|

The inability of Italy’s banks, government and judicial system to grapple with the fallout from years of recession and decades of low growth has spawned a nightmare vision. In it are legions of aging unionized employees in drab branches on down-and-out high streets. Above them, layer upon layer of senior managers and directors hanging on: years after mergers rendered them superfluous, they’re doing nothing to manage the billions of dead loans that make up their balance sheets.

More mergers between banks could help dispel this vision, particularly among Italy’s swathes of small and medium-sized mutual lenders. The merger between Banco Popolare and Banca Popolare di Milano (BPM), planned to complete by year-end, offers some hope that the crisis in Italian banking, together with the 2015 reform of the popolari (cooperative bank) sector, could really lead to consolidation.

“The only answer – to a lower interest-rate environment, pressure and burdens from regulators, and the need for big digital investments – is to consolidate,” says Giuseppe Castagna, BPM’s chief executive, who is also set to become CEO of the combined entity.

The fit between the two banks is almost perfect - Maurizio Faroni, Banco Popolare

If the merger proceeds as expected after the banks’ extraordinary general meetings in October, the new entity, Banco BPM, will be Italy’s third-biggest bank by market capitalization. It will have an asset base of €171 billion. The merger will coincide, too, with a transformation to joint stock, which will in any case be obligatory by year-end for all the biggest popolari.

“I think it’s the start of something, for sure,” says Luigi de Vecchi, chairman of continental European corporate and investment banking at Citi, which advised BPM with Lazard (Bank of America Merrill Lynch and Mediobanca advised the other side). “There could be a number of other transactions that are being contemplated. The other banks are reviewing their options after this deal.”

If de Vecchi is right, this could be encouraging news, as better efficiency and profit through synergies might help banks afford to write off more of their hundreds of billions of euros of bad debts – and allow them to leave the job of putting zombie companies out of their misery to specialist NPL managers, eventually freeing up banking resources for new lending.

BPM and Banco (as Banco Popolare is known) say synergies in costs, funding and revenues from the merger will amount to €365 million a year, helping bring the combined cost-to-income ratio below 60% and increase return on equity from 5.5% to 9% over the next three years.

|

Maurizio Faroni, |

“The fit between the two banks is almost perfect,” says Maurizio Faroni, Banco’s general manager, who is set to become Castagna’s number two.

“The merged bank will cover in a very widespread way the northern part of the country, the most industrialised regions,” says Faroni. “It can create a player that has the opportunity to be a market leader in retail and mid-cap clients, private banking and asset management. It is a way to differentiate the revenue stream and create a more resilient group, in an environment of low and negative rates.”

Banco’s size, according to Castagna, was a main reason why it was more attractive to BPM than other potential merger partners, despite its relatively high NPL ratio of around 25% (one of the highest in the country), to BPM’s 16%.

“We wanted really to change the category and not be one of the many regional banks but one of the most important national banks,” says Castagna. “If we would have gone with a smaller bank, then this wouldn’t have happened.”

Overlaps will allow the merged entity to close 350 branches, with a similar number slated for closure as part of the shift to digital channels. But Castagna says there is very little overlap of clients, with overall numbers set to grow to 4 million in the merger, while the banks’ geographic strengths are very complimentary, particularly in Lombardy (the region around Milan), where it should have a dominant position after the merger.

“With Banco, we will be the biggest bank in Lombardy, bigger than Intesa Sanpaolo; 80% of our assets will be in the north of Italy,” says Castagna.

Cold water

But despite all the fanfare when the merger was announced in March, the ECB immediately threw cold water on any excitement by demanding, according to Faroni, a €1 billion capital increase by Banco (which it completed in June) before the deal could go ahead. It was hardly an encouraging sign for Italian bank consolidation hopes, given this was the first big merger the European banking union has overseen.

The bankers involved in the process suggest the ECB’s thinking was that a more systemically important bank needs a higher capital ratio. The extra capital will allow Banco to increase bad-debt coverage from 37% to 41%, according to Berenberg. It managed to mitigate the dilution, according to Faroni, by increasing the terms of exchange for its shareholders (Banco shareholders will get 54% of the merged entity).

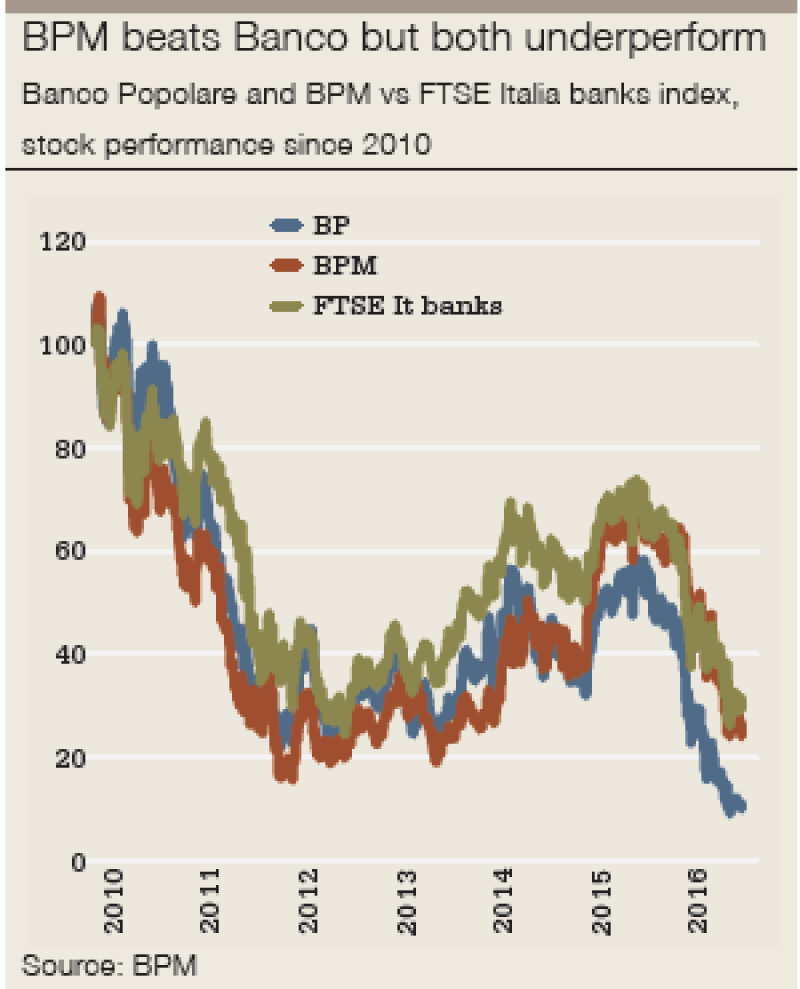

But as it coincided with news of the imminent capital increase, stock in both banks plummeted when the planned deal was announced. Shares had rallied when rumours of the merger first appeared in January – and when they announced a joint strategic plan in May. The capital increase came as a surprise, not least as the market expected the ECB to be more supportive of mergers, given the need for cost savings, not to use it as another cause to get banks to bump up capital ratios.

Both banks had passed the ECB’s stress tests six months earlier. “We entered into discussions with BPM with a large margin, about 300 basis points, over our minimum regulatory capital requirement,” says Faroni. “We were entering into an M&A combination where the cost savings, synergies and the value creation was clear and easy to demonstrate. This was the best assurance of the quality of the new company and the capacity to maintain the capital buffer.”

Castagna maintains that more mergers within the popolari sector will inevitably happen as the banks switch to joint-stock status. Particularly after Banco’s capital increase (even if largely used for provisioning), the institution he will lead could also take part in further consolidation.

|

Giuseppe Castagna, |

For the moment, the priority is the integration of Banco and BPM. But he says a merger could be possible in years to come with Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS), for example, if it succeeds in its plan to raise capital and offload NPLs – or at least with smaller cooperatives. “Maybe we can be also a consolidator in the future,” says Castagna. “Some regional banks could be willing to be aggregated into a model for cooperative banks which already has proved to be successful.”

Nevertheless, Castagna agrees that the ECB’s stance on his bank’s plan has stalled talks on other mergers that could otherwise be happening, if not be being finalized. “What really stopped further consolidation up to now may have been the ECB’s behaviour, asking for more capital,” he says. “I think that everybody will wait for next year to understand better what the ECB wants, how the market reacts to the need for more provisions and so on, before they would decide.”

Banco Popolare dell’Emilia Romagna (BPER), previously in talks with BPM on a merger, is no longer in any merger discussions, according to CEO Alessandro Vandelli. He says Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca, both rescued by the Atlante fund earlier this year, could offer an opportunity to expand in a wealthy part of the country (near Venice) – but not until they have offloaded NPLs.

The ECB’s stance on the Banco/BPM deal has complicated matters, according to Vandelli. “M&A is no longer as simple as looking at the capital ratios of your own bank and the potential merger partner,” he says.

Castagna might now have more of a head start over firms like BPER and UBI Banca. “We are very happy because we can be ahead of the others by a year, a year and a half – progressing and getting good results.”

But even if the merger goes ahead – and if others follow – it is not automatic that it will bring improvements for either the banks or the system, which was perhaps what the ECB had in mind too when it asked for new capital. Naturally, stronger banks take over weaker banks (often, in Italy, northern banks rescuing southern ones). This can cause the asset quality of the acquirer to deteriorate.

Cooperative banks are very much linked to the territory, to local constituencies. Not everybody is willing to lose their territorial grip - Giuseppe Castagna

In this case, BPM has done much to turn around and refocus its lending to healthier activities (including less real estate lending) since the Bank of Italy changed management and imposed capital add-ons in 2011 after launching an investigation into the bank’s governance. The nadir was the 2012 house arrest of former chairman Massimo Ponzellini in connection with an investigation into loans granted by the bank. Ponzellini has denied any wrongdoing.

Less than three years ago, it would have been much harder for BPM to contemplate a merger with Banco on an equal footing, given it was a third of Banco’s size by market capitalization, compared with almost half in early 2016. After losses in the range of €500 million in both 2011 and 2012, BPM regained profitability in 2013 and is now one of Italy’s better valued banks.

Castagna says he has built bridges with employees and refocused on the business since his arrival in 2014, after a confrontational initial battle under his predecessor to change the top-line management and governance, following Ponzellini’s departure. He says he had a similar experience with Banco di Napolo after its acquisition by Intesa Sanpaolo, where he later became head of the retail division at national level.

“We had the opportunity to have our turnaround in 2011, 2012 and 2013, and now we are doing very well. Other banks didn’t do the same,” says Castagna of BPM.

In this deal, then, Banco’s size was more of a bargaining chip than the relative quality of its loan book.

“It’s a dream deal for Banco, as BPM was the merger partner all the others wanted,” says one analyst.

According to Berenberg, however, BPM would be more valuable on its own because of a stronger balance sheet and lower NPL ratio.

Castagna says the merger will also be an impetus for a more concerted asset-quality push. As the asset quality was part of the negotiations for the ECB’s approval, the bank might now even have more certainty than other Italian banks on its requirements: a target to reduce NPLs by €8 billion by 2019.

That knowledge, indeed, caused brokers at Exane BNP Paribas to reiterate an outperform rating on both banks in June.

But few if any Italian bank mergers have been unmitigated successes. MPS’s merger with Padua popolare bank Antonveneta on the eve of the crisis is a case in point.

The two mutual banks whose capital raisings were rescued this year by the Atlante fund, Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca, also grew through acquisitions, including in southern and central Italy. By contrast, Credito Emiliano, with an NPL ratio of less than half the Italian average, is smaller and focused on organic growth in wealth management.

As those deals show, some of the biggest headaches derive from mergers with popolari banks. This includes, albeit in a less extreme way, Banco’s own mergers in the mid-2000s with popolari in Lodi and Novara. Banco’s original base around Verona is the better-performing part of the group, says Faroni. Its 2009 takeover of troubled affiliate Italease is another reason why it has comparatively high bad-debt levels.

|

Most Italian banks, particularly the popolari, are amalgamations of local mutual banks with peers from smaller cities. Over the past decades, there has been a kind of modern rerun of the late medieval process in which smaller city-states were gradually subsumed into bigger and more powerful ones. But each city’s bank has fought hard to negotiate and maintain the influence of senior staff and as many local employees as possible within the group.

“Cooperative banks are very much linked to the territory, to local constituencies. Not everybody is willing to lose their territorial grip,” says Castagna.

The result is that mergers can add to institutional complexity and perhaps inefficiency in terms of governance and management. They can work, as it is hoped in the current deal, if they are based on sound reasoning and are well-managed, genuinely working towards suitable goals. Yet some in the popolari sector favour mergers, not out of eagerness to improve investor returns (low as they are), rather simply to make it harder for a buyer that might impose even stricter market discipline, once the one-share-one-vote rule ends with the switch to joint stock.

The desire that BPM’s own culture and people were not subsumed was why some at the bank favoured a merger with Banca Carige, and why talks with UBI fell through. Perhaps wisely, it backed out of a deal with Carige, which is not a cooperative, due to the latter’s financial standing. A deal between BPM and UBI or even BPER, however, might have led to a more solid bank, given those banks’ better asset quality compared with Banco’s.

For Banco, the financial strength of its merger partner was as important as geographic fit – in the north of Italy – so it looked at UBI. But for BPER and BPM, smaller banks, it sometimes seemed as if a merger with a weaker but bigger bank would be easier, as it could allow them to maintain their influence.

“It was difficult to find a solution [with UBI] because we wanted a merger of equals. We didn’t want just to have a merger, which in reality was an acquisition,” says Castagna. “Banco was more amenable to this situation.”

Any merger is difficult, he says. “A merger with a cooperative bank is much more difficult, and a merger in this current environment is quite impossible. We are doing impossible things, but which will become possible.”

The market’s fears about Italian banks and the ECB’s demands were therefore just some of the challenges this merger, like others before it, has had to face. The one-shareholder-one-vote rule at BPM and Banco Popolare is still in place until the extraordinary general meetings in October, when the merger and the elimination of those votes must gain mass political approval. Market and regulatory acceptance, and even the acceptance of the top management, is consequently far from sufficient.

“In a cooperative bank, you have to get the approval from everybody,” says Castagna. “There are not 10, 15 shareholders, which represent the majority, which come to the EGM and vote. There are thousands of people, representing different constituencies – local associations, retired people, non-employee shareholders, unions. In our EGM we have 4,000 or 5,000 people, so you need to get a sort of willingness from all of these people to go ahead. At Banco, there are even more.”

Greater sway

For reasons no one seems to remember, BPM’s governance rules give its unions greater sway at shareholder meetings than is the case at other popolari, though Castagna says union influence on management has since retreated.

Shareholders have resisted the conversion to joint-stock status before the reform, but Castagna is confident that they will approve the deal in September. He says the unions have shown rare unity by publicly supporting the deal in a joint press release.

“The employees, as well as the unions, recognize that this is a very difficult market situation, when other banks need public intervention and rescues,” he says. “They see this transaction is a good one, also for them, done without asking any help from anybody.”

Gaining such acceptance, however, has meant designing the merger in a way that is palatable not just to the senior management of the two banks, the regulators and the stock market, but also the ordinary employees. Much of the savings, then, will come from a migration to a single IT system. Redundancies will be limited to 1,800 voluntary early retirements designed to eliminate duplications at the head office and facilitate branch closures, particularly in Lombardy, out of combined total staff of more than 30,000.

Partly to avoid staff relocations, a further 800 staff will be put in other departments, including NPL management and financial advisory. There will be two headquarters, in Milan and Verona, with Milan probably more focused on corporate banking, markets and product development, while Verona will handle retail banking and control – though Castagna says the headquarters may gradually convene to one city or the other.

Such diffusion of head-office locations is nothing new in Italy. It mirrors existing arrangements at Banco: investment banking, wealth and asset management are largely in Milan. Faroni already lives halfway between Milan and Verona, in Brescia. Castagna says a high-speed rail link between Milan and Verona will mean he can easily spend much of his time in both cities.

We will work for more efficiency, to find solutions in the combination of the two different product factories in order to gain more revenues and more profit - Giuseppe Castagna

From Castagna’s point of view, two headquarters are actually an improvement, given Banco’s former bases not just in Verona, but also in the even sleepier towns of Novara and Lodi.

“Banco already had three headquarters, and they will be reduced to one,” says Castagna. “It’s nothing different from Intesa Sanpaolo, which has two headquarters, in Milan and Turin.”

Castagna further defends the decision to carve off roles – in addition to him as CEO and Faroni as general manager – for two co-general managers, one from each of the merging banks. Banco’s CEO Pier Francesco Saviotti, who is 74, will become chairman of a new executive committee. Castagna says it will be helpful to have more support in the enlarged institution.

“It’s quite a normal situation, with three people responding to the CEO,” he says.

The general manager will have what Castagna calls an enlarged CFO role, managing finance as well as product lines (including investment banking, Faroni being former CEO of Banca Aletti). Co-general managers Domenico De Angelis (formerly CEO of Banca Popolare di Novara) and Salvatore Poloni, BPM’s chief organizational officer, will be akin to a chief marketing or business officer and a COO, respectively.

Castagna and Faroni both insist there is a proper rationale, as well as real benefits and valuable synergies and market power to be gained from the merger, despite these compromises and the patchy record of past popolari mergers.

“Banco was the best, from the beginning, in terms of industrial fit,” says Castagna. “It’s a sort of wider BPM, because they are very much in Lombardy, they have a strong presence in other regions of northern Italy, and few branches are also in the centre or south of Italy.”

There is also a fit, according to Castagna, that will help improve revenues on the product side, including insurance and asset management. The structure is yet to be decided, especially given BPM’s previous sales of majority stakes in its insurance and asset management firms, though the banks plan to fuse their various businesses here too.

“We will work for more efficiency, to find solutions in the combination of the two different product factories in order to gain more revenues and more profit in the future years from these businesses,” says Castagna.

What has been decided is the format of the merger of the investment banking arms, both of which are 100% owned. BPM’s Banca Akros will become the merged entity’s corporate and investment banking arm. Banca Aletti, which previously also served as the investment bank at Banco, will now house the combined group’s private banking activities.