By Tony Shale

|

IN ADDITION |

|

|

|

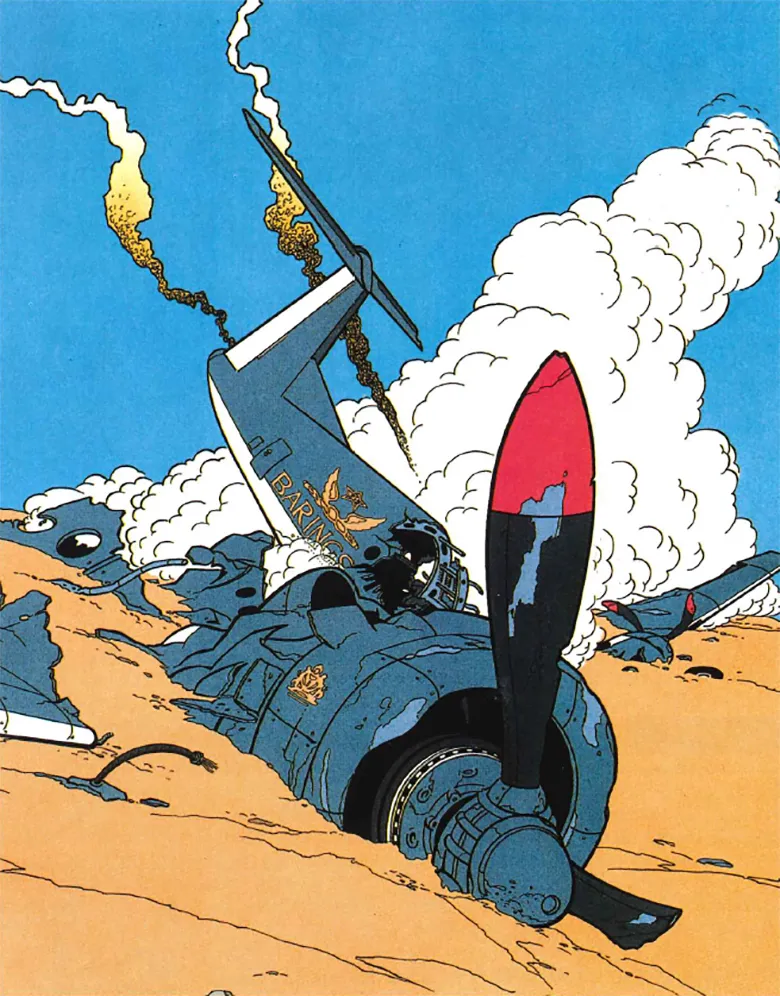

“This is a highly political institution says one of Barings’ senior Asia-based employees. “Departments compete more against each other than against other firms.” It will be months, if not years before the Singapore futures division were able to build up derivatives losses totalling $1.4 billion and bankrupt one of the UK’s oldest banks. But it is already clear that, for several years, Barings has been a bank at odds with itself – particularly in Asia.

Complacency at the top in London, and strife between the merchant bank and the securities operation, allowed not only Leeson’s unit but all the Asian derivatives operations to grow their businesses too fast, without proper supervision.

“Since Baring Securities was established [in 1984], new money has battled old,” says a former employee. “Everything came to a head two years ago.” That was the year the old guard at Barings’ 233-year-old merchant-banking arm, Baring Brothers, slapped down the upstarts at Baring Securities.

In March 1993 Andrew Tuckey, deputy chairman of the Barings group and chairman of Baring Brothers, engineered the departure of Baring Securities’ chairman, Christopher Heath, and directors Andrew Baylis, Vanessa Gibson, Jim Reed and Ian Martin. “It was effectively a takeover of the securities operations by the [merchant] bank,” says a former Baring Securities employee. “You had the unworkable situation of merchant bankers [at Baring Brothers] supposedly overseeing equity traders.”

Barings employees refer to the period that followed the 1993 coup as ‘The Turbulence’. In Asia, it led to a confusing series of personnel moves that eventually left management dangerously weakened. “There has been no continuity of management for the past two years,” is how one former employee sums it up. “It was difficult to say who was in charge of what and where from one month to the next.”

In Tokyo, for example, the long-time branch manager of Baring Securities, Richard Greer, was replaced by Henry Anstey, who shortly afterwards made way for the present head, William Daniel. Daniel had been Baring Securities’ chief representative in Indonesia moving in 1992 to head Seoul. When he left Jakarta, he was replaced by Anthony Davies, previously head of research in Indonesia. Davies then made way for John Marshall, who was formerly in charge of corporate finance in Tokyo.

The upheavals had a direct impact on the Asian derivatives operation. “The team that had built it up from the late 1980s was scattered to the four winds,” says a former member. Among a number of staff losses and transfers, Baring Securities in Hong Kong lost a team of seven from its proprietary trading and derivatives desk to the start-up operation New China Hong Kong Securities.

Baring Securities Hong Kong had once been a reservoir of derivatives expertise. But it lost its pre-eminence in the Asian hierarchy in late 1992 when Willie Phillips, formerly head of all securities business outside Japan, left for Salomon Brothers, and James Bax in Singapore inherited his title and his power.

Phillips’s departure heralded another round of staff changes in Hong Kong. The top job went first to Carl Strutt and then to present incumbent Jeremy Palmer. In the meantime, a number of big names jumped ship. Janice Wallace and Elizabeth Hambrecht, the twin pillars of Baring Securities’ Hong Kong research team, left for Goldman Sachs, and their replacements – Stuart Cook and Adrian Fauré – quickly moved to Morgan Grenfell and Merrill Lynch respectively.

Rise of Singapore

Most significantly, Richard Johnson, who had been Baring Securities’ head of futures and options in Tokyo before moving back to London in the summer of 1992, left the firm in May 1993. “Johnson was the brains of the group,” says a former colleague, “and his departure opened a large hole in the region.” “The pool of derivatives-based knowledge in the region virtually disappeared,” says another former colleague. “And it certainly doesn’t look as though it has been replaced since.” Leeson’s direct bosses in the region could claim little expertise in derivatives. Bax in Singapore enjoys an excellent reputation as an analyst but is thought to have little insight into the finer workings of equity index arbitrage.

|

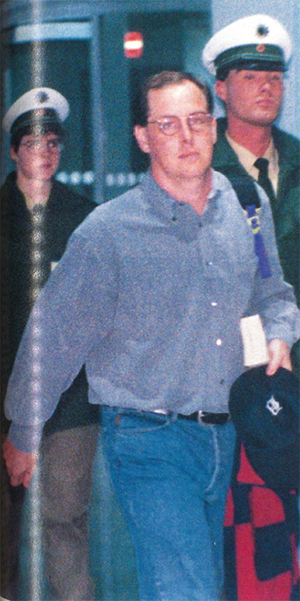

| Nick Leeson, Baring Securities |

“During Willie Phillips’s days in charge, Hong Kong was clearly the stronghold in Asia,” says a former member of the Hong Kong broking team. “After he went, things Became more confused. But Singapore never really took on a leadership role. It was more that operations and management became separated.”

It was against this chaotic background that Nick Leeson rose to become general manager of Barings’ Singapore futures operation. Leeson had joined Barings as a lowly clerk In 1992. Before that he had hardly distinguished himself as a junior clerical assistant at Coutts & Co in London and as a junior operations clerk at Morgan Stanley.

But, by the beginning of 1994, Leeson had parlayed his settlements job at Baring Securities in Singapore into a directorship of Baring Futures there. More importantly – given that he was later to be accused of having manipulated the settlements system – he had developed and installed the back-office system for this division, and had recruited a team of six local floor traders to work at the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (Simex), and a complementary number of settlements staff.

Leeson’s rise came at a time when Barings’ Asian securities operations were again enjoying a period of impressive profitability. Baring Securities had last clashed with Barings’ merchant bankers because of the success (and then failure) of its Japanese equity-warrant business in the late 1980s and early 1990s. And, though it was forced to knuckle under following Christopher Heath’s removal, the bull markets in Asia of 1993 revived its fortunes and its autonomous spirit.

Profits from the securities side soared in 1993 as the region’s bourses rose by an average of just under 100%. Baring Securities was well positioned to benefit. Its policy of building strong research-driven equity-brokerage operations throughout east and south-east Asia (it opened 10 branches in different countries, employing over 700 people between 1986 and 1994) seemed well-justified.

Singapore’s power and autonomy in the region was bolstered by its 1993 profits. Net profits at Baring Futures (Singapore) rose from S$2 million ($1.38 million) in 1992 to S$20 million in 1993, protecting Leeson from outside interference. His profile within the company increased accordingly. “He became the blue-eyed boy who could do no wrong,” says a colleague.

Leeson had built Baring Futures’ reputation in Singapore from nothing into that of a heavy-hitter. Through executing ever-increasing volumes of arbitrage between Simex’s Nikkei 225 futures and those listed in Osaka, he had become known as one of the powerful players in the market.

His apparent ability to keep performing in 1994, while the Asian markets turned sour around him, made him appear all the more valuable. “He was the breadwinner for the entire operation,” says a Baring equity salesman. “They left him alone because he was doubling everyone’s bonuses.”

Bankers versus traders

At the same time, the merchant bankers seemed to be sitting on their hands. Only in February this year did Baring Brothers win its first lead-management mandate for an Asian debt issue (a syndicated loan for Indonesia’s Raja Garuda Mas group).

Executives at Baring Securities in Asia, emboldened by their vastly superior contribution to the group’s bottom line, hardened their resistance to London – which they saw as synonymous with the merchant bank – and exacerbated the long-simmering friction.

A securities trader who was in Tokyo until 1993 recalls: “There was always an uneasy tension between Baring Brothers and Baring Securities. ‘We’re the bankers,’ they seemed to say, ‘heirs to 200 years of tradition, and you’re the jumped-up guys from Liverpool.’ What made it worse was that Baring Securities was phenomenally profitable for a while. But the attitude persisted: ‘OK, you guys did great for five years, but we’ve been here for 200. Don’t tell us how to run the business.”‘ He also remembers an appearance in Tokyo by aloof group chairman Peter Baring – “It was like a visit from the Queen”.

Risk-management and reporting lines, which had been loose before, were totally ineffective. “You had a situation where the securities side was still at loggerheads with the banking side. On top of that, the derivatives side was little understood by either,” says the former Barings man.

“Working in derivatives at Barings was like working in a vacuum,” says a former senior member of Baring Securities’ Asian futures and options team. “To most of the senior guys on both the securities side and in the merchant bank, it was like we were talking a foreign language. They just let us get on with it. We did our own controls and regulated ourselves to all intents and purposes. In hindsight, there wasn’t anyone for us to report to.”

Former employees also claim that senior executives in London frequently betrayed a fundamental ignorance about derivatives. “We used to joke about it,” says one who worked in Asian derivatives. “A colleague once had a good position, for example, where he had bought a very-deep-discount warrant on [Hong Kong-listed] Guangdong Investments and had sold the underlying stock to create what was effectively a fully-hedged long put position. But Peter Norris, chief executive of Baring Securities, called him from London and said that, as he thought Guangdong Investments was heading for a fall, the position should be closed out. My colleague was unable to explain that we would have made money precisely if the stock had fallen.”

Norris, who returned to Barings in 1987 after a three-year stint at Goldman Sachs, is a corporate financier. This year he was destined to head a newly integrated grouping to be called Barings Investment Bank. It would merge corporate finance with the securities and derivatives operations. Like Heath before him, he was not involved in the day-to-day checking of numbers.

Risk management vacuum

But people in London who should have been closer to the numbers, didn’t seem to be. One Hong Kong trader reports that London’s reaction to an estimated $300,000 loss on a proprietary-trading position in Hong Kong was: “Get rid of your positions immediately” – a gift to other firms in the market.

“Barings is not known for being a derivatives house,” says the managing director of structured products at one US investment bank in Hong Kong. “They were playing with fire in Singapore.” A former trader in Tokyo recalls: “No-one in senior management understood derivatives.” That was reflected in the bank’s apparent indifference to updating its systems and reconciling its accounts. “Our back office was hopelessly badly equipped,” says the Tokyo trader. “I recall that between [financial] 1990 and 1991 it took us two weeks to close one year and open the next. It should have been a three-day process. But we couldn’t match the trades.”

There was a dispute between London and Tokyo about the hardware and software for a new operating system. “Our arbitrage department was making money,” says the trader, “and we felt we had the moral high ground on choosing the computers. London thought differently and wanted us to adopt their system. This went on for eight months. I didn’t get involved – it was just too silly.”

Former employees cite a long history of negligence. “It was never clear exactly who we were supposed to report to,” says one who worked at the heart of the Asian operation. “For a long time there was no-one with global risk-management responsibility within Baring Securities. Vanessa Gibson was given the job, though she came from the equity-warrants sales side and was not the ideal choice.

“The gap was not really filled until Ron Baker was hired from Bankers Trust, London [in January 1992], followed by Mary Walz [in June 1992],” continues the former employee. “Baker was supposed to take over the global role on the risk-supervisory committee and, as a director of the board, had a direct line to Andrew Tuckey. But he was also building the fixed-income team [which numbered 180 at the start of February] and was under pressure to get primary-market deals.” Baker and Walz came from the Eurobond and corporate marketing areas of Bankers Trust. “They are bright enough people, but they came from the marketing side,” says a Bankers Trust alumnus. “Baker was a competent deal-maker, even good with using derivatives, but we wouldn’t have given him a risk-management job in our shop.”

Another Barings executive believes Baker and Walz came in “because the [merchant] bank wanted more control over the securities side. They [the merchant bankers] clearly trusted them more than the people at Baring Securities.” But their appointment increased rather than reduced Asia’s appetite for risk: “Baker is head of the entire financial-products group. Walz is head of structured equity derivatives. From London they took the bank in a much more directional, proprietary type of trading.”

A source in Tokyo, formerly at Baring Securities, recalls the meteoric rise of a saleswoman who one day said “Let me have a go”, and did some successful futures trades. “Nobody knew what the hell she was doing,” says the source. “But she made money and head office in London said that, as long as she made money, she could keep going.”

“Nick [Leeson] didn’t like working for them,” recalls the trader. “He’d heard of them joking that a monkey could do his job. They also took most of the credit when things were going well.”

Weak links

Between Leeson in Singapore and Baker in London stood Fernando Gueller. He had been promoted to head of futures and options at Baring Securities in Tokyo (Richard Johnson’s old job) and was, according to colleagues, in daily communication with Leeson on the floor of Simex. “If anyone should have been the first to smell a rat, it was Fernando,” says one. “He had been involved in the futures-and-options division for over four years, after all.”

Gueller is described by a former associate as relatively young – early 30s – and inexperienced. “He was also a difficult guy to talk to, not one of the world’s great communicators, and it is hard to see London getting much out of him.”

The composite picture is of a bank, first-class in merchant banking, stockbroking and research, with a deep-seated mistrust of securities, resisting the securities culture to the extent of sacking the ring-leaders in 1993, only to be beguiled later by the profits made by wily traders. Giving these traders their head, Barings failed to assimilate their culture, and the risk controls that go with it, into the wider bank. And, for their part, the traders resisted assimilation.

One Baring Securities employee, working in warrant trading, remembers the morning meetings after the 1993 coup that deposed Christopher Heath: “There was a member of the bank who would sit in with us. He didn’t say much. I tried to get to know him but my colleagues advised against it. After all, he was from Baring Brothers.”

Additional reporting by Steven Irvine and David Shirreff

Costly sellout to Abbey

In August 1993 Barings moved its 20-strong over-the-counter derivatives team out of the bank and into a joint venture with Abbey National. In doing so, it may have denied itself the important cultural shake-up that active OTC derivatives teams have tended to impose on their host firms.

Almost all banks with derivatives operations have come to accept that swaps and treasury must work hand-in-glove. Swaps for clients are priced off and sometimes driven by the bank’s own balance-sheet bias, its appetite for risk, and its directional view. The cultural benefit for the bank, from top management down, is that it develops a much sharper sense of its overall risk positions and a healthy mistrust of creative traders. There is no doubt that the richest vein of innovation in financial risk management in the last 10 years has come from OTC derivatives operations. After August 1993, Barings didn’t have one.

Its swap team and its swap book were taken over by Abbey National Baring Derivatives (ANBD) and wedded to the balance sheet of Abbey National Treasury Services. (ANBD has no Barings capital and no exposure to Barings or any subsidiary.) ANBD managing director Graham Bird and senior director Oscar Strugstad remain Barings directors, although they work full-time for ANBD. Two other Barings directors, George Maclean and Christopher Steane, sit on ANBD’s management committee.

ANBD executives argue that the move of the swap group out of Barings would have had no impact on the bank’s exchange-traded derivatives activities, since the group did not, as they put it, “interface” with them. But derivatives dealers say that Barings may have missed out on some of the developments at the forefront of derivatives control. It was not a member of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, although ANBD is. Nor did Barings take part in the Group of Thirty’s 1993 survey on derivatives, which was answered by 300 of the world’s leading financial institutions.

David Shirreff

Barings’ near-death experience

February 23 According to the official version of events, top managers at Barings first learn they have a huge open position on the Singapore and Osaka futures exchanges – including a notional $7.7 billion long position in Nikkei 225 futures, and a $20 billion short position in Japan government bonds and Euroyen futures.

February 24 They inform the Bank of England.

February 25 and 26 A frantic weekend is spent by City and central bankers at the Bank of England and Barings’ offices at 8 Bishopsgate. First they try to locate holders of matching short positions to cap off the exposure. But the short positions are too widely distributed. Then, according to Bank of England governor Eddie George, there is a search among big holders of Japanese securities for those who might want to take some of the position, to prevent a fall in the Nikkei index. The Bank of England approaches the Bank of Japan to explore the possibility of taking the position off the market. “That proved impossible,” says George.

A team from J Henry Schroder Wagg attempts to find a buyer for the group. UK financial institutions, and potential buyers worldwide, consider the purchase but find the exposure on the futures too great a risk. The open position (including an unspecified option straddle on the Nikkei index) is valued at minus £625 million ($970 million). That loss could increase by another $70 million for every 1% fall in the Nikkei index. Such a well-publicized open position would be an invitation for every hedge fund on earth to range itself against the seller. The final, and best, hopes are two outright buyers – one of them rumoured to be the Sultan of Brunei. But they too find the downside risk too big.

February 26, 8.35pm A death sentence is passed on a great British merchant bank. “We came closer than I ever thought likely,” says George. “The fact that we failed was not due to lack of support from the City.”

February 27 Monday morning. Barings is put under the administration of accountants Ernst & Young. Buyers will be sought for all or parts of the Baring businesses. Singapore International Monetary Exchange (Simex) takes over Barings’ futures positions, which so far have generated a loss of more than $789 million.

February 28 Simex puts together a $300 million safety net from members to offset potential losses from Barings’ long futures positions. The Osaka Securities Exchange, where Barings also had long positions, asks Daiwa Securities to sell off as agents the 16,000 Nikkei March futures contracts and 1,000 June contracts in an orderly fashion before March 10. Nikko Securities is asked to close the short futures positions in Tokyo.

March 1 Many funds managed by Barings Asset Management, thought to be ring-fenced from Barings’ insolvency, find that their cash deposits with Barings are likely to be caught up in the workout.

March 2 “Rogue trader” Nick Leeson flies to Frankfurt from Bangkok and is detained by German police.

March 5 ING Bank reaches a conditional agreement to buy Barings’ entire business. Purchase price: £1. Barings’ total loss is estimated at $1.4 billion.