Jes Staley looks tired. Sitting in his office the morning after his bank’s annual general meeting, the chief executive of Barclays is downing Diet Coke and trying to forget the traffic that even a partly locked-down London throws his way between South Kensington and Barclays’ head office in Canary Wharf.

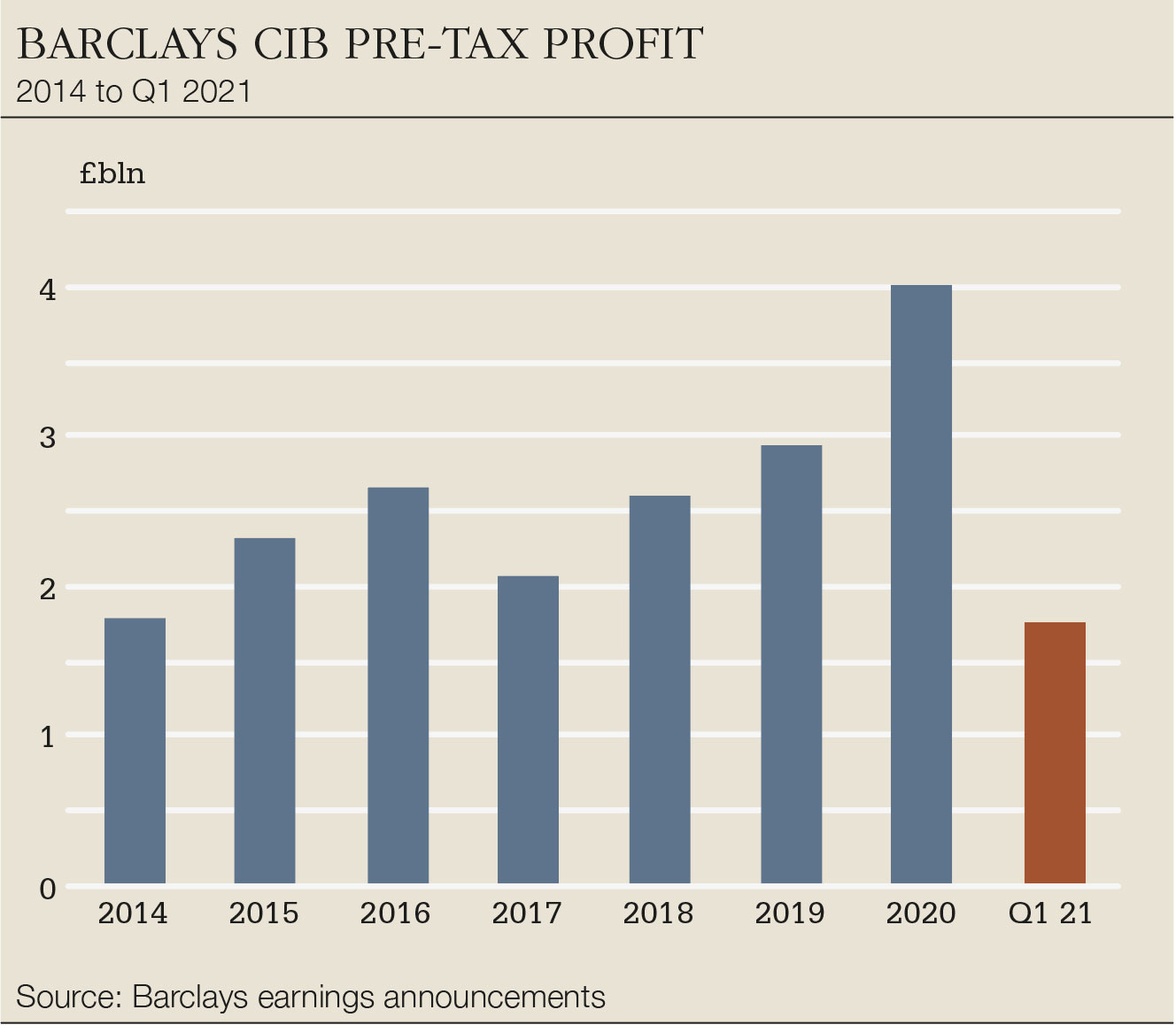

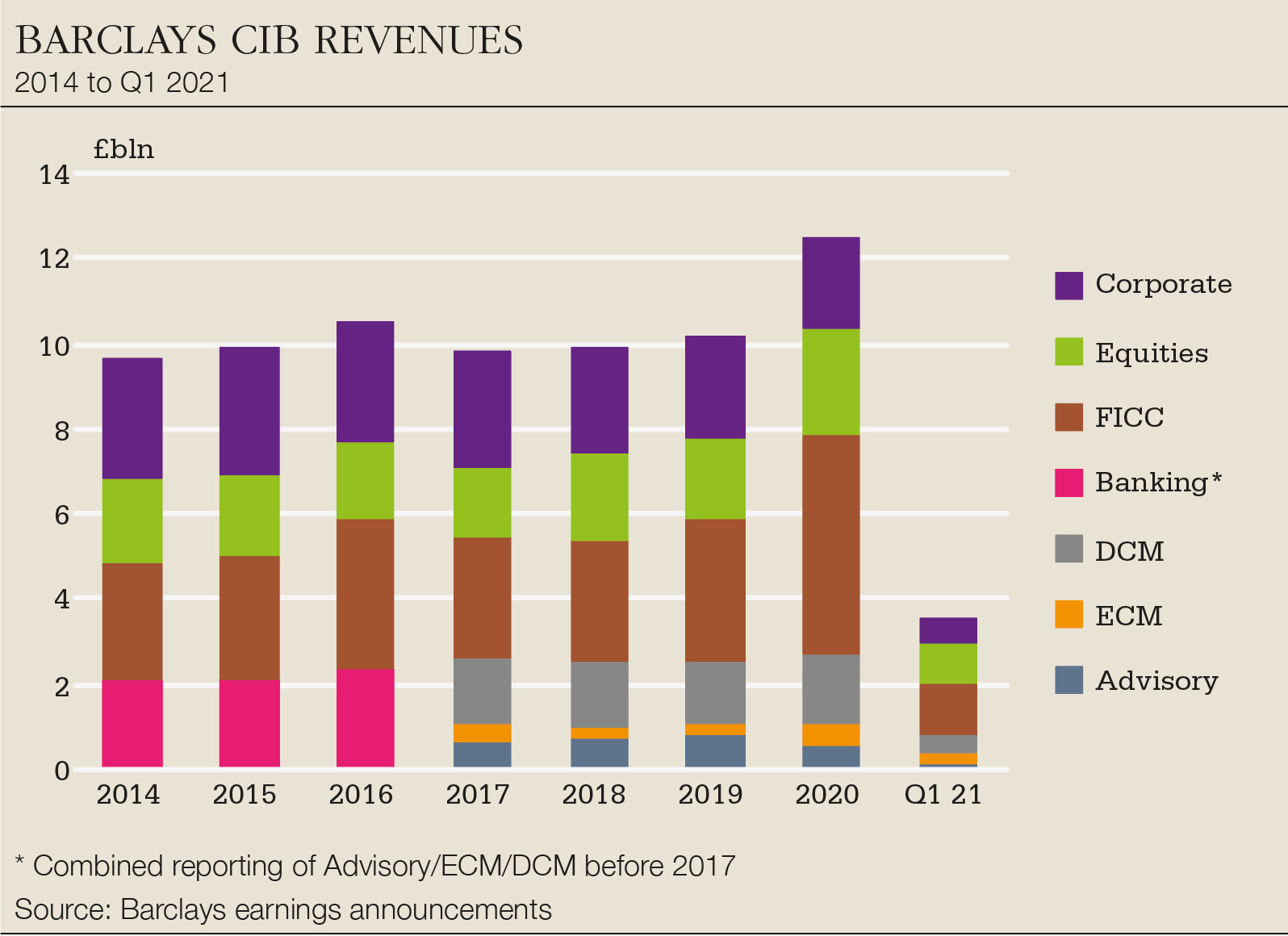

But he sounds upbeat. A few days earlier he was telling analysts about first quarter earnings that saw corporate and investment banking pre-tax profits up by 45% year on year to £1.75 billion. Strip that out and the rest of the bank made £648 million.

with this story

That followed a full-year 2020 result where CIB profits were up 35% to £4 billion. The rest of the group lost nearly £1 billion. The CIB’s return on tangible equity was 9.5% in 2020, compared with 5.4% in 2015. In the first quarter of 2021 it was 18%.

In the year of Covid it was Barclays’ investment bank that bailed it out.

That kind of performance has been a long time coming. The unit seemed to have come through the 2008 financial crisis full of promise after the purchase of Lehman Brothers’ US operations looked set to launch it into the big leagues, only to suffer years of disinvestment and drift after the departure of Barclays chief executive Bob Diamond amid the Libor scandal of 2012. Under his successor Antony Jenkins, investment bankers would quickly learn that the new corporate uniform was the hair shirt.

To judge by the last earnings season and the year before it, the franchise has certainly got back on track during Staley’s five-year watch. Indeed, the day after Euromoney speaks to him, Sherborne Investors Management, the vehicle of veteran activist investor Edward Bramson, announced it had sold its entire 6.1% stake in the bank. In doing so it ended a years-long campaign for Barclays to divest itself of an investment bank that Bramson has argued would stifle returns.

So is the battle over?

Perhaps, but it is more nuanced than that. Looking at recent years solely through an antagonistic lens, as a tussle between Staley and Bramson, Staley looks to have won. But while that matters, he knows there is much more to be done.

While the doubts hanging over the investment bank played out in the market, those inside the bank say they knew the bet was right years ago. For them the unit’s performance through the pandemic is just another data point that confirms it.

And there’s certainly a buzz about Barclays bankers that hasn’t been seen since the Diamond days. “It has been the Bob show, then the Jenkins show and now the Jes show,” says one of the longer serving bankers at the firm. “They are all shows and they all have their own drama.”

Measured take

Sometimes those dramas can define the narrative, even if they are not the whole story. While most investment bankers feel nothing but bitterness for the Jenkins days, it is possible to find some at the firm who offer a more measured take on Staley’s predecessors.

“Antony was good for the time, on the back of Libor,” says one. “A lot of what he did around culture and values is still with us now. And he understood the need for digital investment. Bob didn’t get that bit: he didn’t see the changes that were emanating from retail banking around digital.

“I think what Jes is quite good at is being across all of it.”

That at least is something on which most seem able to agree. In recent weeks Euromoney has interviewed more than 30 senior bankers across Barclays’ corporate and investment bank. When it comes to the core messaging – belief in Staley, belief in the franchise, belief in the ability of Barclays to succeed on the global investment banking stage where other European firms have failed – they practically speak as one. Remote-working Barclays bankers might be missing their water coolers, but they seem to be having no trouble finding the Kool-Aid.

Some bristle at that suggestion. “Well, it is either Kool-Aid or the other option, which is that it might just be true,” says one.

In sticking to his belief in the investment bank, Staley knew he was gambling but was confident he would be proved right. Just why that is goes back – as it does so often – to his days at JPMorgan and analysis he undertook when moving to head that firm’s investment bank in 2009. It is sometimes hard to credit now, but back then JPMorgan was not a top-three firm in the business, despite coming through the financial crisis stronger than its rivals.

Barclays is also still far off being a top-three investment bank. In investment banking pre-tax profits, it sat sixth in 2020. The question occupying Staley at JPMorgan then and at Barclays now is does that matter?

“In many industries there is a common belief that you have to be top three to be successful and a lot of people believe that applies to investment banking,” he says. “So at JPMorgan we looked at every five-year period over 30 years to see who was in the bulge bracket and what was their profitability.

“The first thing you realize is that the bulge bracket changes. The second thing is that the profit number falls off a lot after number six.”

Historically, this bank disappointed with frequency… If you showed faith, you got hit

Jes Staley

That’s a convenient conclusion to draw when you are number six – and the reality is that in the pre-pandemic years BNP Paribas regularly vied with Barclays for that same spot. But Staley’s broad point stands. While he is not going to hold back from trying to usurp at least some of his big US competitors, he is firmly of the mind that being the only relevant non-US investment bank is an objective not to be dismissed. Building in Europe, whether in corporate banking or investment banking, is part of that thinking too.

Not everyone at the firm is at quite the same point in this journey and the Lehman mentality often still lurks just below the surface.

“I hate the rhetoric of us being the best European investment bank,” says one veteran of the firm. “I just don’t consider us to be a European bank, but I come from the Lehman days. What I am focused on is Bank of America and Citi.

“Using our European heritage to our advantage is fine for individual battles. But to win the war, we have to win against the Americans.”

That’s the challenge and means that if Staley’s bet on the investment bank now looks like it paid off, it is not the end of the story. Now he is putting his chips on a second square. It is a less obvious one to the outside world and it won’t garner the headlines of an activist shareholder battle. But it is no less important.

It may, in fact, be much more so. Some areas of the capital markets are growing, but others will not continue to perform as they did in the extraordinary conditions of the coronavirus pandemic, when the scramble to shore up balance sheets lead to a surge in primary financings and volatility drove outsized revenues in secondary.

That means much of the growth that Staley is looking for in the years ahead is predicated on Barclays getting a bigger slice of the business that exists in a normal environment. Part of that is external – some tweaking of geographic footprints here, the odd product added there – but the real job will need to be done internally.

Speak to Staley and his myriad teams about their ambitions and one theme emerges time and time again: collaboration. It underpins everything and is at the heart of what might be the second biggest restructuring he has embarked on – after the restructuring in 2016 that saw the bank exit Africa, cut back to the bone in Asia, close consumer businesses across Europe and slash risk-weighted assets nearly everywhere.

For outsiders the unexpected exit in 2019 of Tim Throsby – brought in by Staley in 2017 to run the investment bank after previous head Tom King had left shortly after Staley arrived – and the placing of the unit under the joint command of Paul Compton, global head of banking, and CS Venkatakrishnan, global head of markets, might have looked like a detail. But it paved the way for Staley’s boldest bet yet.

For any of his plans to come to fruition, he needs this one to work.

Divisions

When Staley came on board at the end of 2015, he found a balkanized bank that did not seem to know where it was going. Just how balkanized quickly became clear.

Staley had only been in the job a few months when he found himself addressing a 200-strong Barclaycard team at an event in Northampton. He duly said all the right things about how great it was to be a part of Barclays with its 100+ years of legacy.

Fixing the plumbing: Staley hunts £900 million opportunity

Barclays chief executive Jes Staley likes to look at Barclays through three lenses: transacting, lending and payments. And the third of these is where particular focus is right now. It might not seem like an obvious place where a collaborative initiative like ‘The Power of One Barclays’ has much to offer, but for Staley it’s a critical part of the picture – as well as a prime example of where he thinks he can find untapped growth.

When he reported the bank’s first quarter earnings, it was his plans for growth in payments that he dangled in front of analysts as they quizzed him on inconvenient matters like higher accruals for investment banking bonuses.

Within the next three years, he told them, the bank can bring in an extra £900 million in annual revenue from payments. Payments accounted for about 8% of group revenues in 2020, or £1.7 billion, so he thinks this qualifies as moving the needle.

If Staley’s priority in recent years has been to stabilize the investment bank and get it into a competitive position where it sits firmly in the sixth spot after his US rivals, where did this new focus on payments come from?

One prompt was a pre-pandemic meeting with Patrick Collison, a 32-year-old entrepreneur who dropped out of MIT in 2009. In 2010 he and his brother founded an e-commerce payments software company, Stripe. It now has a market capitalization of more than $100 billion. Barclays’ is $42 billion.

“I’m flying commercial, but he not only has his own jet, he’s flying his own jet,” says Staley. “And he’s in payments!”

His flippancy belies his seriousness about what he saw was required. He set about studying what Collison did and how the bank could compete. Barclays should have an unassailable advantage in payments, he argues, rattling off the statistics. “We have about 24 million consumer clients in the UK, about 11 million in the US and about 1.5 million in Germany.”

The opportunity comes from the fact that Barclays already has all the different pipes that a UK consumer might use to make a payment – debit cards, credit cards, cash and wire transfers. If it can hook those up properly with all its merchant acquiring pipes – the systems by which businesses receive payments – Staley thinks it would be hard to replicate anywhere else.

It’s odd that it hasn’t been tried before, but it’s back to those silos that Staley hates. The folk that built Barclays’ merchant acquiring systems sat in one place, the people that built the consumer payments systems in another. And business banking was somewhere else again.

“They didn’t talk to each other, they didn’t use the same code or integrate their technologies,” says Staley. “It’s like it was constructed so that you couldn’t connect one to the other. Merchant acquiring is part of Barclays International, small business banking is part of Barclays UK and they didn’t interact.”

To call that a missed opportunity would be an understatement. About 150,000 small businesses open an account with Barclays every year, but until recently those clients were not even asked if they wanted to also open a merchant acquiring account. And doing so later meant starting the process all over again, as it was impossible to transfer the data from one to the other.

Fixing that means rewriting all the code to construct one integrated system. It is, as Staley says soberly, “unbelievably hard.”

Rewiring that tech stack is a job that comes across the desk of Mark Ashton-Rigby, chief operating officer of the bank and its former group chief information officer. Clients now get invited to open merchant acquiring accounts. The data still can’t be transferred automatically, but that might happen by June.

Watch this space.

“When I walked off the stage, I was taken aside by one of our Barclaycard executives, who said: ‘I’m sorry we didn’t tell you before, but we don’t use the name Barclays here, we say Barclaycard,’” Staley says.

That approach extended throughout the firm: it had a divided management team and a divided board.

Nearly six years later, what does he think has changed?

“People are waking up to the fact that we have a vision,” he says. “We have a management team that has been in place for four years and the strategy is cohesive.”

The drive for cohesion is reflected in Staley’s belief that he needs to be plugged into all the facets of the bank. His investment banking colleagues regularly say they can be sure of getting his involvement with big clients when they ask for it. But he also tries to see the manager of his local branch every week to get feedback from the front line of the retail bank.

He talks of branch tellers as “the real heroes” of the firm during the pandemic. Sometimes they take other risks, which he takes equally seriously. One branch was recently held up at gunpoint. “When that happens, you go and see them,” says Staley.

And so to his next big bet: at the core of Staley’s vision of Barclays’ corporate and investment bank now is a simple idea, internally dubbed ‘The Power of One Barclays’. The phrase sounds faintly fatuous; it is hard to find an investment bank that hasn’t toyed with something similar, like ‘One Goldman Sachs’.

But Staley thinks the plan has real meaning at Barclays. It will need to. Whether it is converting financing relationships into strategic equity and M&A or capturing the next big idea in payments or rebuilding in Asia or unlocking the potential of the corporate cards franchise, all roads lead to the same destination: mobilizing the corporate and investment bank’s scattered businesses, many nurtured in their own little worlds, in pursuit of one common goal.

The Power of One Barclays now explicitly covers about 1,000 of the bank’s clients, but its principles underpin how the bank covers every client.

To judge by his teams, who referenced the initiative in every one of Euromoney’s interviews and hail Compton as its chief proponent, Staley’s belief in breaking down silos has percolated through the firm. But there may be more going on than meets the eye. Time and again, the longest-lived and most consistently successful investment banking teams in the firm speak of their tenure and continuity as keys to their success.

Those teams were more often than not formed within Lehman and many still speak with affection for those days at what was the US’s scrappy outsider. And Lehman had its own version of collaboration, with its talk of a ‘one firm’ mentality. It is sometimes tempting to see ‘The Power of One Lehman’ at work rather than anything much to do with Barclays.

That may be a cheap shot, but it is hard not to note that some areas where Barclays has seen the most success – such as in its storied debt capital markets or leveraged finance franchises – are precisely those that have been historically siloed.

During the Jenkins era, for example, it was that mindset that seems to have kept some teams together, doggedly working through trades even while the bank’s management seemed to have very different priorities.

After yet another horror story about how life used to be, Euromoney asks one otherwise polished senior banker the obvious question: if it was that bad, why did you stay?

The mask slips, the frustration still evident. “Because we knew we were good! We wanted to get through the crap. It was a partnership.” Others have a grimmer take. “I guess we had a high pain threshold,” says one.

There is still a lot of low hanging fruit. We can double our ECM and M&A revenues in the next three years. No other bank can do that

JF Astier

That sounds a lot like the kind of backs-against-the-wall environment where silos thrive – and can have good results. After all, Barclays’ debt capital markets business performed well throughout. Wasn’t that because it was operating with that mentality?

Staley doesn’t accept that and appears put out by Euromoney’s mere suggestion of it. “There is no positive at all to building silos,” he says. “Whatever gain you get from that means destroying much more inside the institution.”

A focus on rewarding people for the financial performance of just their division, he argues, hard-wires a mentality of the wrong sort of competition.

“We never have a discussion about who gets the benefit for a piece of work – we just don’t allow it. If someone tries to do that, they’re gone.” No one, however senior they may be, is excused from that, he insists, including those who report to him.

It is fine talk, but most people are hard-wired to judge themselves by their own performance – and to expect others to do the same. Are Barclays folk really so different? After all, many have worked elsewhere (often JPMorgan). What magic dust is sprinkled on them as they walk through Barclays doors on North Colonnade or 7th Avenue?

They say it is different. They say that other firms don’t walk the talk. “It is obvious that this is rarely executed well,” says one senior banker. “Firms talk about partnership, but it doesn’t happen.”

Filling gaps

Everything on the banking side of Barclays’ corporate and investment bank – coverage, capital markets and advisory – now sits under two Lehman Brothers veterans. John Miller runs coverage; JF Astier runs capital markets.

Astier’s background was in leveraged finance and he was running the US franchise through the Jenkins years. That was a frustrating place to be, with the firm showing little appetite to support it, having lost money on the bridge book in the UK.

Astier remembers his first meeting with Staley. “The first question he asked me was: ‘How big is your business?’ I said it is a big business and told him our run-rate.” Staley seemed unimpressed. “Other banks make multiple times that,” he said.

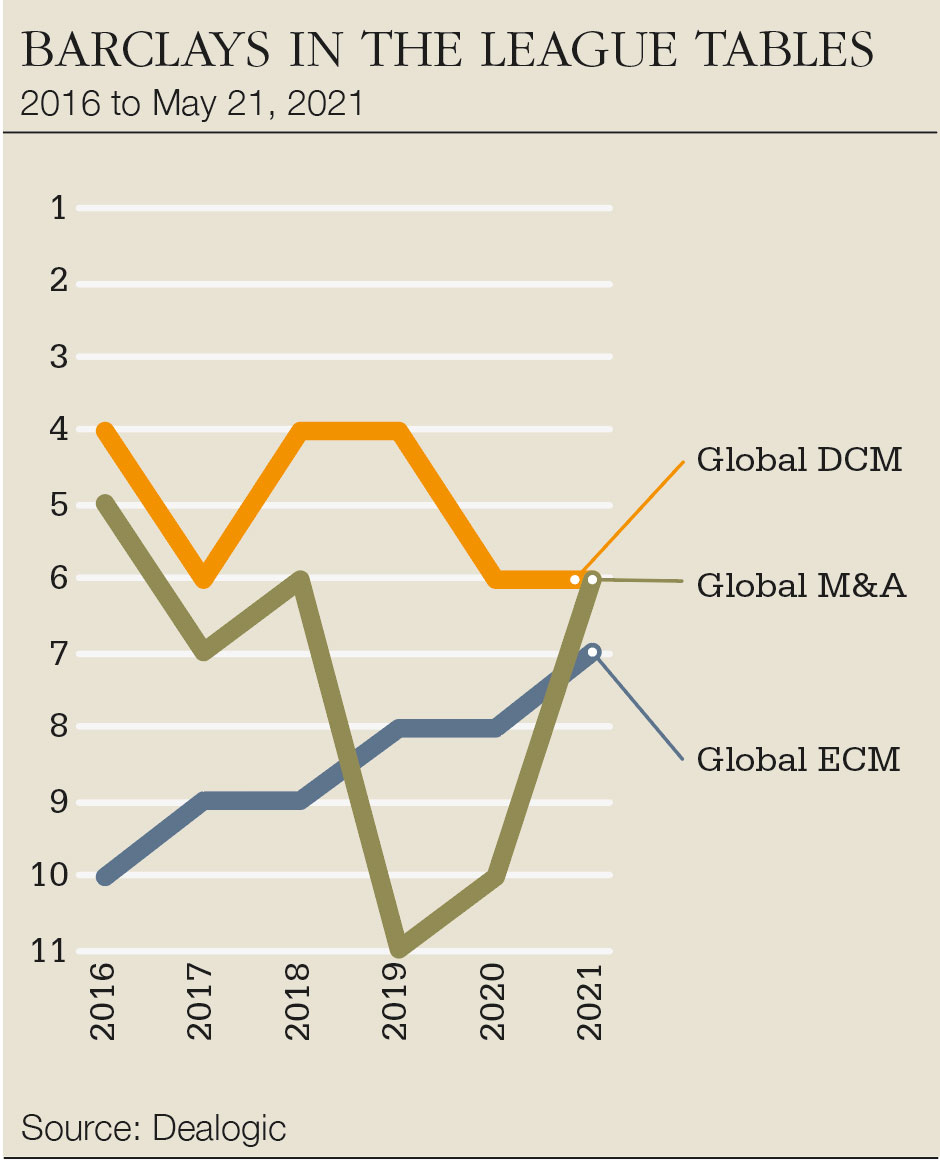

For Astier it was a reinforcement of just how hard it had been to get anything approved. Now that business is consistently top four, DCM is top five and the bank is typically first or second in securitization.

Where the bank lost ground through the Jenkins era and then again as Staley was restructuring the firm, which included a hiring freeze in 2017, was on the coverage side.

“We lost bankers, we couldn’t make the investments we needed in biotech and technology, and now we are on a mission to fill those gaps,” says Astier.

In terms of sectors, Miller identifies the biggest priorities easily enough. “If you look at GDP of the banking opportunity set by sector, there are two over the last decade that have materially outstripped the rest in terms of growth in fees from M&A, leveraged finance, ECM and DCM – tech and healthcare.”

The compound annual growth rate for fees from tech business is 10% over the last 10 years, says Miller. For healthcare it is 12%. Each sector adds up to about 15% of the global investment banking wallet. Within M&A, tech has jumped from about 11% of the wallet in 2010 to 18% now. Healthcare has gone from 9% to 17%.

In equity capital markets it is an even starker picture. Tech has risen from 8% of the wallet in 2010 to 21% now. Healthcare has gone from 4% to 24%.

Both areas are ones where Barclays has arguably been late to the party, more so in tech than healthcare. But Miller says that what the firm has done is to focus on the sub-verticals within those macro groups. In technology that means software, which was about 40% of the tech investment banking wallet in the first quarter of 2021. In healthcare the dominant areas now are life sciences and biotech.

What Miller calls “disproportionate hiring” in sub-verticals looks to be paying off. The bank hired in software coverage and this year ranks fifth in software-related M&A, from a negligible presence just a few years ago. It hired in internet banking – now it ranks sixth. It hired in payments – now it ranks second. About half of the bank’s technology managing directors were hired in the last few years.

In broader tech-related investment banking the bank ranked fifth in the first quarter of this year, gaining 210 basis points of market share, according to Miller. It is certainly progress.

The business is also now benefiting from a fresh approach at the top. Marco Valla, who spent much of his 27 years in banking at Lehman, grew up covering consumer and retail but was asked to take the helm of Barclays’ technology, media and telecom coverage at the start of 2020.

He points to the investment that the bank was already making before he took his new seat. “About 60% of the senior bankers in the tech group today are new to the firm in the last three years,” he says.

When Euromoney speaks to him the bank is about to secure a new senior tech M&A banker and there are approvals for a further half-dozen managing directors in the coming weeks.

Valla says that the bank’s approach to tech as more like a horizontal group than an industry vertical sets it apart from some of the historical market leaders in the sector.

“One of the reasons I have stayed at Barclays is the collaborative nature – my view is that we should use that cultural strength to grow the tech business because today it crosses over every vertical.”

Valla’s consumer background is also serving him well. He is in the throes of several IPO bake-offs right now, with the firm leading with a joint effort between the consumer and tech groups. He has just won a piece of business against a competitor: the client told him that it was entirely down to the way Barclays crossed between the two disciplines.

Valla thinks there is plenty of scope for more tech progress in ECM after the arrival in March 2019 of Kristin DeClark, a tech-focused ECM banker based in California. She co-heads US ECM with Taylor Wright, who joined a couple of months after her.

In 2018, the bank was getting passive mandates in tech IPOs. Now about two thirds of its mandates are as an active bookrunner, which is what DeClark cares about more than just getting on deals. So far in 2021 it ranks sixth for tech ECM; in 2016 it was 10th.

“Barclays has always had a strong syndicate desk and there was an opportunity to capitalize on that and enhance our origination efforts in ECM,” she says.

That sounds like another way of saying that there was more reliance on execution than origination in the past. The need to step up communication with clients is a common refrain.

“You’ve got to dial 9,” says another banker, referring to how Barclays staff get an outside line. It is a mentality that a Lehman veteran like John Lange, who runs industrial and energy coverage, appreciates well. “I used to tell people at Lehman that 31 of the 32 floors were focused on clients – the other one is the cafeteria,” he says.

Missing out on business is a constant in investment banking, but it is why you miss that counts. Another senior banker puts it like this. “There are three types of misses: the ones you were conflicted on, the ones you knew about but couldn’t do anything about and then there are the baseball-bat-around-the-head ones. You are not going to get all the deals, but there should be no surprises.”

Baseball crops up more than once. “You can’t bat 1,000,” says another banker.

We took a huge contrarian position with the investment bank, but I knew that if I got lucky or was right, it would be a good run

Jes Staley

DeClark and Wright are busy catching up in other areas. Special purpose acquisition companies (Spacs), the hot topic of the last 18 months or so in US ECM, were another missed opportunity that they are now fixing.

“Taylor and I have both worked on Spacs at prior firms, but Barclays had something of a legacy view of what the structure used to be like,” says DeClark. “It took a bit of time to change that.” In 2019, Barclays led just two Spac deals, but this year there have been times when it has been ranked top five.

In all US ECM the bank now ranks seventh, below its fifth-place ranking in 2016, indicating how it has failed to capture the shifting importance of sectors during the intervening period. But with two new heads and a more focused approach, DeClark and Wright reckon there is reason for hope.

“Our goal is to be a top-five player in the US,” says Wright. “That will move the needle meaningfully for the business.”

Starting to get traction in ECM has meant overcoming one big hurdle – the incumbency of rivals. Wright hails from Morgan Stanley, but he talks as if he had worked at Lehman. “If we are in that second or third seat, we have to out-hustle,” he says.

He has the support of other businesses in that effort. “We aspire to be top five in every product,” says John Skrobe, co-head of Americas leveraged finance. “We are clearly there in leveraged finance and DCM and we are now making great strides in ECM. We are all pulling together to get that business to number five and the upside that will bring is tremendous.”

Healthcare is a more established franchise than tech at Barclays, but similar themes emerge. Rick Landgarten, who now runs healthcare coverage as well as real estate, arrived at Barclays in 2010 to find a business that had not fared well post-Lehman, with senior bankers leaving.

The exodus continued through the Jenkins years too – there are only two managing directors left from the Lehman days.

But Landgarten has rebuilt a team of 15 MDs and – outside biotech, where the firm still lags – has seen success. The bank ranks top five in healthcare leveraged finance and is typically higher in investment grade debt.

It is a sector that lends itself to a cross-discipline approach. In 2020 the bank advised on the sale of about 10 financial sponsor-owned healthcare companies and financed the buyers of most of them. Landgarten says that the scale of collaboration within the firm is unlike what he has experienced elsewhere.

The bank is advising Thermo Fisher Scientific on its $17 billion acquisition of clinical research services provider PPD, announced in April. But that mandate followed a slew of work related to PPD, including lending, debt issuance and acting as active bookrunner on PPD’s IPO in 2020.

“Culture is what matters,” says Landgarten. “We are not just selling one service but wrapping them all together. Whether it is John Skrobe, who co-heads Americas leveraged finance, or Taylor Wright on ECM, everyone is pulling on the same oar together.”

The power

As befits the man running the part of the bank that provides the industry knowhow that the rest of the bank needs, Miller can’t get enough of the Power of One Barclays.

He is the sponsor of the effort within banking, working with Alistair Currie, the head of the corporate bank, and Richard Cunningham in markets to “socialize the vision”.

Miller tells a similar story to Staley about how things used to be.

“Before Paul [Compton] and Venkat [Venkatakrishnan] were in their seats, the banking business had one executive committee, markets had another.” Now there are no discrete committees, just one for the CIB. “What they did from a leadership perspective was to unite everyone for the common good,” says Miller.

Transatlantic or British?

Back in 2016, Staley was telling Euromoney and the whole world that Barclays was to be a “transatlantic” institution, built around the two hubs of London and New York. But he doesn’t speak like that now. Today the talk is more often of the Britishness of Barclays.

That is no accident, as he himself concedes. “Barclays used to be divided between the most developed financial markets such as London and New York and emerging financial markets such as Brazil, Russia or Africa,” he says. “One of the key decisions we took was to exit emerging markets and focus on the most developed. That was the transatlantic narrative.”

Now, the landscape looks a little different. The bank has long regretted its downsizing in Asia and is beginning to rebuild there. But the reshaping of competitors like Credit Suisse or Deutsche Bank has also fed into the benefits of the Britishness of Barclays.

“Being non-American becomes an advantage for us,” Staley says. “It’s as simple as that.” The reasoning is equally simple. The world’s biggest investors face two critical risks: performance and counterparties. They need diversification in those counterparties – their exposure cannot be all to JPMorgan. But neither can it be all to firms regulated by the Federal Reserve.

This matters for Barclays, where the biggest contributor to revenues today is the buy side. Pitching itself more explicitly as the credible non-US counterparty is more compelling now than it was in 2016.

There is probably a more subliminal reason for the shift in emphasis too. The existential question of whether Barclays ought to be an investment bank at all has occupied the minds of more than just activist Edward Bramson. It has at times been an open question for UK policymakers and regulators alike.

In that context, an emphasis on Barclays as a successful British investment bank is helpful.

But while Staley no longer emphasizes the transatlantic nature of the investment bank in his public pronouncements, his bankers know it still matters more than anything else when it comes to making the numbers add up.

“You have got to have a thumping US presence,” says one veteran of the firm who has served under five different chief executives. “The return on equity of a North America business is very attractive, in the UK it is attractive, in continental Europe it is alright and in Asia it can be challenging.

“Having a US business doesn’t transform your ability to do that business in Europe, but it is difficult to get the P&L to work without it.”

Barclays’ chequered history with its investment bank is testament to that. In the pre-Lehman days, after all, there was a time when the bank had broking, M&A and ECM via its BZW franchise, which it sold in 1997. “We got shot of all of it because we didn’t have the US,” says the banker.

The pandemic might have proved the rationale for retaining the investment bank at Barclays and more specifically its markets businesses, but for those at the firm it has also proved the relevance of the Power of One project.

Sitting in ECM, Wright saw that first hand. “We are really running capital markets with a solutions mentality – and it is not always equity – which is a change in mindset,” he says. “At the outset of the pandemic, JF [Astier] organized daily calls to go through each client’s specific needs, requiring everyone to think holistically, and the legacy of that is a more natural collaboration among ECM, leveraged finance and DCM, which accrues to our clients’ benefit.”

His colleagues in Barclays’ premier franchise of investment grade DCM have long considered themselves fairly self-sufficient. The business is one of the few that consistently stands comparison with any franchise on the Street and is well ahead of most. But even here there are changes.

“In the last couple of years we have been getting calls from our coverage bankers with debt deals where we have not even met the client,” says Pete Mason, the head of DCM in Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA). “It is happening more and more – we get a stream of transactions coming in.” And he says that the culture of collaboration extends to an understanding of when teams turn away business to allow another deal to be done, such as forgoing bond issues in favour of a rights issue.

One new unit where the collaboration focus is explicit is Barclays’ sustainable investment banking team (SIB), run by Brian Reilly, who has been at Lehman and Barclays for 23 years. Much like how Barclays now approaches its tech coverage, SIB differs from traditional industry verticals in that it looks at the bank through a horizontal lens.

SIB is, by definition, regularly partnering with other areas to advise their clients on environmental, social and governance (ESG)-related matters. That might be green financing, but it can also be drafting ESG portions of regulatory filings.

“There are areas that we cover on our own, like agricultural technology, which is a new space for us, but there are others where we have to collaborate,” says Reilly. “The electric vehicles market is so big and has so many adjacencies – batteries, infrastructure, lidar [light detection and radar]. You cannot do this effectively without a spirit of partnership.”

Travis Barnes, global head of DCM and the risk solutions group (RSG), looks at the bank’s securitized products origination business in a similar light.

“At most banks that is probably not as integrated with banking as it is at Barclays,” says Barnes. “Here it is inside banking, but there is no space between us and Scott Eichel [global head of securitized products] in markets at all. It is a fully coordinated partnership.”

He thinks the same about RSG, effectively the banking side of the macro business. “At half the banks on the Street, RSG sits in markets. Here it is in banking and is one business with DCM. And while we have rates sales for flow in markets, the strategic and event-driven piece should sit in banking and we are totally unified with Michael [Lublinsky] who runs macro.

“It is not a case of ‘I want to do the swap’ or ‘I want to do the bond’ – we can do the package. And the client sees DCM and RSG on calls together; we are not suddenly introducing a new person.”

To make all this work clearly takes a certain kind of banker. “Clients have gotten so global that you need bankers who can give them a global lens,” says Barbara Mariniello, Americas head of DCM. “You need to be able to talk about all the different products, all the different parts of the capital structure.”

Mariniello’s colleagues name-check her for her ability to do just that, leading relationships with C-suite executives. “They call her like she’s the coverage banker,” says one.

Barclays has a longstanding financial sponsor prowess in leveraged finance, forged in the Lehman days. Chris Sullivan ran that business at Lehman for 10 years and still does at Barclays.

He notes that the bank’s market share with sponsors still tends to be higher in leveraged finance – where it is regularly at or close to the top of the rankings – than it is in ECM or M&A.

That worked well when leveraged finance was more than half of the sponsor-related fee pool, as it was in the 2015 to 2019 period, but Sullivan knows the bank needs to be nimble as the market shifts. He reckons that sponsor-driven ECM activity is closer to 30% now, compared with about 15% in that previous period.

“When we finance a new buyout, we are using balance sheet on the leveraged finance side, but what we need to do is leverage that incumbency and pull it through to other sponsor activity,” he says. “Once we have financed a buyout, it is incumbent on my team, plus the industry bankers and M&A and ECM, to be on point to pull together.”

Tom Blouin co-heads Americas leveraged finance with John Skrobe and echoes Astier’s view that Staley’s arrival brought a new impetus that the business had not enjoyed under Jenkins.

“Jes had walked a mile in our shoes,” he says. “He understood the value of building relationships with small companies that then turn into platform builders and acquirers.”

Recognition

Many of the examples that bankers cite go to the heart of another driver for the collaboration work, the need to upgrade the bank’s product-specific relationships to something higher – a strategic conversation with clients.

It is the holy grail for any bank but particularly so at one that has historically excelled at financing but not often been able to translate that into a broader franchise.

“I think the biggest change has been the recognition by Jes that a corporate client is a flagship client of the firm,” says one coverage banker. “One of the reasons why JPMorgan is so successful is that every CEO thinks Jamie is their best friend. He makes them feel special. Even under Diamond, Barclays did not do that – he was more of a sales and trading guy.”

In this, Staley is taking his cue from Dimon.

“He spends time with them,” says the banker. “And if you want his office to send a note, he sends a note. With the scale of company that we want to work with, they want to know that the CEO cares.”

I have to be willing to call any CEO at any time of the day and put the bank behind the banker

Jes Staley

Staley says that this strategic upgrading of dialogue is a long journey, but it is one that is close to his heart. He often talks of how he sees M&A as the top of a client relationship pyramid, with everything else flowing from it. Finding the right people is the key.

“What is so difficult about the advisory business is that you need to find a banker who can walk into a boardroom and doesn’t talk about banking but can talk about the company’s business, be it a pharmaceutical or semiconductor company,” he says. “Someone walking in to talk about what Barclays can do as a bank will find they have a very short conversation. So we have to build that, banker by banker.”

Again, Staley brings the focus back to himself.

“I have to be behind that effort – I have to be willing to call any CEO at any time of the day and put the bank behind the banker.”

After a quiet couple of years, Barclays’ M&A franchise is back near the top five, where it has hovered for years. These days M&A falls into Astier’s orbit and he is firmly focused on it.

“We are now putting a premium on the M&A side of the business,” he says. “We know we can win the capital markets work, but we need to show up with strategic content and ideas that will be interesting to a CEO.”

He knows the bank will be missing some opportunities from being selective with its deployment of balance sheet, but he still thinks that the lower market shares the bank has in ECM and M&A compared to DCM and leveraged finance offer a unique prospect.

“There is still a lot of low hanging fruit,” he says. “We can double our ECM and M&A revenues in the next three years. No other bank can do that.”

Heading the M&A team globally is Gary Posternack, who argues that the bank’s market share demonstrates that clients view it as a firm that can join the strategic perspective with its financing capabilities.

“On an individual client basis, there are some where we have lending and financing relationships but are not yet in the inner circles,” he says. “The key to developing those relationships into a more comprehensive strategic connection is through the quality of our ideas.

“There are no shortcuts to building that level of trust.”

Alisdair Gayne, head of UK investment banking, joined Barclays in 2009, when the bank had no M&A or ECM franchise to speak of in Europe, including the UK. Gayne is a veteran corporate broker and it is no surprise that he identifies that business as one of the most important parts of Barclays’ push to become more strategic for its clients.

“The biggest change we could do was enter into corporate broking, because the benefit that gives you is a C-suite relationship focus from day one,” he says. “It meant a different level of engagement from what Barclays had before.”

It has worked out well. As recently as 2012 the bank was 10th in the UK ECM bookrunner rankings. In 2020 it ranked first, the relationships it had built coming good as clients sought to bolster their capital levels during the turmoil of the pandemic.

But UK M&A is the product where the bank has often not been where it wants to be. In 2020 the bank ranked eighth for completed deals that involved a UK buyer or target, according to Dealogic.

But so far in 2021, Barclays ranks second in both completed and announced deals, nipping at the heels of Goldman Sachs, in a market where volumes are already more than half that of the whole of last year.

Gayne maintains that broking is a key route to success. One client situation that he and many of his colleagues reference is Barclays’ work for National Grid. The bank advised the utility in March on its £7.8 billion acquisition of PPL’s UK electricity distribution business and the following month secured the mandate for the pending sale of a stake in its gas grid operation.

In both deals it was alongside Goldman Sachs and Robey Warshaw, the associations speaking volumes for its perception as a meaningful player in strategic work.

National Grid, as Gayne remembers, was Barclays’ first FTSE 100 corporate broking client after he set up the business.

“The product that we get most leverage out of from broking is M&A,” he says. “It gives you the dialogue and the insight into strategy. It allows you to be very thoughtful around what M&A opportunities can exist. You tend not to get that benefit from a debt finance relationship.”

He thinks the National Grid work is the perfect example of the change in how Barclays is now seen by clients. “If you go back five years, I don’t think anyone would have expected to see us there,” he says.

Pier Luigi Colizzi took on his current role of running Europe and Middle East M&A in 2015 – since when he thinks a lot has been achieved.

“If I look at the global banks competing in EMEA M&A, the reality is that in 2015 we were ninth,” he says. “As of the first quarter of 2021, we are now sixth.”

He sees progress all around. Spain, a country where the bank had an obvious gap until recently, last year saw the bank win the mandate to advise a consortium of private equity firms on the €5 billion take-private of telecoms operator MasMovil, the first European public to private deal following the outbreak of the pandemic.

“We stepped into this transaction to provide leading advice and also got comfortable with a sizeable financing at a time when that might not have been an obvious thing to do,” he says. Now it is paying off again, with the bank advising MasMovil on its €2 billion acquisition of rival Euskaltel.

And Colizzi thinks that there is plenty more to come.

“The plan that we have put together for the development of continental Europe is second to none,” he adds. “The focus on growing the quantity and quality of senior resources in the region in the next 18 months is in order to achieve a top-five position in continental Europe alone. Combined with our top position in the UK, it will make us a true leader in EMEA.”

Those hires have already started. Most recently, Anthony Samengo-Turner joined from Greenhill in April as head of M&A for Germany, Austria and Switzerland, following the hiring of Gauthier Le Milon from BNP Paribas as head of France, Belgium and Luxembourg. Philipp Gillmann joined from Rothschild as head of logistics banking for EMEA, while Manuel Esteve joined from JPMorgan as head of continental Europe ECM.

For Francesco Ceccato, at Barclays for the last 11 years and chief executive of Barclays Europe for the last six months, the investment banking opportunity in the region is obvious.

“We have built programmatically in the corporate bank and in markets, but we didn’t really do that in banking,” he says. “Now we are putting everything under the microscope and looking at how we want to structure and develop it.”

Reid Marsh, head of banking for Europe and the Middle East since 2018, having relocated from running the business in Asia, says that there has already been a big shift in the CIB’s business mix in just the last few years.

“A decade ago, the bank was still mainly a DCM machine, but today some 60% of revenues come from M&A, ECM and leveraged finance,” he says.

For Marsh, the emphasis is firmly on building in France and Germany, which account for about 60% of the investment banking wallet in Europe. But in these countries and elsewhere, this is about more than just hiring more bankers. It is also about empowering the country managers to spearhead the Power of One Barclays in their markets.

Part of that is happening through an initiative that is being quietly rolled out whereby country managers are being recast as country chief executives – the change in title intended to reflect their elevated role in the effort.

“The big insight that we had in Europe with respect to the pandemic is that it makes most sense to recognize that clients are headquartered locally, and when lockdowns end they will want to have much more engagement led at the local level,” says Ceccato.

That engagement will include a greater emphasis on the corporate bank too. In 2018, Barclays began rolling out a digital corporate banking platform across Western Europe, partly as a way to streamline its services for clients in the wake of Brexit. It now offers a cash management platform in nine countries that is the same as what clients see in the UK – and the bank has just kicked off a project to take a similar offering to the US.

David Farrow, head of the international corporate bank, says that the elevation of corporate bank head Currie to the group executive committee has been telling for those within the division.

“The partnership with banking is key – Alistair spends a lot of time with Paul [Compton],” he adds.

There are overlaps to be tapped. “Escrow used to move the needle when rates were higher, since you might be taking very large amounts related to an M&A situation,” says Farrow. “That’s obviously lower now, but it links to a more general theme, which is that rather than just doing the M&A, we should looking at bringing the client’s transaction banking to Barclays.”

Validation

In 2016, Euromoney asked: “Can Jes do it?” It looks like he has answered that question, but was it judgement or luck? Staley knows he has needed both.

“The strategy worked,” he says. “For four years we have been fighting the consensus as to what the bank should be doing, and now I think the reasons for that strategy are showing. We took a huge contrarian position with the investment bank, but I knew that if I got lucky or was right, it would be a good run.”

Analysts recognize it, even when they keep bashing the bank on costs. “Things have changed radically because of the last 12 months,” says Jason Napier, head of European banks research at UBS. “I would not have foreseen the CIB producing a double-digit return.”

If it takes a pandemic to validate Staley’s bet, how sustainable is it? Napier says that 2020’s strong performance at Barclays – and at some other investment banks – may be only partly down to the pandemic.

“Elevated volatility has boosted markets businesses and it is in making markets where investment bank trading tends to make the real money, rather than in primary issuance,” he says. “But I think part of this is also probably structural – the substantially larger debt pools now out there are a fact.”

Nonetheless, Barclays still needs to prove consistency and the firm’s bankers argue that comes with diversity.

“A lot of investment banking businesses operate on a sine wave,” says Lange. “You need enough variety to cancel that out and offer investors a decent return on equity, not just having every year be a nail-biter.

“In the old days of investment banking it would be about putting on the big trade and having a blowout quarter. Then everyone would wonder why their businesses traded at a P/E of six.”

Staley’s willingness to gamble has paid off, but it is an instructive glimpse into how he approaches his work. “Jes has always taken a point of view and defended it with high conviction, regardless of which way the trade winds are blowing,” says one banker. “He underwrites his view and runs with it.”

That sounds like something that could be double-edged: it has been for him in the past. ‘Key man risk’ typically describes the damage that could be wrought by a rainmaker leaving. At Barclays there have been times when it seemed like it might better describe the liability of having an impulsive chief at the top.

There have been shaky moments. Staley’s personal involvement in righting a wrong, as he saw it, landed him in hot water when he was censured by the UK financial regulator for meddling in a whistle-blowing complaint. His critics have taken aim at him maintaining his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein when he was at JPMorgan, something he has now said he deeply regrets, and then again in the way in which he might have described that relationship to Barclays.

Such embarrassments have led to questions about Staley’s judgement. But to those in the firm, they are a sideshow – and in any case, with the bank performing well, widespread interest in them seems to be fading, even if the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority is still investigating his disclosures relating to Epstein. When Barclays reported its third quarter earnings in 2020 Staley said he planned to be at the helm for at least another two years. His departure has been foretold many times, but right now he certainly doesn’t have the air of someone about to quit.

It doesn’t always look as though shareholders buy Staley’s confidence in the future. Barclays’ shares fell by 9% in the two days after it announced its first quarter earnings. What is the market missing?

Staley shrugs that off, noting that stocks trade as much on technicals as on fundamentals and that profit-taking after a year in which the stock is up nearly 90% should come as no surprise.

That’s true enough – and at the time of writing, the stock had recovered about half of its fall – but it also adds some context to Bramson’s decision to sell out.

Activists, unlike short-sellers, are not in business to profit from failure but rather to make money from improving the investment thesis. If Bramson thought the upside was limited from here, should others too?

It might also be a question of trust, as Staley is happy to acknowledge.

“Historically, this bank disappointed with frequency,” he says. “We would have a good quarter and then have a one-off charge or the Qatar overhang or we would be restructuring, writing off branches in Europe or exiting Africa. If you showed faith, you got hit.”

But he has seen this movie before, when he was still at the firm that he and his colleagues constantly reference – JPMorgan. He remembers a downbeat operating committee meeting there. “We had just had a good quarter, but the stock was down. And Jamie said: ‘Just turn off the stock screen, because it won’t change until we do this again.’”

Faith in JPMorgan has turned out to be rewarded, but Staley knows that the real battle ahead is to match his great rival’s consistency. He thinks it can be done and echoes Dimon’s words.

“It will take time, but last year was the first clean year for a long time,” he says. “Now we just have to do it again.”