Every week, Deutsche Bank’s Mark Fedorcik studies what might be one of the most critical metrics for the operating division that he leads, the investment bank. Because if the pandemic has proved anything to people in jobs like his, it is that few things are more important than the one-on-one dialogue between a banker and their client.

“I look at the number of calls our managing directors and directors make to clients each week,” he tells Euromoney. “They log them and we track them, and in the first quarter of 2021 we were up 50% year on year.”

That certainly sounds good, but are those bankers having better conversations? Fedorcik admits that there is no perfect science behind measuring that, although one assumes banks will in time deploy artificial intelligence tools to answer that question too. For the moment, however, Fedorcik says the proof will come out in revenues.

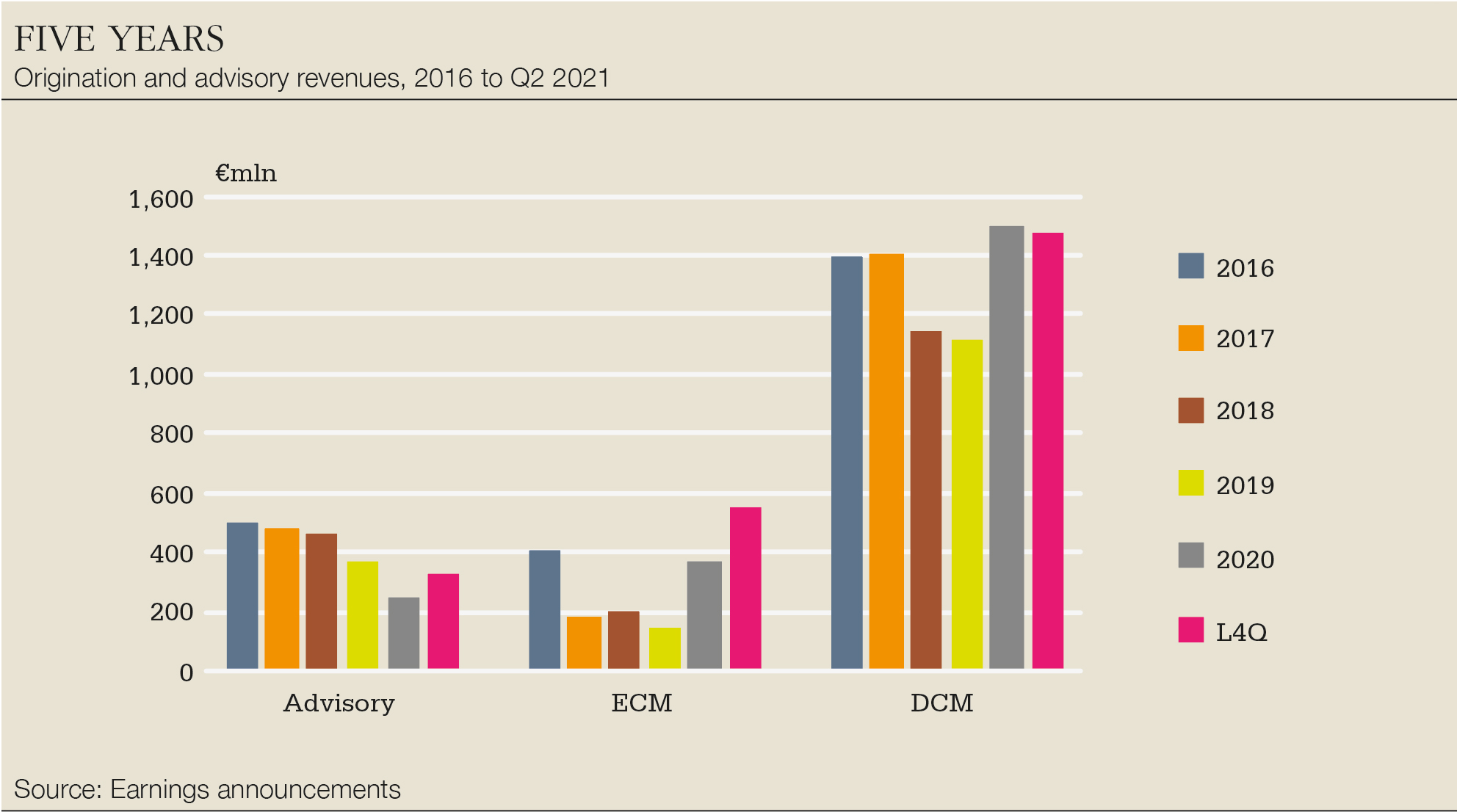

On that score, things are certainly looking bright at the German lender. In the last four quarters the bank’s origination and advisory revenues are up 24% compared with the previous period. Fixed income and currency sales and trading revenues are up 19%.

At €9.8 billion, the investment bank’s overall revenues have been on a tear. In dollar terms, it’s a rise of 27%. It might come as a surprise that this is a bigger jump than at any other global investment banking rival, after stripping out the equities business in which Deutsche Bank no longer participates.

Even in reporting currency terms, Deutsche’s 19% increase is creditable alongside 20% at Goldman Sachs and 22% at Morgan Stanley. It’s from a low base perhaps – Goldman’s business is twice the size, JPMorgan’s nearly three times – but you work with what you have. And Deutsche seems to have been doing that pretty effectively of late.

The performance seems to be a vindication of the Project Cairo transformation of Deutsche Bank announced by chief executive Christian Sewing in July 2019, in which he pledged to reduce or exit areas where the bank could not profitably compete, such as equities trading, and focus on where it could, such as serving its core corporate client base more deeply.

The bank’s rivals sound less sceptical than they did two years ago, even if they maintain that a strategic transformation born of necessity – as Deutsche Bank’s was – is often difficult to make work well.

“It’s hard to shrink to greatness,” says a senior executive at one of the world’s most revered banking franchises. “Deutsche Bank managed to convince itself to get out of equities just as a big equity boom was happening, but they are probably doing what I would have done in their position.

“You have to pick between a bunch of tricky options when you are getting smaller in a consolidating world.”

It’s hard to shrink to greatness. You have to pick between a bunch of tricky options when you are getting smaller in a consolidating world

Senior banking executive

Internally at Deutsche Bank there seems to be no shortage of confidence that the track is the right one. When reporting first half earnings, Sewing said that the previous 2022 target of €8.5 billion of investment bank revenues now looked conservative, given that it would likely surpass €9 billion in 2021. In 2020 it posted €9.3 billion, although the €7 billion seen in the pre-pandemic year of 2019 may be the more meaningful comparison.

European investment bankers say that the pandemic proved that there is a place for big, local investment banking champions like Deutsche Bank and BNP Paribas. Bankers at US firms reluctantly agree that European clients seem to value having that option.

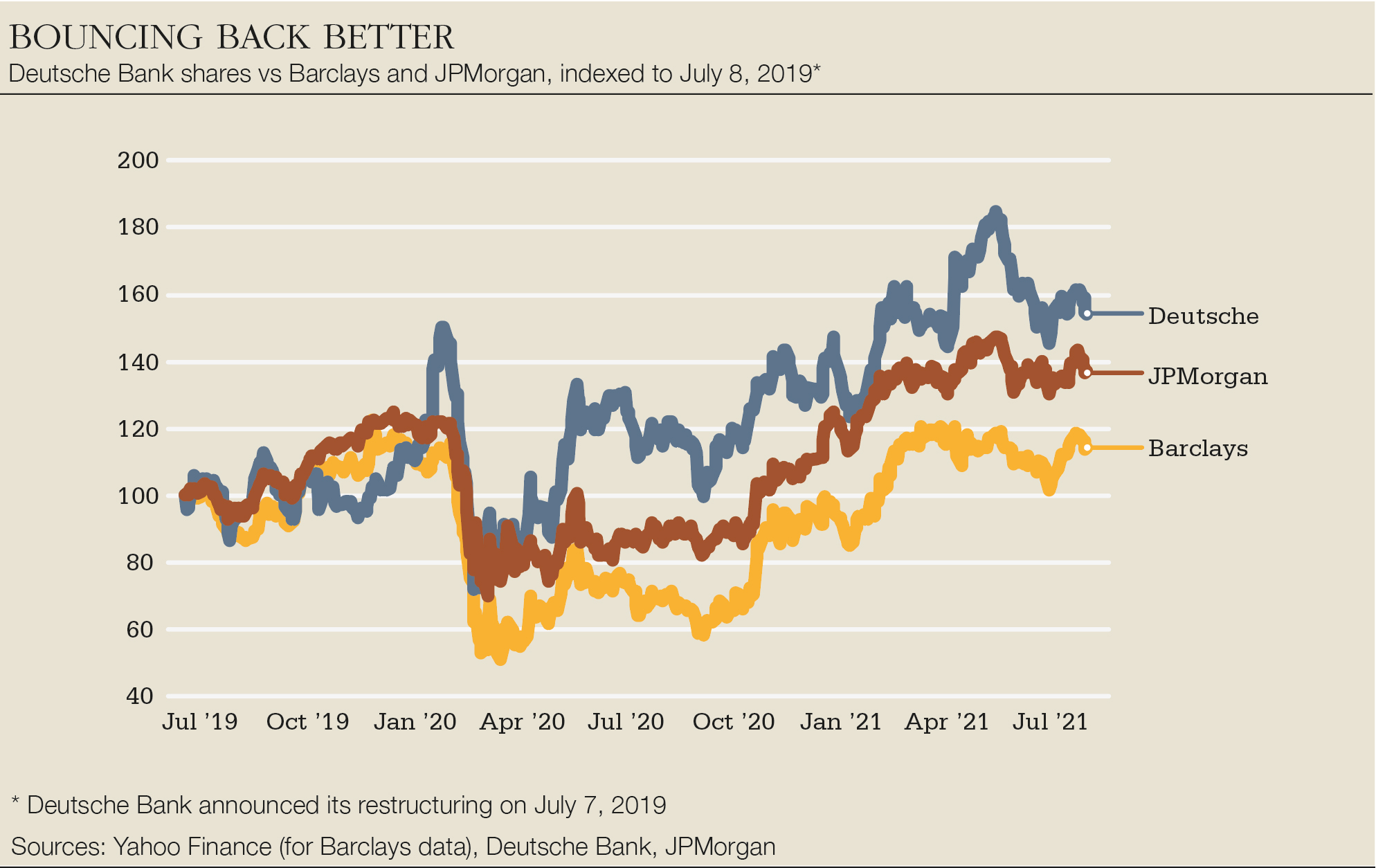

Investors, for the moment, seem to be buying into the story. The bank’s shares are trading more than 50% above where they were when Sewing announced his new strategy on July 7, 2019. Barclays stock is only up 14% over that period; JPMorgan is up 37%.

Much of the bank’s improved return profile is down to the investment bank, where return on tangible equity for the first half of 2021 was 15.5%, up from 10.1% for the same period in 2020 and just 1.1% for the full year 2019. The importance of that is clear from the broader numbers. At 6.5% so far this year, Deutsche’s group return on tangible equity trails the likes of BNP Paribas on 10.6% and Barclays on 16.4%.

The ‘agent’

Maintaining the pace of transformation in the investment bank is now in the hands of Fabrizio Campelli, the enthusiastic 48-year-old Italian who until February was running the bank’s overall transformation.

Deutsche Bank chief executive Christian Sewing has for some time been signalling that he would need to shed day-to-day responsibility for the overall corporate and investment bank, which he has had since announcing the 2019 restructuring, when former CIB head Garth Ritchie left the firm after 23 years. Earlier this year Sewing handed the business over to Campelli.

It was a deliberate decision to pick our spots. Now it is a matter of taking share as our clients get more confidence in the bank

Fabrizio Campelli

The rationale was simple enough. The redefinition of the investment bank was done and had become clear to the outside world. Its financial results were back on track. And Sewing had plenty of other demands on his time. Campelli, meanwhile, had realized that at least some of the work he was doing would now be better executed from inside the operating divisions rather than alongside them.

Although Campelli has passed over his group-wide transformation responsibilities to Rebecca Short, who was head of group planning and performance management, he knows that much of his time will be spent thinking about how to carry his previous focus over into his new role. He describes himself as an “agent” of the support that the corporate bank and the investment bank still need.

He breaks that support down into three areas: the client franchise, which needed rebuilding but now needs careful nurturing; conduct and risk management, ensuring that the bank stays “on the side of what is right,” as he puts it; and technology.

Stretching from back office to front office, this last area is the one where Campelli thinks he will be best placed to help by now being embedded in the business. Deutsche might have made great strides in simplifying its operations – former chief executive John Cryan often used to rattle off to analysts the number of legacy systems the bank had retired in any given earnings period – but there is still much to do.

“It is about how to make the transformation follow through inside the organization, through the middle office and back office,” says Campelli. “That would have been harder for me to do sitting alongside the business rather than leading it.”

That’s partly because it will mean ruffling feathers. Picking one particular system out of several that are doing similar back or middle-office tasks inevitably means some people will be unhappy. But it will be easier now that he is running the show.

That kind of detail is likely to be a factor in Deutsche Bank’s ability to succeed, but for external observers it’s the client franchise – its perimeter and its depth – that looms larger in the mind. And here the bank thinks its client intensity strategy is paying off.

At its investor ‘deep dive’ presentations in December 2020, it said it had cut the number of clients that it designates as ‘platinum’ by 10% from the time of the restructuring but had increased its market share with those clients by 22%, with revenues up 25%. Revenues with the bank’s top 100 institutional clients were up 42%.

Ditching equities

As far as Campelli and his team are concerned the debate about how the bank would fare without equities was put to bed long ago. Deutsche’s equities franchise had over the years become one that was highly dependent on business with hedge funds, with the result that the bank had a lot of exposure to those parts of the business where it is hardest to make money.

Prime brokerage, in particular, takes up balance sheet, is highly competitive and – as illustrated by this year’s meltdown of Archegos Capital Management, which led to more than $10 billion of losses at its banks – fraught with danger. Careful risk management and quick reactions meant that Deutsche Bank avoided an Archegos hit, despite having some exposure, but the episode still proved the point.

Most people’s risk capital went through the roof in the crisis – ours barely moved

Ram Nayak

“For Deutsche Bank, equities trading was no longer a trade-off that made sense – it was consuming too much balance sheet and we were never going to close the gap with the leaders,” says Campelli.

He now argues that not only has ditching most of equities not harmed Deutsche’s reputation in the eyes of clients, it has actually enhanced it.

“It has at times strengthened the relationship, because before they might have felt that they were dealing with a lot of strong businesses and one relatively weaker one,” he says. “Clients want to deal with the best counterparty in each asset class.”

It suits him to say this, of course, but to judge by results in fixed income and in equity capital markets – the latter being the area that rivals often said Deutsche would be unable to sustain – Campelli has numbers on his side.

In ECM revenues more than doubled in the last four quarters, to €548 million. And while its European bookrunner ranking remains low – at 12th so far this year with a market share of about 2.3% – that share is 20 basis points or so higher than it was in 2019. And Fedorcik is confident that it is a platform on which to build.

“To succeed in an IPO, you need an industry banker that covers the client, you need to have balance sheet available, you need research and you need competent product people.” In Josef Ritter and Jeff Bunzl, the bank’s co-heads of ECM, it has two leaders that are well respected in the business.

“We have those four critical ingredients,” adds Fedorcik. “The last piece is trading, where we have execution trading. All of these pieces allow us to compete effectively for IPO and follow-on mandates; and it’s working.”

Dialling back risk

The bank’s fixed income and currency business, the other area where Campelli had feared a negative halo from the decision to pull out of equities, has suffered little disruption, he says. In the last four quarters the bank has gained share in FX, credit and rates, and sits just above Morgan Stanley and just below Bank of America in absolute size, having dropped smaller in the previous period.

At the very start of the pandemic the business consciously dialled back the risk, says Ram Nayak, head of fixed income and currency trading and who has a direct reporting line to Campelli, reflecting the fact that he act as Fedorcik’s partner in leading the investment bank.

“We have gained more market share than any other firm in the industry over the past four quarters,” he says. “Our capital productivity is probably the highest among the big houses.”

The trajectory is very different now. We didn’t have the resources to invest – now we can

Drew Goldman

Nayak also looks at the Sharpe ratio for the business, taking into account its value at risk or stressed value at risk. “Most people’s risk capital went through the roof in the crisis – ours barely moved,” he says. “We didn’t use more capital and we kept risk down.”

That is partly why he thinks the performance even during the pandemic year will be sustainable. The €7.1 billion revenues from fixed income in 2020 compare to just over €5.5 billion in each of 2018 and 2019. The formal expectation at the bank is to make about €6.5 billion in 2021, but it is already on track for closer to €7 billion. If it manages that, it will be an increase of about 25% in dollar terms on 2019 – even the US banks may struggle to match that.

While Campelli might think relationships might have been strengthened by the new focus in the bank’s markets business, Nayak concedes that success in fixed income is more challenging with no equities business alongside it. But he sees that as evidence that Deutsche’s performance has been even more impressive.

“If you are also in equities, you are able to have more conversations and more opportunities come your way, but the fact that we have been able to do what we have done without that is even more striking,” he says.

But for Nayak the key in 2020 was to show stability and discipline, not to reach the €7 billion-plus result that he ended up with. “Everyone wants to write the story that we took on more risk, but we didn’t,” he says. “We had specific instances where we had the chance to quote on dislocated positions and we chose to say no.”

He thinks something similar to Fedorcik when it comes to client intensity. He says the biggest factor in his business has been changing traders’ mindset. Many of the firm’s senior traders and salespeople have an episodic, structured background, where a trade that has taken weeks to construct needs to be profitable.

But Nayak is shifting that mindset more towards flow, where what matters more is an understanding by the client that the bank will be there consistently. Whether that will drift over time to laziness over profitability remains to be seen, but it hasn’t so far.

Unique difficulty

As is the case at its rivals, Deutsche Bank’s investment bank has been flattered by the conditions surrounding the pandemic, with extraordinary levels of stimulus driving asset prices and deal making volumes. That posed a unique difficulty for Deutsche, which had embarked on its pre-pandemic transformation with a specific intention to rebalance its portfolio of businesses away from an outsized reliance on the investment bank.

The new-look Deutsche was supposed to be duller and more stable than before, less subject to the earnings volatility of sales and trading businesses that can outperform in one quarter and crash in another. But in the last four quarters the investment bank supplied 40% of the group’s revenues, compared with 30% in 2019.

Campelli concedes the point but also argues that it’s here that a new, disciplined approach at the bank has also been most evident.

“We said in 2019 that we would strengthen all the engines beyond the investment bank, but of course 2020 played out in ways that benefited investment banking fee pools over others,” he notes. “We did well in that context, but we also stayed true to the strategy because we did not increase the resources committed to the investment bank.”

If you’re not calling a client, one of your competitors is

Mark Fedorcik

Risk-weighted assets in the investment bank are up about 5% from the start of the pandemic, but much of this reflects tweaks in the regulatory treatment of the bank’s internal models rather than any loading up of risk. And costs are down: non-interest expenses in the investment bank for the last four quarters were 13% below what they were in 2019.

Fears that Deutsche might weaken itself perilously as the pandemic hit have not come to pass. Reporting first quarter 2020 earnings last year, Sewing warned that the bank’s common equity tier-1 (CET1) ratio might drop through its internal target of 12.5% as it deployed extra resources to clients.

In the event, however, the 12.8% CET1 and 4% leverage ratio the bank posted in that quarter marked the lows. More than a year on, CET1 stands at 13.2% and the leverage ratio at 4.8%.

Much of the longer-term sustainability that Fedorcik is hunting will be dependent on rebuilding the bank’s standing in advisory. Historically it was one of the strong suits at Deutsche, but its focus began to wane as the bank’s ambitions to be a truly global player were pursued with abandon. Campelli remembers those days, having begun his Deutsche Bank career in 2004 advising financial institutions.

The change in 2019 was to admit that the bank would no longer “cover the waterfront,” as Campelli puts it. Where the bank could not hope to compete, such as with a small natural resources team in Texas, it stopped trying.

“It was a deliberate decision to pick our spots,” he says. “Now it is a matter of taking share as our clients get more confidence in the bank, as they respond to our improved credit default swap spreads, our credit rating and our share price.”

Fedorcik agrees. “If the client is only hiring one or two advisers, you don’t want to be the bank talking about itself,” he says. Deutsche’s bankers are now in the position where they can spend time talking about their clients rather than their own problems, but the reality is that it still takes years to gain the position of trusted adviser.

That makes advisory a long game, but what encourages Fedorcik and his team is that the bank already has strong positions in sectors like industrials, real estate and leisure, and is finding itself able to hire into others, such as technology and healthcare, particularly in Europe.

What Deutsche’s senior management say they will explicitly not do is hire for hiring’s sake. They talk of the supreme importance of culture: the firm has been burned before by getting that wrong.

“We don’t want to work with people who are bad culture carriers – it doesn’t matter how productive they are,” says Drew Goldman, global head of investment banking coverage and advisory. “We don’t want people who are going to be disrespectful to junior staff, it is just not acceptable.

“Equally, we don’t subscribe to the ‘missed deal’ email. If we don’t get a mandate, I don’t immediately think our bankers have been lazy.”

Experience and energy

Practically all the senior leaders in the origination and markets businesses have been at Deutsche Bank – and its predecessor brands in the US – for more than 20 years. They have lived through multiple cycles in the market as well as in Deutsche’s own drama-filled story, but they still manage to sound as if they are excitedly embarking on something new when they talk about the approach under Sewing.

“I have been really impressed with the urgency with which Christian has got us to where we are,” says Goldman. “The trajectory is very different now. We didn’t have the resources to invest – now we can. We can hire selectively and we are on the path to return capital to shareholders from 2022 onwards.”

The combination of experience and energy might be what ends up making the difference this time around. While there have been departures, there is also plenty of institutional memory still stored in those management teams, much of it now recast into cautionary tales about what can happen when a bank’s reach exceeds its grasp.

Those still at the firm generally speak well of Sewing’s predecessor as chief executive, John Cryan, who was the first to tackle the post-2008 crisis reshaping when he replaced Anshu Jain in 2015. But some argue that Cryan also fell foul of the bank’s structure at the very top.

“John was a great transition into let’s take responsibility for our actions, deal with the regulatory issues and the fines, and was always willing to see our clients,” says one banker who spent a lot of time with Cryan in those years. “But I think he was not always willing to make some of the hard decisions, partly because he felt like he was not really in charge.

“Christian acted like a chief executive. He said: ‘The buck stops with me.’ Before, it was more convoluted. People wondered if the buck perhaps stopped with our German supervisory board instead.”

Consistency of management, clarity of strategy and intensity around clients are the three factors that Fedorcik identifies as behind the performance so far. They are three macro themes that many banks take for granted, but it is a long time since Deutsche Bank has had that luxury.

The trick is to keep the bank on the simple, boring and repeatable track that its executives now seem to want more than anything else. But the rival banker was right – shrinking to greatness is hard indeed. The pressure to win only increases as you chase fewer targets.

That’s why Fedorcik is checking that call data every week – after all, banks are only as good as their last mandate and the rivals are formidable. It’s a belief captured in his constant message to his teams: “If you’re not calling a client, one of your competitors is.”

How Deutsche is rebuilding its US reputation

That Deutsche Bank is still playing in the US market seems at times like an oddity. After all, the bank touted its 2019 restructuring as marking a refocus on its corporate clients, particularly in continental Europe, where the origination and advisory business is obviously complementary to a strategy to be the leading investment bank in the region and one of its leading corporate banks.

But the calculation by chief executive Christian Sewing and his team back in July 2019 was that the bank could not afford to cut loose from the US market and still hope to stay credible. It was already shuttering equities by necessity – and was by no means sure how the rest of the business would fare after that. But while the US operations were cut back hard, the thinking was that a business that supported its cross-border clients – both Europeans wanting to be active in the US market and US clients wanting to raise debt in euros, for instance – could be made to work.

“We have a different role in the US and it is also focused on supporting cross-border business,” says Fabrizio Campelli, who now runs the corporate and the investment bank. “We have strong capital markets, financing and advisory capabilities that go back more than 20 years, and those are the core of the franchise.”

Those capabilities go back to its acquisition of Bankers Trust in 1998; a deal that came to epitomize the grand global ambitions that the German bank indulged over the following 15 years, ambitions that would eventually take it from crisis to crisis.

But while Deutsche’s acquisition of Bankers Trust might have marked just another step in the firm’s hubristic journey, it did inject true investment banking pedigree. Bankers Trust had bought investment bank Wolfensohn in 1996 and then 12 months later added Alex Brown, an investment bank that had been founded in 1800.

Much of that pedigree remains and the firm’s bankers say that what matters to clients is that they can bring them good ideas, not where the bank might be headquartered.

“We recently had a sell-side pitch for a fintech company with a venture capital firm that we had not worked with before,” says Drew Goldman, global head of investment banking coverage and advisory. “There was never a discussion about how we were a European bank and this was the sale of a US asset into the US. They told us that we understood the space better than anyone else they had spoken to and were able to bring a unique perspective into the biggest potential buyers.”

Recent history has not been kind to Deutsche’s US franchise. The bank has had regulatory run-ins. It had to cough up $7.2 billion in penalties related to US mortgage securities mis-selling. In 2018, when the bank was buckling under ratings pressure, its US operations failed part of the Federal Reserve’s annual stress test. The Fed said the bank’s controls had “widespread and critical deficiencies.”

Fixing that has taken much longer than executives at the bank would have liked. The Fed was still telling Deutsche that it was sub-standard as the Covid pandemic hit in the spring of 2020. It’s little surprise that Campelli identifies controls as one of his key areas of focus, but it’s also something that has been addressed by a change at the top in the US, with Christiana Riley coming on board as the new regional chief executive in 2019.

Riley’s arrival certainly marked a stabilization. And now the bank looks, if anything, to be doubling down on its US commitment. Fedorcik is based in New York, as is Drew Goldman, global capital markets co-head Sean Murphy and James Davies, head of the institutional client group and head of the investment bank in the Americas.

New offices

When Euromoney speaks to them over the summer, they are about to move offices. Reading symbolism into Deutsche’s abandonment of what its staffers affectionately know as “60 Wall”, sitting in the heart of New York’s traditional wheeling and dealing downtown, might be a step too far. But there’s certainly a message in the bank investing in shiny new offices in mid-town’s Columbus Circle: Deutsche Bank is not planning on leaving any time soon.

And nor should it, while the US accounts for nearly two-thirds of the fee pool, says Fedorcik. “You have to be here,” he says. “And we have our highest market share of fees in the last three years now. We are doing something right.”

Others are more frank. “We are not saying that we are the new Goldman Sachs, but we are also not saying we are just the European tourists in town,” says one senior banker.

But Deutsche is picking its spots, certainly in comparison to the days of the Bankers Trust acquisition and the rampant poaching of teams – many from Credit Suisse – at the start of the millennium. Its approach to the special purpose acquisition company frenzy is a good example, where it has focused on those repeat sponsors that are displaying proven success.

“The intention in the old era was to grow to be a full scale competitor to US banks in this time zone across all products,” says Davies. “Then the big shift in 2019 was to exit equities, at which point it became a different strategy.”

He was one of those tasked with talking clients through that change. He says they understood it, but were equally forthright that they would expect the bank to deliver on its new, leaner model. “Clients were very clear with us: if you are withdrawing from equities because that business didn’t work for Deutsche, we get it, but now we will test you on the depth of your fixed income perimeter.”

That trust was rewarded, Davies argues. “Fast forward to the beginning of 2020 and we saw the ultimate test of liquidity and deployment in the businesses we retained,” he says.

“If you look at our positioning in March and April 2020, for example, our debt capital markets issuance, our US rates business, our commercial real estate franchise, our lending to mid-market platforms – we had depth of liquidity and we stayed the course, and we’ve continued to perform strongly since then.”