In April, China’s State Council issued a set of policy guidelines expressly designed to boost supervision, risk management and transparency across the country’s $9 trillion stock markets, and inject them with the kind of urgency and vibrancy they were clearly lacking.

The circular’s numerous aims were boilerplate-vague – just as China’s cabinet likes them. Promoting the “high-quality” development of its capital markets was one. Another sought to “more effectively” protect investors’ interests within the next five years. By 2035, its authors pledged to have “basically established” a “highly adaptable, competitive and inclusive capital market” system, all underpinned by “high-quality… securities and funding institutions”.

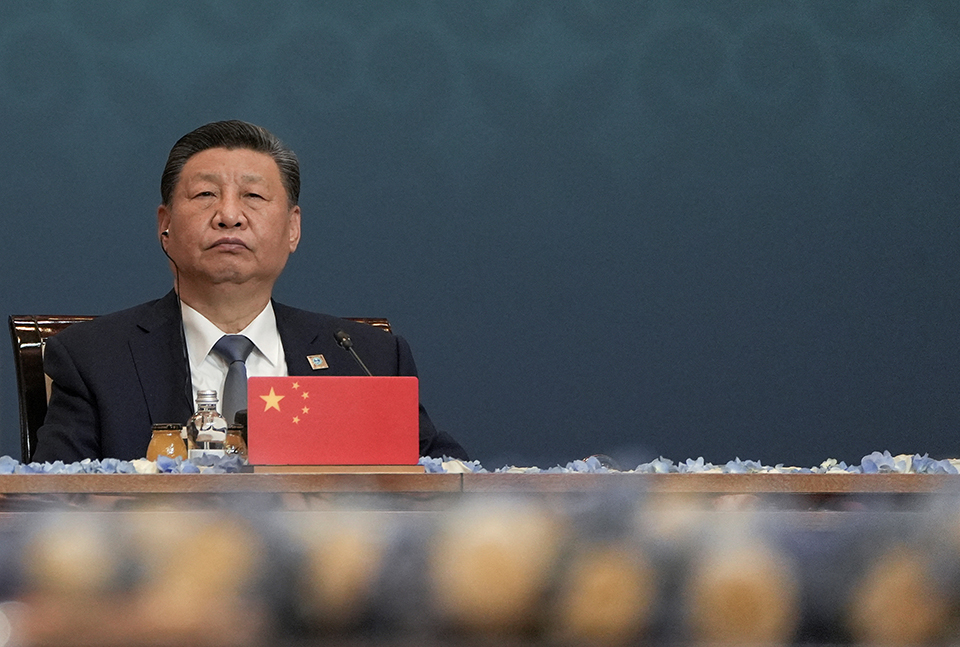

This tells you all you need to know about how the ruling Party, led by president Xi Jinping, views the capital markets in general and, more specifically, the roles played by fund managers and investment bankers.

Xi talks about wanting to promote and protect a system that seems to work so effortlessly elsewhere, most notably in the US. But he can’t bring himself to trust the essential instability of a world where stock prices might soar one day and tumble the next, without necessarily caring about what government thinks. This, in the eyes of China’s cadres, is a world turned upside down.

When China’s leaders promise GDP will grow 5% that year, it magically does. But they cannot issue a diktat that requires healthcare stocks to rise by the same amount

Consider the vagueness of some of its aims. The Party pledges to “basically” create high-quality capital markets by the middle of the next decade, yet in typical fashion, it does not explain how this is to be achieved, either because it does not want to reveal its grand plan or, more likely, because it knows it does not have one.

If Beijing really wanted to build a cohort of well-run investment banks with a growing global presence, it could do so. Once upon a time, it was committed to doing just that. For proof of this, read our 2012 interview with Mary McLeod, then the deputy chief executive of ICBC International, the foreign division of the country’s largest lender.

That was back when Western investment banks, wounded by the global financial crisis, were still in retreat.

McLeod described ICBCI’s aims as “unquestionably to build a global investment bank with Chinese characteristics”, and to instil a “culture… that can sit comfortably in any part of the world”.

Of course, that didn’t happen. After Xi rose to power, he talked up the power of China’s stock markets, only to watch as prices tanked in 2015. He has never quite managed to trust them since, and his wider plans quietly fell into abeyance.

Controlled trial and error

One of the main problems the Party faces is its deeply ingrained fear of the unknown. There is nothing it enjoys more than a sound pilot project. It loves to test-drive ideas in controlled climates: look at how it built a plethora of special economic zones, or consider the Stock Connect system that lets investors in Hong Kong and the mainland trade and settle shares listed on the other market, via their own stock exchanges and clearing houses. These are instances of controllable trial and error.

But stock markets tend to march to their own tune. When China’s leaders promise GDP will grow 5% that year, it magically does. But they cannot issue a diktat that requires healthcare stocks to rise by the same amount in a given year. Not even Nostradamus could micro-manage his way to that kind of success.

Overseas, the problem is magnified. Where Beijing has built a leading position in key sectors (wind turbines, solar panels, possibly electric vehicles), it has been by subsidising them at home, before flooding foreign markets with low-cost goods that often kill foreign rivals.

In the capital markets realm, this is unachievable. How would a Beijing-based investment bank run, say, Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley out of business?

‘Coming soon: world-class M&A advice on the cheap’ is never likely to be a compelling inducement for foreign multinationals or, indeed, Chinese firms with global ambitions.

One word not tacitly included in April’s circular is ‘transparency’, yet it drips from every other sentence.

The State Council variously urges investors and regulators to “strengthen… oversight of information disclosure and corporate governance”, and to “vigorously” introduce new funds into the market to boost long-term investment.

But the glaring problem here is that as Asia’s largest economy continues to slow, the opposite is happening. Since the start of June, international investors have pulled upward of $12 billion out of mainland-listed equities, according to Hong Kong stock exchange data. There is every chance Stock Connect will post the first year of net outflows since its launch in 2014.

Investor wariness is palpable. In the current year to August 21, companies have raised just $5.1 billion from 52 initial public offerings completed across all mainland bourses, according to data from Dealogic. Both are modern records – in that both represent 21-year lows.

Officials have reacted the only way they know how: by restricting access to salient information that would help investors better assess the true value of stocks and sectors. On Monday, daily data that tracks net investment flows from foreign funds into onshore stocks was abruptly made unavailable. Instead, flow numbers will be published on a quarterly basis.

Off script

This is merely the latest in a sequence of such moves. In May, regulators scrapped live trading data that tracked how foreign investors allocate capital across mainland securities. Last year, fund houses were told not to publish the estimated net value of mutual funds. In each case, it was because the data was sending the ‘wrong’ unscripted message to the world.

And herein lies the rub. More than at perhaps any point since the late 1990s, China is in dire need of foreign capital. It is what will power the next generation of would-be, world-class mainland firms, from EV makers to pioneers in everything from healthcare predictive analysis to augmented reality, from space tourism to quantum computing.

As any Shanghai- or Hong Kong-based investment banker well knows, there are hundreds, even thousands, of aspiring Chinese corporates out there, hungry for fresh working capital and desperate to tap new markets and sell shares, ideally overseas.

The problem is that even if global investors believe in them, they may no longer have faith in those who run the country. Restricting the availability of key data and favouring opacity over transparency while claiming to preach the opposite is hardly a case of putting the best foot forward.

Can trust return? Yes, undoubtedly. But will it under the current administration, led by a self-proclaimed president-for-life? That is surely up in the air.

The troubling truth is that Xi Jinping doesn’t like or understand the unpredictability of share markets – and does not trust the non-collective instincts of fund managers and investment bankers.

Worse, this is all happening against the backdrop of a slowing economy undermined by rising costs, deflation and a moribund property sector. Not to mention a growing number of sectors where foreign capital, usually for reasons of national security, is no longer welcome. Little wonder when state officials scour the world for capital, they often encounter suspicion and a general scratching of heads.

If China was once a land of milk and honey for foreign investors, it would be easier to espy a clearer path forward, a way to induce them to return with vigour and belief to a market they once instinctively believed in.

But consider this. Xi Jinping was formally unveiled as president in March 2013. Since then, the Shanghai Composite index, which represents all A and B shares traded on the city’s main bourse, is up 21.44%. Contrast that with the FTSE100 (up 41% over the same period), the S&P500 (up 287%), or India’s BSE Sensex (up 327%).

They say data does not lie. Little wonder Xi Jinping does not believe in it.