For John Mahon and Harry Harrison, co-heads of Barclays Non-Core, the bells are no mere gimmick. They are a crucial way to maintain the momentum of the mission to restore the group’s returns to where they should be.

Barclays CEO Jes Staley and chairman John McFarlane have staked pretty much everything on this, even asking shareholders to absorb the pain of a halved dividend for the next two years to help finance it.

Barclays’ corporate and investment bank was one of the industry’s better performers in the first quarter of 2016: revenues fell by only 4% year-on-year, while those at many peers fell by 15% to 30%. Nevertheless, the wind-down of non-core operations is firmly at the heart of Barclays’ strategy right now.

If the task can be pulled off, the prize looks like a big one. Barclays’ latest quarterly results showed the core businesses of Barclays Corporate & International and Barclays UK posting a return on tangible equity (ROTE) of 9.9%. The UK business racked up an enviable 20.5% on its own.

However, taken as a whole, including non-core, the Barclays group ROTE was a paltry 3.8%. No wonder Staley wants the core business “unshackled” from the drag of the rest, as he told analysts on April 27. Success or failure in this unshackling is likely to determine the length of his career at the bank.

|

John Mahon, |

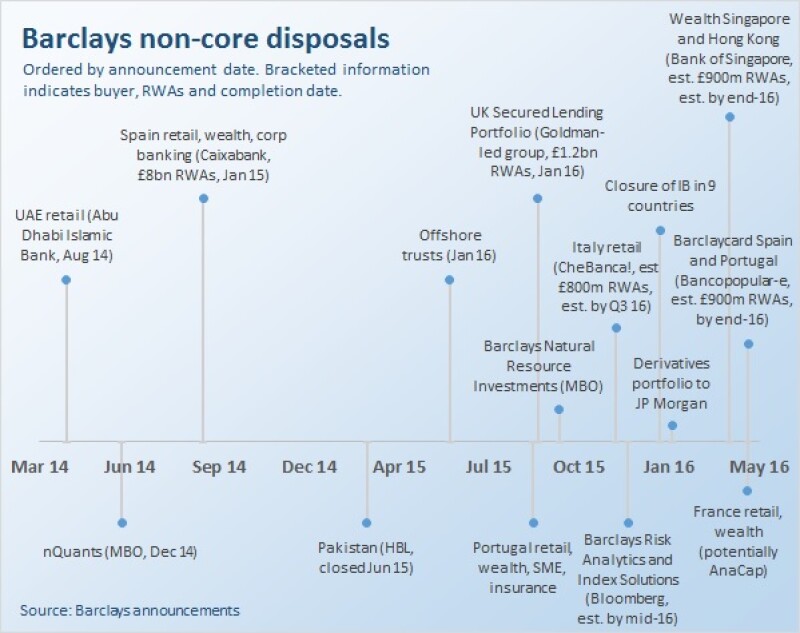

All of which means plenty of pressure on Mahon, Harrison and their team. The non-core division was set up in May 2014 under previous CEO Antony Jenkins, with about £115 billion of risk-weighted assets (RWAs). The bulk were from the investment bank (about £90 billion), and included non-standard FICC derivatives, non-core commodities and some emerging-markets products.

Another £16 billion was accounted for by the European retail banking business, while there were also some £9 billion of corporate, Barclaycard and wealth RWAs. By the end of 2015, outstanding RWAs in the unit had already been cut to £47 billion.

In 2016, new CEO Staley added another £8 billion of RWAs to the scope of non-core, comprising the investment banking operations in nine countries, the bank’s business in Egypt and Zimbabwe (both of which fall outside Barclays Africa), the Southern European credit cards business and the Asian Wealth business – but kept the wind-down target timeframe unchanged.

Since the bank’s announcement this year of its plan to sell down its 62% stake in Barclays Africa, that business has been treated as discontinued, but is not included in non-core.

This year has seen the completion of the sale of a majority of the bank’s Jersey-based offshore trust business as well as its insurance, retail, wealth and SME corporate banking businesses in Portugal.

Agreements have also been announced for the sales of wealth management in Singapore and Hong Kong, retail and wealth in France, and Barclaycard in Spain and Portugal. The sale of the Italian retail business was announced in December 2015 and is slated to complete this year.

Non-core RWAs stood at £51 billion at the end of the first quarter, taking into account the additional £8 billion.

Credibility test

The dividend cut certainly helps in giving Mahon and Harrison the capacity to take some hits along the way if needed. However, with the bank’s equity trading at less than 0.5 times book value, it’s obvious that not all in the market believe Barclays will be able to achieve what it says it will.

That is despite the fact the non-core unit is running well ahead of the targets set in May 2014, when the bank said it would reduce the original £115 billion of RWAs to £50 billion by the end of 2016. The sooner Mahon and Harrison can wrap up the complete wind-down, the sooner Staley will be on the path to proving the strategy right.

Fortunately, the non-core bells – they are in the bank’s London, New York and Singapore offices – have been ringing a lot recently. Whether the disposal is of a tiny loan position or an entire business, the bells ring all the same.

“Throughout our careers, most of us working in this industry have been trying to earn as much revenue as possible for our firms subject to not using too much capital, but here we are focused on reducing the use of capital at speed whilst achieving appropriate value,” says Mahon. “We have to celebrate and keep that momentum each time we do this.”

They are helped by what Mahon describes as a remarkable freedom and sense of purpose. Even non-core has a core, it turns out, and in Barclays’ case this comprises about 200 staff whose goal is purely to effect the wind-down of the unit – there are about 6,000 more in those businesses that sit within non-core.

The 200 are an eclectic mix – many former investment banking staff, but also retail and corporate bankers. Mahon says the differentiator between them and some peers that have also operated bad banks or non-core divisions is that at Barclays they operate independently.

“The purpose of setting up a non-core unit is to show how good the core is,” says Mahon. “But that’s not much good if you don’t actually follow through and exit the non-core.

“Harry and I don’t have another job other than this, and nor does the team. We have a very clear and specific objective – to unwind this division for the best price within the timeframe we have been set – and we know what needs to be done.”

The result is a motivated operation, even though it is by definition one that will have an end. The core non-core staff have defined leaving dates, and with the exception of a few very specialist positions where continuity is deemed critical, there are also no financial handcuffs.

No one has an automatic passport back to the core businesses, but Staley is known to be a strong believer in internal mobility and it would be surprising if there were no openings for some staff back at the core franchise when the non-core job is done.

Execution challenges

Non-core at Barclays is definitely not a ‘bad bank’, says Mahon, noting that the bulk of the businesses and assets it houses are good. Some have even seen new investment ahead of disposal: new branches were opened in Italy, new products were launched in Portugal.

Neither is the process of offloading the assets a fire sale. The team is busy, but it does have time to sell calmly – the target all along has been for non-core to have been reduced to just £20 billion of RWAs by the end of 2017, at which point the bank might fold it back into the group.

That £20 billion cushion is an important one, since it gives Mahon and Harrison the ability to hold out against anyone who might see an opportunity to suck up assets and operations at rock bottom prices.

“That end-target gives us some capacity,” he says. “Obviously there could have been a worry that our disposals would be seen initially as a fire sale, but in fact the bidding has not been a problem.

“When we first set up non-core we had some fairly hysterical conversations with prospective buyers, but those finished quite quickly when people realized that we were not just selling assets at any cost.”

|

The core non-core team broadly coalesces around four disciplines, reflecting the range of tasks needed within the unit.

There is an M&A-style group that focuses on sales processes, running beauty parades and advising on deals. Next there is a team that has a chief operating officer approach, managing the task of shutting operations or withdrawing from geographies. A trading team is involved with the active management and hedging of legacy positions. Finally, a client focus team busies itself with issues such as novation and the obtaining of consents.

Mahon and Harrison might have certainty over their mission, and plenty of bidder interest in the assets they are disposing of, but that doesn’t mean the execution challenges are not formidable. Regulatory requirements are hefty, as are client consent procedures, and even a relatively small market can throw up complexity.

Portugal, for instance, has a multiplicity of regulatory bodies, and on top of which the bank had to contact every one of its customers in the country to ask for permission to transfer them to new acquirer Bankinter.

Logistics weigh on everything. “You have all sorts of challenges, some of which you can’t predict,” says Mahon. “For instance, we had assumed that we might be able to donate our computers to schools when shutting down our operations but in some countries that’s not possible due to local regulations.”

The regulatory burden is severe, but there is no question that the direction of the strategy chimes with much of the supervisory mantra of recent years. Simplification, a focus on key markets, a smaller footprint – a lot of boxes are being ticked.

Selling off retail branch networks is undoubtedly complex, but other disposals present different challenges. Barclays has big legacy derivative books that it is looking to exit: these still accounted for some £20 billion of non-core RWAs at the end of the first quarter of 2016, down from £33 billion at the end of 2014.

The most realistic option in many cases is novation – transferring the positions to new counterparties – rather than unwinding, since more often than not the reason that the client wanted the position in the first place still exists.

“We were trying to novate on a case-by-case basis for a while, but it was taking a long time,” says Mahon. “So last year we put together a portfolio of Scandinavian swaps, thousands of trades, to see what the interest would be.

“We put it out for tender, saying that we couldn’t disclose the identities of the parties but here are the characteristics of the portfolio. We got a lot of interest.”

|

That encouraging result, and similar efforts with books in Australia and New Zealand, led the team to attempt something bigger, which resulted in the announcement on February 3 that the bank had signed a framework agreement with JPMorgan to transfer a chunk of derivative positions, in a deal known internally as Project Coriander.

The bank has not publicly disclosed the nature of the book or the number of clients affected: Mahon describes it as a substantial sub-portfolio and Staley told shareholders at the bank’s annual general meeting on April 28 it was the biggest novation operation he knew of. Market talk suggests it is mostly interest-rate swaps.

There has been no cherry-picking of the book and a framework for pricing the deal was agreed between the two banks without any disclosure of counterparty names. The process of obtaining client consents will take about two quarters, but the bank was keen to publicly announce the agreement so as not to create nervousness among individual clients.

“This was our way of saying ‘it’s not you, it’s us’,” says Mahon.

The process is a long one, but Mahon is confident it will be successful. The challenge – as always with requests to change counterparties – is that clients perceive it as a hassle.

“On top of that, most of them will be continuing clients of the firm in other areas, so the client experience has to be good,” he adds.

Learning lessons

Mahon chuckles when Euromoney asks him what could scupper his broader mission.

“The board asked us that too,” he says. “You want to have a good answer, but the reality is that there is a not a lot, short of another financial catastrophe. Even volatility like we saw early this year doesn’t really impact the process that much – if we had assets that needed a liquid and stable market in order to be offloaded then those were the first to go when we first started.

“The businesses we are disposing of now are different and the deals we are closing now were all gestating through that difficult period.”

Aside from the useful freeing up of capital, cutting of costs and boosting of group returns that should come with running down non-core, there are unquestionably lessons the core business can learn from the process.

Mahon says one of those is the attractiveness of simplicity, noting: “Bespoke might have looked like a great idea at the time, but it has been the hardest to unwind.” Specialization comes at a cost.

Equally important is the need for great legal entity awareness within the group and a better appreciation of how interconnected different business lines can be across different geographies.

“You have to snip every link all around a business once the disposal has been agreed, and we are doing this between signing and closing,” says Mahon. “The challenge is that none of these things were built with the idea of selling them in the future.”

That’s why Mahon argues that those staff who do make the transition back into the core bank could prove invaluable.

“Once you’ve dismantled your garden shed, the chances are you’ll build a better one in the future,” he says.