In 189 words, Barclays CEO Jes Staley can tell you his strategy. He has done just that in a video for staff. To communicate it, he gives an elevator pitch – and not from just any elevator. This one starts at Barclays’ London headquarters at One Churchill Place. When Staley gets out of it, he is standing at Barclays in New York, 745 7th Avenue.

Across thousands of miles but just seconds of time, he has focused on the bank’s core franchises: retail, credit cards, the corporate and investment bank. He is closing non-core businesses as quickly as he can. He is building a transatlantic, consumer, corporate and investment bank that will deliver double-digit returns. It will be an excellent place to work. It will put customers and clients first.

The result, Staley argues, will be a bank that is trusted and respected by clients in London, New York and anywhere in the world. It will, he optimistically projects, redefine the future of banking.

It is clear that Staley knows what he wants Barclays to be, a question previous senior management appears to have struggled with. But the real question is: can he do it?

Since his appointment was announced by Barclays on October 28 2015, a few things have happened. Not all of them are good.

The good. For a start, a new senior management team is taking shape. The bank has recast itself as one focused on London and New York. It has closed peripheral elements of its investment bank, mostly in emerging markets, and is selling down some well-performing parts of its other operations, including Barclays Africa.

But its core business is returning almost 10%. Group profits on a statutory basis fell 25% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2016, not the best but very far from being the worst among its peers. The businesses the bank intends to focus on as its core saw profits rise 50%.

The bad. Barclays’ share price has fallen by 35% since Staley’s appointment was announced. HSBC’s has dropped 16% and JPMorgan’s by less than 7%. The dividend has been halved for the next two years.

Internally, the bank thinks the right things are happening. Externally, inevitably, the picture is mixed. The banking industry, particularly investment banking, remains under regulatory siege. Many in the business see the outlook for capital-markets fees as poor, even assuming that Europe gradually moves closer to the US in terms of a lower reliance on bank balance sheets.

UK banks have had to grapple with the need to ring-fence their domestic business, to enable the country to cope better with a financial meltdown. To date, Barclays has had a fraught and thwarted history in attempting to agree a ring-fenced structure with the UK regulators, and banking peers say finding a mutually agreeable solution remains one of the biggest challenges Staley faces.

Conduct issues continue to weigh heavily: Barclays’ core businesses had to provision about £1.9 billion ($2.76 billion) in the second half of 2015 alone for current investigations.

That backdrop might be expected to put someone off taking a job at Barclays. There are certainly those in the market that tell Euromoney that they would not have relished it. Others that have left the firm say they are glad to have done so.

It is early days for Staley but something less tangible than numbers is definitely in the air. Staley’s biggest achievement to date is to change the terms of the conversation around Barclays, something his predecessor Antony Jenkins never managed and which helped to cost him his job.

Staley was one of the new generation of bank chiefs that took on some of the biggest jobs in Europe in 2015. Back then, he was bracketed with counterparts John Cryan at Deutsche Bank, Tidjane Thiam at Credit Suisse and Bill Winters at Standard Chartered; each facing a huge challenge to restore the institutions of which they had taken charge. To many other senior bankers, Staley now has an easier task than those three peers. The mission may remain difficult, they say, but it is not impossible.

If Staley ever harbours doubts, he keeps them to himself. Having started in his role on December 1 2015, he is celebrating his six month anniversary as Euromoney goes to press.

He says he likes the fact that Barclays is a large, diversified financial institution – the first of many times that he stresses the importance of diversification. For him this is key to success, as befits a firm that famously sees about one third of UK GDP pass through its payment channels.

“One of the things that I found appealing about Barclays is that it was a very diversified bank and need not rely purely on a recovery in investment banking in order to be successful,” he says. “Being one of the robust retail banks in the fifth largest economy in the world opens up a whole range of positive opportunities. My experience tells me of the benefits of being diversified in terms of consumer and wholesale.”

It is not as if any part of the business is particularly easy, as Staley himself acknowledges. He tells Euromoney that the hardest challenge in his role is dealing with what appears to be real structural impairment in global investment banking. But it is not just there that the challenges lie.

We have enough capital to be a tier-one investment bank

Jes Staley

“The industry is also wrestling with structural changes in the consumer banking space – it’s been so long that people have forgotten what it’s like to run a bank in a positive rate environment,” he adds. “Obviously the equity markets are expressing some doubts about how the industry is going to face those challenges.”

To the sceptics, though, the hiring of Staley represented another strategic lurch by a firm that had seemed for some time uncertain if it really wanted to be in investment banking. Jenkins took the CEO role in 2012 at a time of animosity towards the industry and the bank, in the wake of not only the broad financial crisis but also the Libor-rigging scandal, which had cost the job of the previous CEO Bob Diamond.

Those working under Jenkins were left in no doubt that the firm was to have a very different emphasis with him at the helm; one where the investment bank would play a much smaller part. Between 2007 and 2014, the division moved from accounting for 33% of group pre-tax profits to 25%. More importantly, its risk-weighted assets (RWAs) went from 46% of the group total to 30% over the same period. Jenkins himself presided over the strategy update in May 2014 at which the non-core division was created, a simpler structure was put in place for the group and it was made clear that the importance of the investment bank would be reduced.

Staley has certainly wound back that last point a little. He is not slashing headcount or RWAs in the core investment bank, but nor is he about to let it carry outsized risk. That is why more supportive observers of the firm see his appointment as a logical next step in a regeneration narrative that started with Jenkins.

In this view, Jenkins was the right man to embark upon the cultural change that was needed in the wake of the Libor scandal but was not the right fit at the top when it came to building a transatlantic bank in the face of increasing regulatory complexity and competition for fees.

“Jenkins brought a lot to the bank at a time of crisis,” says one senior banker who served under him and who is still at the firm. “A lot of what he did on culture and values got very embedded very fast. I was one of the doubters about whether this could be done, but I think it has worked and it continues to be embedded.”

A former Barclays banker whose career included the Jenkins and Staley periods goes further, arguing that Jenkins had the better understanding of the firm as a whole.

Jenkins might have made cultural change his priority, but Staley is absolutely on-message when it comes to emphasizing the need to maintain and build on the work done previously. More than once at this year’s annual general meeting, he mounted a firm defence against small shareholders’ scepticism over whether such change was taking place or even possible.

“There will be no let-up in the critically important work to transform Barclays’ culture,” he told the meeting, citing internal initiatives and training that continued to take place to maintain employees’ focus. More than anything, Staley wants banking to be a respected profession in the way that he says it once was.

Preaching cultural change, slashing balance sheet and cutting costs was not enough to convince the board that Jenkins was the one to build the bank for the future, however. John McFarlane, who had joined as chairman only in late 2014, ejected him in the summer of 2015 months later, citing the need for a different set of skills to take the bank to its next level.

To get those skills, he turned to JPMorgan’s Staley, the man widely thought to have been the board’s first choice in 2012, before it changed its mind and opted for Jenkins.

Now that Staley finally is at Barclays, does he really ‘get’ the bank, and more particularly, the investment bank? Some that have left Barclays are doubtful. Those working there think he does. And McFarlane cited Staley’s knowledge of corporate and investment banking in his announcement of his appointment, pointing out that the repositioning of that unit was a priority. Staley’s tenure at the top of JPMorgan’s investment bank, which began in 2009, covered the last few years of a 30-year career at the firm.

The truth is that pretty much anyone was likely to prove motivational to Barclays’ investment bank after Jenkins, but Staley’s understanding of that area is regularly cited and appreciated by those working in the business lines. And not for the first time, his former boss is the yardstick.

“You always hear how Jamie [Dimon] seems to be at every pitch even though he’s also running JPMorgan, but Jes has that energy too,” says a Barclays banker. “He is very busy internally and also very client focused – he spends a lot of time with them.

“Jes seems to be doing so much that you start thinking there must be five or six of him wandering around.”

Hiring pattern

You do not have to be from JPMorgan to work at Barclays, but it clearly helps these days. Group finance director Tushar Morzaria predates Staley, having joined in 2013 from JPMorgan, where he was CFO of the corporate and investment bank. Staley himself has hired CS Venkatakrishnan as chief risk officer and Paul Compton as chief operating officer from JPMorgan, jettisoning former COO Jonathan Moulds in the process after just one year.

That hiring pattern has certainly fuelled the suspicion that Staley is building his own take on JPMorgan, one with a transatlantic flavour. That characterization is probably extreme and Staley would wince at the suggestion that he was mimicking his old shop. But there would also be little to criticize in a plan to emulate one of the leading banking franchises.

Staley has chosen to surround himself with trusted allies from the past, not least because he will need them to help him meet what the Barclays board expects of him. McFarlane is known for being outspoken and for setting tough targets.

It is not surprising, therefore, that some wonder how Staley and McFarlane will work together over time, particularly given the fact that McFarlane was briefly executive chairman, for the period between Jenkins and Staley. He was rumoured to have wanted to hang on to that position for longer, before he was instructed by regulators that good corporate governance demanded he appoint a CEO sooner rather than later.

Internally, though, there appears to be little worry on that score. “McFarlane’s certainly not the shy and retiring type, but he’s fiercely bright and challenging,” says a banker. “He’s obviously a strong chairman, but to his credit he has allowed Jes to get on with stuff, even if it means changing the messaging on things like the dividend. I think the truth is that they are not going to agree on everything but that he will let Jes run the bank while holding him firmly accountable.”

When Euromoney speaks to him, Staley has nothing but praise for the support and experience that McFarlane brings. “John has been terrifically supportive, which has been great,” he says. “He’s been around the block and you have to give him a lot of credit for what he’s accomplished in his career. These are tough times and he’s a staunch defender.”

Staunch defender yes, but some of the chairman’s public comments have not made Staley’s task any easier. For example McFarlane said in July 2015 that he wanted the bank’s share price to double in three years. With the stock down 37% since then, it now has to more than triple in a little over two years to meet that target.

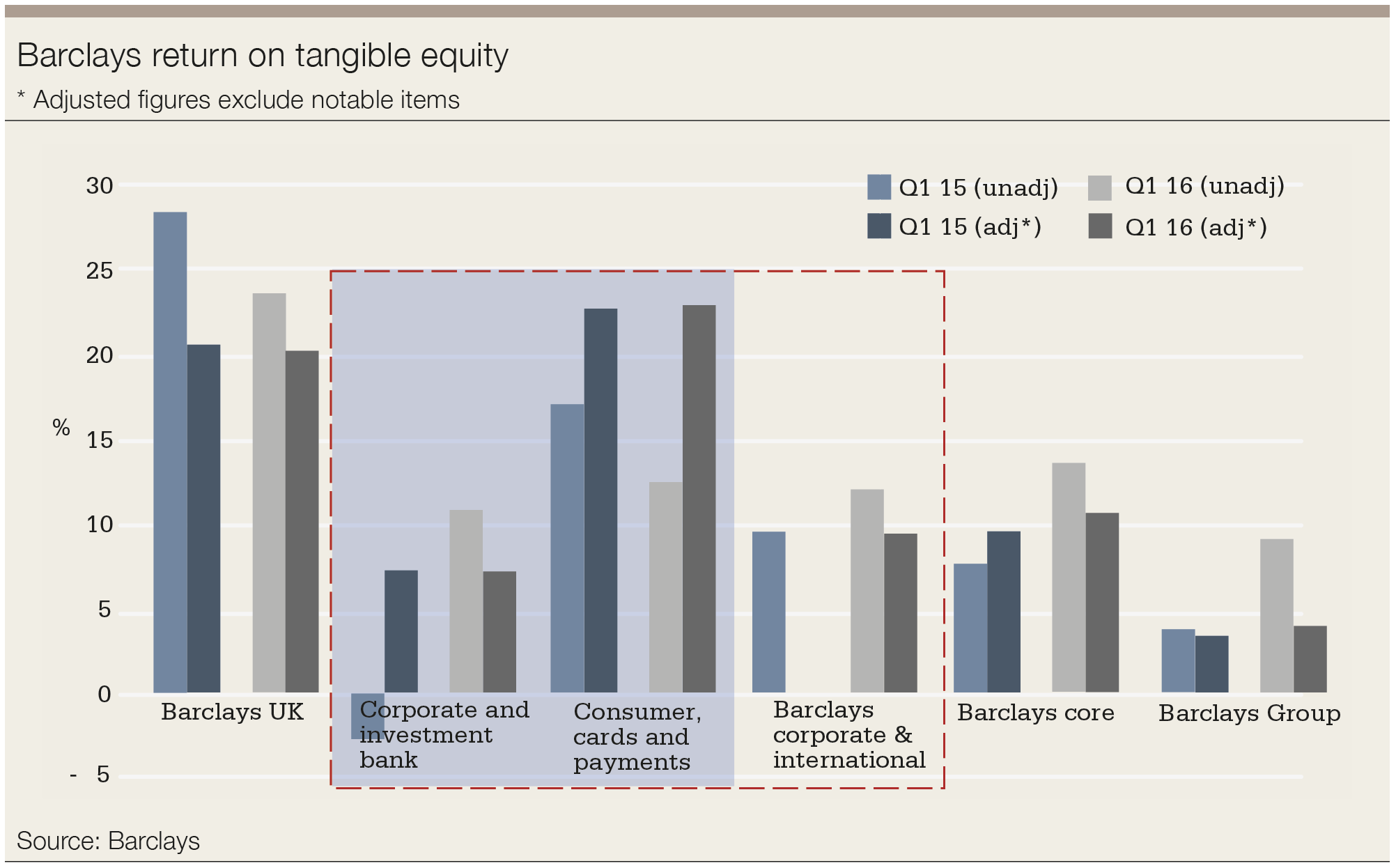

Notching up another objective would be helpful along the way – that of a double digit return on tangible equity (ROTE) at group level. This convergence between group and core returns is at the heart of the bank’s efforts to cut its non-core division’s costs and RWAs. Core return on tangible equity is practically 10% already, but non-core took the group down to just 3.8% in the first quarter of 2016.

Doubts over whether or not Staley can achieve this are certainly reflected in the performance of Barclays shares, sitting well below book value, albeit along with much of the industry. Announcing this year that the dividend would be slashed from 6.5p to 3p for the next two years did not help sentiment about the stock, but the hope is that it will be the key to turning the group around more quickly.

That is because of the headroom that the cut gives management to absorb some hits while they seek to wind down RWAs in the non-core division from an initial £115 billion in May 2014 to just £20 billion by the end of 2017. At the end of the first quarter of 2016, non-core RWAs stood at just £51 billion, after including an extra £8 billion added to the scope of non-core this year.

Those activities deemed non-core stretch from geographic areas of Asian investment banking to Portuguese and Spanish credit cards. In addition, Barclays this year said it would reduce its 62% stake in Barclays Africa so it could deconsolidate it from an accounting perspective, saving it a hefty capital cost (the group must currently hold capital as if it owned 100% of the business). It sold a 12% stake for £600 million through a placing on May 5.

As finance director, Morzaria is closer to the turnaround task than many. But for him the core story is compelling and there is good visibility in the rundown of non-core. “The way I think about it at the moment is that if you take tangible book value of the company, which is about £2.80, give or take, and you look at our 2015 financials, the core business generated about 25p of EPS. So the core businesses are generating a very high return,” he tells Euromoney.

We have two objectives: to preserve and grow our core earnings, and to reduce our non-core losses. I would say we are very confident that they will be dimensionally smaller as time goes by

Tushar Morzaria

“Non-core lost over 9p. So we have two objectives: to preserve and grow our core earnings, and to reduce our non-core losses. I would say we are very confident that they will be dimensionally smaller as time goes by. And it’s easy to project these things, because the disposals are more like M&A activity. When we sell a business like Asia Wealth, the costs and capital fall away, and we know that.”

He cautions on three areas that the bank will have to navigate as it looks to unlock the value of the core business. It must not get caught out by regulatory rule changes, it must cope with legacy conduct litigation and it must maintain cost discipline.

The cost issue is not a simple one, as Morzaria concedes, but he notes that costs have fallen in every year of his tenure. “It’s never easy – it’s not like there are billions of pounds of obvious costs staring us in the eye still,” he says.

“It’s hard work and quite frankly the banking industry was a growth industry for much of the last 20 years. Other industries have got used to operating on thinner margins, but banks will get good at it too. Our core business is already at a 60% cost-income ratio. This will be a way of life for ever and I think about it every morning: how can I be more efficient?”

The internal consensus, for now, seems to be that Staley is making quick progress. His principal strategic initiative came alongside 2015 annual results at the start of March. He announced the reorganization of Barclays’ core activities into two divisions that reflected a new transatlantic focus for the firm: a UK ‘ring-fenced’ bank and Barclays Corporate & International. Of course, Barclays first needs to reach agreement on its ring-fencing proposals with the UK regulators. So far, it has failed to do so.

Last year, Euromoney understands, the bank had been in constructive discussions with the Prudential Regulation Authority about a ‘mother-daughter’ relationship between the two entities, whereby the ring-fenced UK bank would be wholly owned by the rest group.

But those discussions foundered when PRA chief Andrew Bailey insisted such a structure would be against the spirit of the ring fencing rules, and that instead Barclays would need a ‘sibling’ structure with the two entities on either side of the ring fence in a single holding company. Rumours in the UK market suggested that the chairman, McFarlane, had irritated the regulators by leaking details of the discussions to the media.

A sibling relationship could leave the investment bank, struggling to deliver performance, with weak capital levels and a low credit rating at which the bank would struggle to fund itself at competitive levels.

Sources familiar with the situation say that Barclays is still in discussions with the regulators on securing a waiver to allow a mother-daughter relationship at least on a transitional basis. A structure needs to be agreed with the PRA by January 2018 and will come into effect in January 2019.

Combined with the need to separately capitalise its US business according to Intermediate Holding Company rules, Barclays has yet to find a capital structure that works. As the CEO of another major European bank argues: “This is Staley’s biggest problem. He doesn’t want to be raising more capital when the stock trades at 0.7 times book.”

Working structure

Staley clearly believes he does have a structure that works.

“What is particularly compelling about our strategy is the transatlantic approach,” argues Staley. “If you look at the new way in which we are presenting and managing the bank, with Barclays UK and Barclays Corporate & International, a couple of things jump out of the Q1 numbers. Barclays UK return on tangible equity was 20.5% – that’s not 10%, it’s not 15%, but over 20%. This is a very powerful franchise in a market with low rates.

“The second one is the importance of the cards business, merchant acquiring and corporate banking. Both in the US and Europe, we have a great portfolio of consumer businesses outside the UK.”

Staley notes that while investment banking attracts much discussion, market risk and counterparty credit risk within the division accounted for only 13% of group risk-weighted assets at the end of the first quarter of 2016. That said, it is categorically not being downgraded.

“We are not betting the proverbial farm on the IB,” he says. “The flipside is that even at 13%, because we are one of the largest banks in one of the largest economies in the world, we have enough capital to be a tier-one investment bank. And that’s what we are going to be. My experience is that the rewards in the IB space accrue to the tier one players.”

What makes Staley think that he is on the right path? First and foremost, the core businesses – Barclays UK and Barclays Corporate & International – are working well. Analysts are certainly giving him the benefit of the doubt for the moment. “Nearly half of group income currently stems from strong franchises in UK retail and business banking and credit cards,” wrote Pauline Lambert of Scope Ratings in the wake of the bank’s first-quarter results.

“The size of the investment banking business, which had been reduced to about a third of group RWAs, is expected to remain relatively unchanged going forward and contribute to earnings diversification. While performance is likely to suffer over the next two years, this reshaping combined with the run-down of non-core assets should enable the group to generate long-term sustainable earnings.”

Non-core is not the only thing dragging down group ROTE: the investment bank only clocked up 7.3% in Q1. Staley has frequently spoken of the structural problem that the investment banking industry has in not covering its cost of capital. Fulfilling his ambitions will mean overcoming that problem.

This is not a great market in which to be looking to grow revenues, and some of the improvements will have to come from securing market-share gains from competitors – something that is also at the heart of the CIB strategy at BNP Paribas, for example.

Happily for Barclays, it looks like it is already happening. This time last year the bank’s market share of EMEA investment banking fees, according to Dealogic, was about 4%, giving it a seventh place ranking. Now it is above 5%, giving a ranking of fourth. It is a slow climb, but that is against a backdrop of total IB fees earned by the current top 10 in EMEA falling almost 30% year on year. Those whose market share has fallen are Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank.

European (and Asian) equities and equity capital markets was one of the great post-Lehman projects for the bank, the intention being to bring its offering more into line with the US franchise that it had acquired from Lehman. But building that asset class is about much more than just coverage – which is why M&A can show quicker returns. With equities the infrastructure requirement is substantial.

Even those who have worked in the Barclays equity franchise admit that it has grown in fits and starts. Recognizing that it could not build sufficient scale in Asia, the bank has now put a lid on its equity ambitions there.

But there are bright spots. Although the bank only ranks 10th in EMEA ECM so far this year, its market share of about 4% compares well with the 2.5% it saw a year ago. And it is not just UK mandates. At the time of writing, the bank was involved in two current Spanish IPOs, Parques Reunidos and Telepizza.

In investment-grade DCM the bank has always been strong. Its market share is currently flat from the previous year, at 7%, putting it in third place after HSBC and Deutsche Bank. In high yield, its share has risen from 6% to 8%. Credit was a great performer for the bank in the first quarter of 2016; most rivals saw their FICC revenues fall anywhere between 10% and 40% year on year, while at Barclays they rose 2%. But this relative outperformance is easily explained: the bank carries much less inventory now than it used to, meaning that any substantial widening in credit, such as that which took place in February, hurts the bank less than its peers. Conversely it will benefit less from rallies.

Relief

Overall, the tone from bankers at the firm is one of relief that there is a commitment to do more than just retrench. “For lots of us in the business I think the feeling is better now than it has ever been,” one banker tells Euromoney. “Management seems coordinated, it knows what it wants to do – and there is lots to do.”

Staff say that for the period in 2015 when there was no CEO there was a tendency not to complain of frustrations, with an understanding that the situation was difficult. Now that there is an almost-complete management bench, there is more impatience from the rank and file.

Barclays bankers are still waiting to see exactly how the new organization of the investment bank will play out beneath whoever is appointed to run the Corporate & International division – the last of the senior management roles still to be filled after the departures of Tom King and John Winter.

That the bank is planning an external appointment is notable for its rarity at the moment. Speak to any senior Barclays investment banker and it won’t be long before the subject of the hiring freeze comes up. The freeze was put in place by Staley soon after joining. There is nothing particularly revolutionary about the policy, but it has made waves internally nonetheless. Headcount in the investment bank fell from 20,500 in 2014 to 19,800 in 2015, but the bald number does not tell the whole story.

“He wanted to get it under control, and I can tell you it has made a dramatic difference,” says one business head. “You know what it’s like at most of our places: you lose a French coverage guy and the first response is to hire another one from somewhere. But there’s no real reason why that should be the best option.”

Graduates are still being taken on, but broadly speaking other external hiring has stopped. There have been exceptions, of course, although it is worth noting that the appointment in March of Carlo Calabria as chairman of EMEA M&A alongside some of his colleagues from his CMC Capital boutique had been under discussion for a long time and had been all but worked out before the hiring freeze kicked in.

In the US this year, the bank has hired Jason Haas and David Levin from Deutsche Bank for healthcare coverage as it looks to build up its presence in the sector again after a poaching spree by Credit Suisse in 2015. Eric Biddle has joined to cover retail and consumer names from Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Happily for Staley, such hires are not (for the moment) being seen internally as evidence of inconsistency of policy, but rather as a sign that he has a sensible pragmatism about him. Dozens of internal appointments and promotions have been made. One that came just before the freeze, but which is cited as proof of how well internal moves can work, was that of Pier Luigi Colizzi as head of EMEA M&A last July. He was previously the head of banking for Italy. Gavriel Lambert moved in November from Barclays in the US to head the EMEA consumer retail group. When Walter Cumming retired this year, Tom Wilkinson was promoted to replace him as head of oil and gas.

For situations where an internal move is simply not possible, external hiring can be done – but the bar is set high. “You can’t solve everything internally, and for those times Jes has said that you need to come and make a case for an external hire,” says the business head. “If there is a strong economic rationale for doing so, then it can be done. It’s hard to argue against that approach really. We’ve had discipline forced upon us and the result is that we are making the most of the people we’ve got.”

One side-effect of a greater reliance on internal resources may be to make cooperation stronger. One priority as Barclays looks to raise its game must be achieving better coordination between the corporate bank and the investment bank. Firms like HSBC, Citi, and, yes, JPMorgan again, have preached the same mantra for years.

“The feeling within the bank is that there is a lot of juice to be found in this coordination,” says a senior banker. “JPMorgan has done it, so it’s not as if Jes hasn’t seen that movie before.”

More with less

This matters because it will define the future shape and success of Barclays once the current tasks of reducing non-core RWAs and cutting costs are more or less complete. Cost-cutting is understandably one of the priorities now, but Barclays bankers know all too well that cut too aggressively at the producer level and a bank loses the ability to earn its way out of a downturn in activity and suffers heavily relative to peers as business picks up. Better linking of investment banking activities to a firm’s corporate and institutional client base ought to ensure that it can do more with less.

UBS is an example of a firm that has shrunk its focus to those franchises that can support its private banking and wealth management franchises. Staley is retaining a very broad offering in terms of product but is tailoring the firm to the needs of those clients for whom the UK and US markets are key.

There is another trend that could well support the bank in the medium term. Bankers across European banks consistently talk these days of clients being worried by the fading of some previously prestigious European investment banking franchises, most notably Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse.

The challenges remain immense. Legacy conduct issues will continue to dog the firm, new ones could emerge, regulatory changes could wrong-foot it, non-core disposals could hit stumbling blocks, the US franchise could falter.

Is Staley cutting too far, or in the wrong places? He does not want to bet the farm on the investment bank, but one obvious danger is that his cuts elsewhere might mean that he ends up doing just that. And what of his ability to execute in the way that he sees fit? So far he has been given latitude, but McFarlane has already ditched one CEO.

Staley knows all this, but thinks his explicitly transatlantic strategy will stand him and the firm in the best stead in changing economies. “One of the realities coming out of the financial crisis is that the regulatory response means that economic growth will be financed through the capital markets, not through bank balance sheets. This is one of the structural evolutions,” he says.

“Users of capital will find the providers of capital, and to play a part in that you need to have the right reach. You want to have bankers in the field, of course, but you need to be firmly positioned in the two big centres of London and New York. Through those two cities you can connect with users and providers of capital and our presence is a great competitive advantage for Barclays.”

That is doubtless true, but all the analysis in the world will not buy him more time to fix returns. Restless shareholders will hold him to his ambitions and competitors will try to thwart him. And he needs to keep clients onside: his reputation for giving time to this aspect of the job will stand him in good stead.

Staley is aware of the pressure as much as anyone. “It is time to finish the job,” he told shareholders at this year’s AGM. “You have been patient long enough.”