downward from $409 billion to $332 billion since the start of 2020.

Credit ratings for the sector tend to track the rating of the sovereign entity in which each bank is located and most of the rated banks are on one form of credit watch or other. Future ratings actions on banks will be driven by ratings actions on the sovereigns.

The next two years will be a difficult time for GCC banks to increase significantly their profits and overall performance, but they will remain resilient, stable and profitable. Returns on assets will be only marginally below their historical trend line (1.1%-1.2%), and capital buffers will remain in excess of national minima and international benchmarks. The region’s banks and their regulators learned well the lessons of 2008 and 2014.

The future of GCC banking

Post-pandemic, the nations and banks of the GCC will prosper in the medium to long term based upon how successful they are at diversifying and reforming their economies and business models. Hydrocarbon-based income will form an outsized part of the region’s economies for decades to come but true growth and real sustainability will only be achieved by moving away permanently from the models that have prevailed since 1950. Which is why all governments in the region have re-committed to extensive reform programmes. These transition and development programmes are reflected at the bank level too.

Organizational efficiency – more mergers

As noted above, the banking sector of the GCC remains relatively unconcentrated. There is plenty of room for further consolidation and the development of more national champions.

At the time of writing there are two large mergers under negotiation: National Commercial Bank (also known as Al-Ahli Bank) and Samba in Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait Finance House with Ahli United Bank in Kuwait/Bahrain. Also under discussion is the merger of Masraf Al-Rayan Bank and Al-Khaliji bank in Qatar.

The NCB/Samba tie-up would create the largest bank in Saudi Arabia and the third largest in the region by assets. KFH/AUB would create a truly regional bank with assets of more than $100 billion. So far, the UAE banking sector remains split between Abu Dhabi and Dubai banks – each with a strong footprint in, and degree of ownership by, the government of their home Emirate. In the future, a logical step could be to create a truly pan-Emirates banking group, which would likely be the largest in the region.

What is also likely is that mid-tier banks (assets from $20-50 billion) see the benefits in joining to create larger, more efficient institutions. The ties that bind banks to particular cities or merchant families still remain but are loosening and we believe that further consolidation will make increasing sense, as lower revenue growth continues to shift management and shareholder focus to cost reduction and efficiency.

Digital acceleration and the emergence of banking platforms

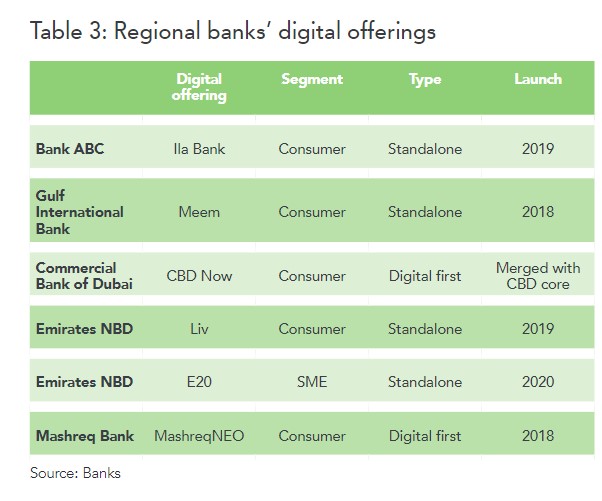

Since 2015, all of the banks in our universe have developed digital products, channels and services for their clients. The emphasis has been upon retail banking – with digital-only offerings complementing digital access to core banking products. Some regional banks have gone further and launched dedicated digital sub-brands (see table 3); but as of writing there are no true neo banks in the region.2

Before the pandemic, the young, mobile, connected population of the region had been quick to adopt digital retail banking, but other segments of the market had been much slower. Cash remained important to older generations and to expatriates and trust/verification issues meant that cash was used in nearly 80% of online transactions in both Saudi Arabia and the UAE in 2018 – cash on delivery being the preferred payment method for online purchases pre-pandemic3. SME business, corporate and even public sector banking still remained largely analogue in critical areas such as accounting integration and payment/transaction approvals.

Some banks did develop more integrated digital solutions for their business customers. The UAE’s Mashreq Bank launched its MashreqMatrix platform in 2018 and in 2019 EmiratesNBD introduced its SmartTrade portal – both of which are aimed at transaction banking clients. Having these platforms already in place when the pandemic hit has served these banks and their clients well. Mashreq is a consistent innovator; it announced a tie-up with the Dubai International Financial Centre in March 2020 to offer a blockchain-based KYC (know your customer) platform designed to enable businesses new to the UAE to open accounts entirely digitally.

Consultancy Frost & Sullivan predict that GCC business-to-business e-commerce will grow by 234% in the next decade.

Digital usage rates have surged in 2020 and some commentators estimate that digital-only customer transactions have reached as much as 75% across the region – up from around 55% in 2019. The longest lasting effect of the pandemic (we hope) will be that it has proven to GCC customers, banks and regulators that the future of banking is digital.

Consultancy Frost & Sullivan predict that GCC business-to-business e-commerce will grow by 234% in the next decade. As is often the case with the GCC forecasts, we must allow room for caution. Many of the banks are talking a digital-first game but are yet to walk that talk. Legacy systems, regulatory hurdles, internal cultural blockages and more are slowing some banks’ migration to digital.

But there are others already on the journey towards becoming true digital banking platforms using open banking application programming interfaces (APIs) to integrate bank offerings into corporate client systems to provide clients with live views of their cash and working capital positions, anticipated cash flows and investment performance. By linking these API dashboards with data mining using artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML), and using a combination of automated and expert human analysis, these banks are already offering superior products and services directly to their customers as well as reducing both their own and their customers’ costs through optimization of netting and real-time pricing.

It is these institutions that will benefit significantly from the accelerated digital migration brought on by both the pandemic and the changing strategic direction of the GCC.

We do not, however, see the region as particularly attractive for independent neo banks or digital challengers. The GCC’s geographically fragmented nature – five small countries and one medium-sized one – does not easily provide scale to international banks, and the regulatory burden of dealing with six separate regulators for a total market smaller than Canada is de facto prohibitive.

The drive by regional governments to localize employment and develop their own private sectors also is not encouraging for international digital players that require, by law, local regulation. We do not believe that there is much prospect for external financial or fintech disruptors significantly to enter the sector in the next decade.

The application of fintech and any ensuing disruption of existing business models is likely to come from incumbent banks in partnership with strong international partners or from local technology players. Saudi Telecom (STC), for example, has launched STC Pay, a mobile wallet allowing transfer of money between its customers and to banks. Big local telecom/technology players such as Etisalat in the UAE or Zain in Saudi and Kuwait are also looking to offer some financial services products to their customers. Mobile wallets are particularly a focus. However, these firms often have similar shareholders (both public and private) to the banks with whom they are competing and we believe that large scale disintermediation of incumbent banks remains less likely than some commentators and promoters believe.

Business diversification and growth

For GCC banks, the main opportunities for business diversification will come from the opening of new geographic markets outside the GCC; the design of new products; and the creation of tightly defined customer-focused business segments.

With the exception of some segments of the Saudi market (see below), competition for customers in the GCC is high. That is less true, however, in the wider MENA+ region. There is substantial opportunity to acquire new customers in regional markets such as Egypt, Iraq, the Levant and further afield in Turkey, Pakistan and east Africa (Sudan particularly). Additionally, in many of these markets there is some linguistic similarity and cultural affinity with the GCC.

These MENA+ countries have young populations which provide genuine medium to long-term growth opportunities and, by 2030, could have a combined population of some 500 million – more than 10 times that of the GCC itself.

A considerable number of GCC core banks are already in these markets – for example, FAB, EmiratesNBD, AUB, QNB, MashreqBank and National Bank of Kuwait operate in Egypt, KFH in Turkey, Al-Rajhi in Jordan and AUB in Iraq and Libya. These wider regions’ markets each come with their own challenges but are familiar to the GCC banks that frequently serve corporate clients who operate extensively in those markets already.

Israel is a surprising new market for some GCC banks which has emerged in 2020. On 13 August the UAE and Israel signed a normalization agreement, grandly called the ‘Abraham Accord’. Bahrain followed suit in September. Very soon after, a delegation of Israeli banks visited the UAE and announced the intention to establish cooperation with Emirati banks.

The GCC is situated between India and Africa, two large markets that are forecast to grow structurally throughout the next decade and beyond, and the region intends to capitalize on its position. Qatar’s Doha Bank has a full subsidiary, Doha India, already operating on the sub-continent, for example, as does Abu Dhabi’s FAB, and India is set to be a key market for growth in the next 20 years. China and wider Asia are two other important growing trade corridors for the GCC. Abu Dhabi and Dubai are both planning to significantly grow their business as trading and financial hubs in these regions.

In addition to new markets, there is also growth to be found from the development of new products, services and platforms for regional and global customers.

Transaction banking is one such area. GCC banks can potentially increase transaction banking revenue by 20%-30% across business lines including cash management and trade services. However, there is plenty of competition from other local, regional and global players and margins are tight. This means that it is essential for GCC banks either to find scale or to develop highly specialized niches that can command fee premia.

The economic reform plans of the GCC governments all require significant growth in the private sector and will translate primarily into growth in the SME sector, specifically medium-sized enterprises. There is a hugely vibrant start-up scene right across the GCC from which there have already been some notable exits, such as Careem’s sale to Uber in 2019 for $3.1 billion.

The Saudi housing market is another interesting source of secular growth. With a population of more than 30 million, less than half a million mortgages in the market and more than 1.2 million new homes planned to be built by 2030, Al Rajhi Capital estimates the Saudi mortgage market could be worth up to $100 billion for Saudi and Saudi-registered banks by the end of the decade.

Other opportunities will come in business lines such as wealth management. The region’s middle class will increasingly look towards supplementing their possibly less generous state pensions with individual retirement and savings products.

Conclusion – 2021 and beyond?

Only the most Panglossian of analysts could claim that the future of GCC banking is free of challenges, but when today’s storm clouds have passed, which they will, the sector should be poised to generate significant and sustainable growth.

Much depends, of course, upon the success of the region’s economic diversification programmes. There will be leaders and there will be laggards but, for those banks who can use this period of trial to concentrate their businesses, mindsets and people on a flexible, customer-focused and digital-first future banking model, there is every reason to believe that they will succeed in their journey.