There is a longstanding criticism of BBVA among impatient investment bankers. Yes, today BBVA is more profitable, better capitalized and, until now, better valued than its largest Madrid-based rival, Banco Santander. But culturally it is not daring enough, they say. It pays too much attention to price. It misses out on M&A opportunities.

This, according to such critics, is why BBVA’s balance sheet and market cap is still much smaller than Santander, even though Santander was the smaller bank until its 1994 acquisition of Banesto.

Some of this may relate to history and individuals, above all to the many years when Emilio Botín ran Santander while the less deal-hungry Francisco Gonzáles, a former IT programmer, ran BBVA. Similar views are expressed when observers talk about BBVA chair Carlos Torres Vila’s decision to leave late-2020 negotiations for a merger with Banco Sabadell – only to take another look now, four years later, when Sabadell appears much safer but is much more expensive.

Four years ago, BBVA had just sold its US business for almost €10 billion – but not bidding too much for Sabadell was understandable to some.

Today, there are still plenty of sceptics about the merits of revisiting the merger.

BBVA lost €4.2 billion of its market cap on April 30 when news of the deal’s revival emerged. The following day, which was a holiday in Spain, BBVA said the proposed all-share merger would be at a 30% premium to Sabadell’s unaffected share price, valuing the target at €12 billion.

Share prices

Dealing with its UK challenger bank TSB’s subpar returns and unwinding Sabadell’s partnerships in asset management, insurance and payments could prove challenging, according to analysts at Citi. Analysts at Berenberg also say the negative reaction is justified, as the financial benefit of the merger might not outweigh the associated costs and risks.

Besides owning TSB, Sabadell has the fourth-largest share of domestic banking business in Spain, after BBVA, and is particularly rich in Spanish small and medium-sized enterprises, which investors once feared would cause a much larger wave of defaults because of the Covid-19 lockdowns than they did in the end.

But when news broke of BBVA’s return to the negotiating table, Sabadell’s share price was more than five times as large as it was in late 2020.

BBVA’s share price has risen by a lot, too, but not by as much as Sabadell – it is more than three times higher than in 2020. That makes a merger today more expensive for BBVA and its shareholders.

“With the benefit of hindsight, of course BBVA would regret not having bought Sabadell in 2020,” says one senior Sabadell insider shortly before the new talks came to light – suggesting that Sabadell can much more easily go it alone today.

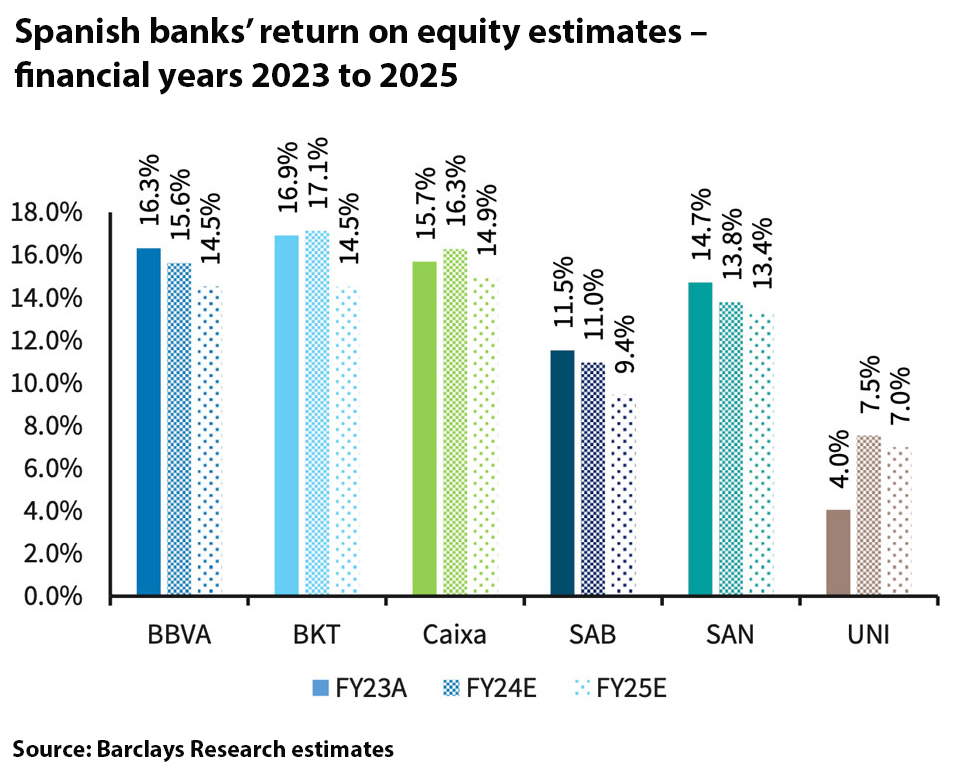

Sabadell’s recovery is largely down to the greater benefit it gains from the much higher Spanish lending margins since 2020, when eurozone rates were negative.

Most of BBVA’s earnings, by contrast, come from owning the biggest bank in Mexico.

But, adds the Sabadell insider, the recovery is also due to actions carried out by Sabadell since it named a new chief executive, César González-Bueno, in the wake of the aborted BBVA talks.

Even now, there could be arguments for why Torres’ previous decision to walk away might be as right today as it was then.

BBVA’s Spanish business is more efficient and profitable than peers, even if it is slightly smaller than that of Santander. Perhaps part of that edge in terms of profitability is to do with a relative lack of recent large and complex M&A in Spain.

Other deals

CaixaBank agreed to buy Bankia, previously Spain’s fourth-biggest bank, four years ago. Santander’s acquisition of Banco Popular happened seven years ago and was harder to digest in some respect.

Most say the Bankia merger – fulfilling what some say was an old dream of CaixaBank powerbroker Isidro Fainé – had much better timing than a new Sabadell deal would have. While negative eurozone rates seemed deeply entrenched in 2020, Bankia was one of Europe’s most troubled banks, heavily weighted to Spanish mortgages, mostly floating-rate deals. Eurozone rates have since rocketed, and with them Spanish interest margins.

The Bankia deal, consequently, was “the deal of the century”, says another investment banker in Madrid a little parochially.

CaixaBank’s dominance of the domestic Spanish banking market now appears unassailable, whatever happens to Sabadell. Bankia, like Sabadell, would have been much more expensive today.

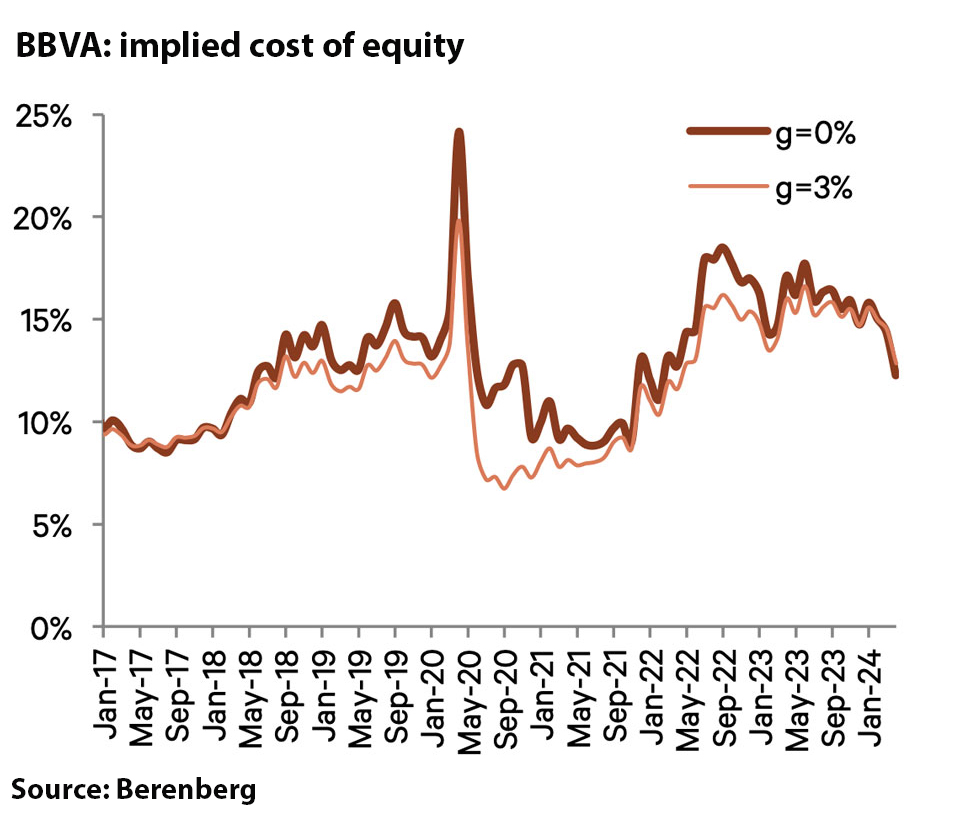

Santander’s 2017 Popular acquisition, by contrast – the first large deal under Emilio’s successor, Ana Botín – appears a bit too generous even to some inside Santander, looking back. The acquisition was perhaps good for the country as Popular was close to collapse, but an associated rights issue had a long-lasting effect on Santander’s cost of equity and brought operational and cultural challenges, too.

Still, Santander gained a much bigger business in its home market, which was its biggest profit contributor in 2023, balancing credit-quality issues in Brazil and the US.

Vote of confidence

Now BBVA’s decision to go back to Sabadell appears, to some, like a potential vindication of the criticism about its lack of daring, and perhaps a vote of confidence in Sabadell’s recent transformation.

Before joining Sabadell as chief executive, González-Bueno was already a well-known and respected figure in Spanish banking. He had built up ING in Spain – arguably the most successful legacy of ING Direct – and later led the restructure of Galicia-based Abanca.

At Sabadell, González-Bueno brought a much needed refocus on risk-adjusted returns, as well as a 30% cut in branches and 20% cut in staff, justified by the legacy of prior mergers and the shift to digital channels.

Senior insiders say this restructuring was done in record time, and the bank was able to grow market share in target areas despite these cuts, thanks to overdue improvements to digital customer onboarding and more modern SME credit approvals. Others in Madrid, outside Sabadell, voice similar respect for its turnaround.

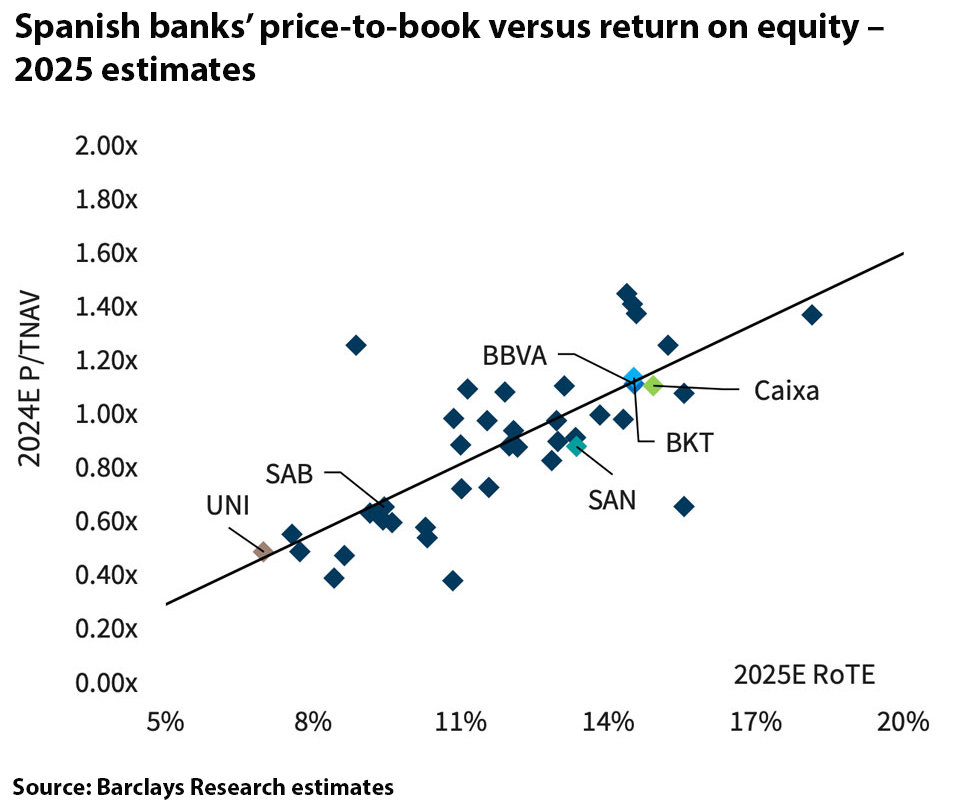

Despite the transformation effort, Sabadell is still by far the smallest and lowest-valued of the top-four Spanish banks, with a discount-to-book value of 30% before news of the BBVA approach, according to Citi.

Much of Sabadell’s balance-sheet clean-up from the eurozone sovereign debt crisis had already happened by late 2020, and it sold its asset management business to Amundi, boosting capital. Yet the recent digital improvements have made Sabadell more appealing to a younger generous of Spaniards, helping to boost its share of consumer finance at a time of sluggish growth in mortgages.

Future growth is worth much more. Those banks that offer growth are worth more

CFO of large European bank

Wider governance and leadership changes have reinforced Sabadell’s rehabilitation among bank investors.

Longstanding chair Josep Olíu Creus has stepped back from executive functions. In 2021, Sabadell also appointed a new chief financial officer, Leopoldo Alvear, who was known in the market as Bankia’s CFO before the CaixaBank merger.

Sabadell, in other words, has carried out the sort of restructuring that an acquiring bank would typically try to do to boost value – leaving less benefit for BBVA to bring.

The wider question, however, is whether this deal or the renewed prospect of it will herald a new and different wave of bank M&A after the incipient upsurge in such deals in 2020, including Bankia’s acquisition by CaixaBank and Intesa Sanpaolo’s acquisition of UBI Banca earlier that year.

Changing thesis

Unlike cases such as Bankia or the old Sabadell, European bank M&A might now be less about survival than growth. That is because European bank shares have recovered dramatically since the lows of 2020, and they have rallied again in recent weeks, especially in southern Europe, thanks to the prevalence of floating-rate loans and better economic resilience compared with northern Europe.

“Investors are becoming more convinced that European banks will meet their cost of equity,” says one bank-focused fund manager, speaking of the recent rally.

Speaking to Euromoney this week, the CFO of one large European bank says there has been a change in “the market thesis” around European banks in recent weeks, as investors finally come to realise that higher rates won’t cause a spike in cost of risk that will more than cancel out the benefit on interest margins.

“The cost of capital of comes down and the risk perception improves in the banks,” says the CFO of the trend related to the macroeconomic picture. “Future growth is worth much more. Those banks that offer growth are worth more.”

BBVA’s share price, too, has traded at a comfortable premium to its book value in recent months, unlike in 2020 when it was trading at a discount of more than 50%. That makes it more convincing to deploy its equity, including the proceeds of its US sale, on M&A, rather than buying back its own shares.

Even UniCredit – always rumoured to be a potential bank acquiror, normally of Commerzbank or Italian lender Banco BPM – is now trading above book value, according to research from Citi.

Four years ago, few believed that was possible. Negative rates and fears of a resurgence in southern European non-performing loans were still front of mind, leading UniCredit to trade at a discount of about 70%.

BBVA, perhaps, is responding to a similar shift – and taking a leaf out of Santander’s old book on M&A.

Torres Villa will be hoping that the new investor confidence will extend as far as supporting M&A, although the slide in its share price on the day Sabadell announced its renewed approach illustrates how questions remain about the merits of such deals.