Roberto Sallouti was running on his treadmill at his home in São Paulo in the early morning of Wednesday November 25, 2015, when his mobile phone buzzed, out of his reach. The then senior vice-president and board member of BTG Pactual maintained his pace. It was only when the phone continued to buzz angrily over the next minute or so that he looked at it. There were many missed calls, including quite a few from the bank’s front desk. He returned the call.

“The federal police are here, lots of agents,” he was told.

Sallouti assumed the unannounced visit was in regards to a client matter – as the leading bank for Brazil’s richest families, legal issues tended to crop up from time to time. He switched off the treadmill, hoping to be able to resolve the matter and clear the bank’s reception of police agents before the office began to get busy for the day. But before Sallouti had been able to leave for the bank’s headquarters in São Paulo’s Faria Lima district, he got a call from one of the bank’s lawyers.

The news was blunt: “André has been arrested.”

Huw Jenkins was sitting at his desk at the bank’s London office in Berkeley Square, two hours ahead and almost 6,000 miles away from the Brazilian HQ, when he received a call from Marcelo Kalim, senior vice-president and a member of the board. He in turn had been notified of Esteves’ arrest on arrival at Lugano’s airport.

The call was brief, sparking many more calls for each to make: “You’re never going to believe this…” Kalim began. Afterwards, Kalim cancelled all his meetings in Switzerland and headed straight back to São Paulo.

It’s funny, but this whole repositioning has made our clients happier, our employees and partners happier, and our counterparties happier – Roberto Sallouti, BTG Pactual

Meanwhile Jenkins, who was then vice-chairman of the board of directors, got on the phone to Sallouti and board member, Pérsio Arida. By 10am local time Sallouti says, the confusion was beginning to clear a little. By watching local TV and reading the newspapers’ websites, they had established some basic facts, as leaks to the local media had become a regular part of the arrest process and a faster route to the cause of arrest than official channels.

They learned that André Esteves, the bank’s chief executive, controlling shareholder and figurehead, had been arrested for allegedly obstructing justice after Delicidio Amaral, leader of the then ruling Workers Party in the Brazilian Senate, was recorded attempting to bribe an ex-Petrobras official not to sign a plea-bargain agreement with investigating authorities. The recording, which was made public to local media, was made by the son of Nestor Cerveró, the former director of international operations at Petrobras.

In the recording, Amaral was heard offering to help Cerveró escape to Spain via Paraguay, as well as a stipend of R$50,000 ($15,650) a month, in return for Cerveró’s silence; Amaral also referred to Esteves as a channel for these payments. The authorities also claimed that Esteves had an illegal copy of Cerveró’s previous testimony and was seeking to suppress information about bribes a petrol distribution company that some bank partners had invested in had allegedly paid to former president Fernando Collor.

It also transpired that Esteves’ arrest was valid for five days and was necessary, according to the Supreme Court, to allow for a search of his offices. After that it would need renewing and, unless evidence was produced in the interim, the consensus legal view among those advising BTG Pactual was that he would be released; there was no direct incriminating evidence.

Plan for the worst

Nevertheless, while hoping for the best, the bank’s senior management began to plan for the worst. Arida was proposed as acting CEO as his background as a former governor of Brazil’s central bank would be a valuable source of credibility with the regulators and the markets in the coming days. His first meeting at the central bank was 2pm that afternoon; many more were to follow. The proposed new management structure was approved at a hastily convened board meeting early that evening.

The bank also established four war rooms, one each for communications (client and media), liquidity, regulatory relations and legal.

“This all happened on the Wednesday and went into Thursday and Friday, but we all thought that the arrest was a mistake and he would be freed at the weekend,” says Sallouti. “And that was, to some extent, also the working assumption of our clients. Yes, we had some withdrawals, but this wasn’t the heaviest period.”

The bank still activated contingency plans, underpinned by a couple of decisions that would prove to be crucial. The first was to communicate to clients that BTG Pactual would put up no gates, nor frustrate any attempts to liquidate positions clients held at the bank.

Sallouti outlines the philosophy behind this first position: “We took the view that it’s the clients’ money – we are just the fiduciary agent – and if they want an explanation, they will get one. If they want to talk to someone senior, they will do so. And if they want their money, they will get it.

“There will be no threats about not providing service if they withdraw funds. On the contrary, let’s give them an even better service so that clients will come back when things are clarified. No gates.”

Jenkins saw the impact of this decision better than anyone.

BTG Pactual’s Global Emerging Markets Macro Fund (GEMM) was managed in London. Not only did the bank not put up gates but it actively facilitated redemptions: investors had the opportunity to redeem once a quarter but were required to provide three months’ notice. The redemption deadline for liquidating at the next possible opportunity was December 1.

Rather than holding its breath and hoping for minimal notifications at the beginning of the next week, the bank decided (and communicated to investors) on November 27 that it would extend the redemption period until December 15 (it extended it again until mid-January) to provide clients with time to evaluate the decision.

“It was a very sensible decision and gave us time to move the fund to liquidity in an orderly manner,” says Jenkins.

Severe redemptions were still to come (in the case of GEMM, assets under management collapsed in a couple of months from over $5 billion to $150 million), but the decision was taken to provide at least the hope of longevity.

|

|

|

Huw Jenkins, |

“If we started to tell clients that we can’t return money to them – or that we can’t meet our obligations as they became due – then we’re not going to have any business left at the end of this,” says Jenkins.

The other crucial decision was that the bank took an extremely conservative approach to liquidity management. The interim management decided to plan for an eventuality where all maturing liquidity wouldn’t be renewed. It assumed, Jenkins says, that “everything was going away” and so redemptions would have to be funded from the bank’s own resources.

This premise naturally led the liquidity war room to work in the direction of a very extensive and rapid plan to liquidate everything it could in the short term and to begin exploring the possibility of liquidating less liquid positions. That work began on November 25 and would see the bank liquidating assets worth almost R$50 billion ($15 billion) over the next three months.

Meanwhile in employee and client communications, the bank tried to stress that the charges related to Esteves and not the bank. That message, however, was not easily made, given that Esteves was seen by many as the personification of BTG. Looking back a year later, Sallouti concedes that this strategy contained dangers that the bank ignored for reasons of expedience.

“I think it had always been convenient for the bank to have André as its public face. To some extent that was [the other senior bankers’ fault] because we loved to be anonymous. But while it was convenient, it wasn’t the best thing in this situation,” he says.

That situation was a key-man stress test so severe it would threaten the bank’s viability. In its struggle for survival, the bank would irrevocably be transformed in size and shape.

Hammer blow

On Sunday, November 29, 2015, Esteves received a hammer blow. In the morning, his five-day stay at the notorious Bangu 8 jail on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro was extended indefinitely when the Supreme Court approved a motion to change his arrest to ‘preventive’ status.

Just as he was struggling with the fact that he faced an uncertain – and possibly lengthy – period of incarceration, his lawyer arrived with a letter from his oldest colleagues – people he has long considered among his closest friends. It was his resignation letter. And his signature was required.

In the lead up to BTG’s 2012 IPO, Esteves had approved a governance rule that outlined contingency plans in case something happened to him. Key-man risk was one of the clearest issues for investors in the BTG Pactual equity offering, so the rule set out what was to happen if he was killed or injured. The key-man risk clause never envisaged that he would be unable to execute his function as CEO because he was in a federal prison. As such, the wording centred on what would happen if Esteves was “no longer an employee of the firm”. To activate the clause that would automatically change Esteves’ controlling voting shares to a passive equity holding required Esteves’ resignation. And quickly.

“Imagine, you’re sitting in Bangu 8 and your lawyer comes in to say that your colleagues want to take control of the bank from you,” says Jenkins. “He was sensible and cool enough to know that this was the right thing for them to do to be able to get on and run the place.”

Esteves signed and the seven partners with the next largest shareholdings (Kalim, Sallouti, Arida, Antonio Filho, James de Oliveira, Renato dos Santos and Guilherme Paes) assumed control. Arida became executive chairman. Jenkins became vice-chairman, while Kalim and Sallouti became joint CEOs. With these permanent changes it had become clear, for the benefit of anyone who had previously doubted it, that BTG Pactual was about to feel the full force of a reputational crisis of confidence.

Three objectives

The new management had three clear objectives: generating sufficient liquidity, communicating reassurance to clients and rebuilding its credibility.

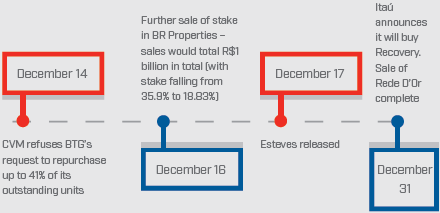

The explorations of its liquidity options made in the previous week were now put into full operation. It sold more than R$10 billion of credit portfolios to local banks and began negotiations of other non-core financial assets – such as the December 31 sale of Recovery to Itaú for R$1.2 billion. The team also tasked its own investment bank, headed by Paes, to begin divesting its own portfolio of what Sallouti calls “principal investments”.

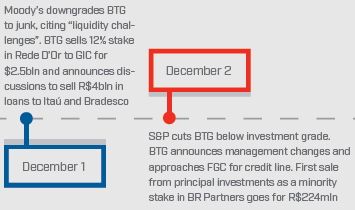

BTG agreed to sell its 12% stake in Brazilian hospital chain Rede D’Or to GIC, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, on December 1; the deal was finalized on December 31. GIC had been a partner in the original deal and therefore knew the company well – there had already been discussions about BTG selling its remaining stake and so due-diligence requirements were minimal.

Finally the bank calculated it would have to liquidate one of its three main strategic investments: its commodity business, its recently acquired private bank BSI, or its Latin American banking investments.

Meanwhile, the bank was facing a serious run because of a lack of confidence in its ability to survive. On Thursday December 1, Moody’s acted suddenly, cutting the bank by three notches to below investment grade. The next day Standard & Poor’s followed suit. Rumours swirled around the financial sector about redemptions and crashing AuM. Although the bank’s new management team was confident it could liquidate assets quickly enough to deal with expiring credit facilities or to meet client redemption requests, the bank was in trouble.

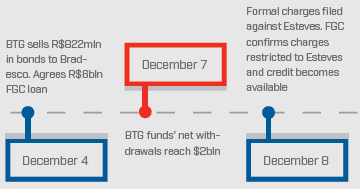

By Tuesday, it was clear to the management team that it needed to apply a firebreak to try to stem the loss of confidence. And so, on the same day as S&P’s downgrade, Arida went to Brazil’s deposit insurance fund, the FGC, for a loan to prove to the market its liquidity position was under control.

Those negotiations took two days – a short time, especially given the complication that BTG could not easily use any assets that it might want to sell as collateral for the loan. In the end, the seven controlling partners put their entire personal wealth up as collateral. Their wives were also required to sign. Professional survival suddenly became personal.

“Even my dog would have been available [to the creditors if we didn’t repay the loan],” says Sallouti.

But the FGC loan was critical.

“It bought us the time to implement our strategy,” he says.

An equity analyst who covers BTG Pactual points out that: “Banks either go bust in the first two weeks of a crisis or they don’t. So in that sense, I’d agree that the FGC was probably when a line was drawn and a collapse became unlikely.”

Sallouti says: “The Thursday we got that line [from FGC] was for me when I thought: ‘OK, now we don’t have a liquidity problem. Now we need to get the reputation back.’”

The FGC credit line was an attempt to cauterize the bank’s wound but, help as it did, the bleeding continued. The post-crisis share price bottomed out on December 11 at a close of R$13.75 down 55% from a pre-arrest close of R$31. The bond performance also showed highly distressed levels – trading at around 55 cents to the dollar.

By that stage bank clients had withdrawn a net R$7.6 billion from the 10 fixed income funds listed on BTG’s website. Other assets under management were redeemed; Exotix estimates that in the three months following the arrest of Esteves, total outflows were R$34 billion, with a further R$14.9 billion in deposit outflows making a combined total of R$48.9 billion.

The bank knew it must restore its reputation if it were to staunch the outflows.

Reputational rehab

To start the bank appointed Jenkins – the bank’s leading non-Brazilian national and therefore perceived by the market as unlikely to be tainted by domestic issues – to head an investigative special committee. This was tasked with looking into the accusations of misconduct and corruption against both Esteves and BTG Pactual. The committee was also led by independent board members Mark Maletz and Claudio Galeazzi; they hired international law firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan and local law firm Veirano Advogados.

|

|

|

|

Quinn Emanuel’s team was headed by William Burck, who had led the investigations into bribery at Enron and Fifa. He immediately gave the investigation a sense of credibility and independence.

The investigation also brought in forensic auditors from KPMG and PwC. The preliminary results gave KPMG sufficient comfort to sign off on the bank’s accounts in early February with an unqualified audit opinion.

“We not only needed to have financial rehabilitation, which was focused on liquidity, but we also needed to have a reputational and governance rehab – we needed to demonstrate to the world that there had been no wrongdoing,” says Jenkins. “Although we didn’t have access to André, we had access to his lawyers and through them he answered all our questions, despite there being a delicate possible conflict of interest. And once we had this comprehensive picture, we asked Bill [Burck] how we compared to Enron and Fifa. He said: ‘If you go from zero to 10 – you are a zero. I have never seen a situation where an institution that relies on public trust has been brought into such jeopardy based on zero evidence. If you look at the documentary trail, there is just no evidence of malfeasance anywhere in the company.’”

However, in the market there are lingering suspicions and doubts that centre on Esteves’ reported close relationship with Eduardo Cunha who was speaker of the congress and was in charge of much legislation that benefited BTG Pactual, such as the removal of the restriction on the sale of healthcare companies to foreign owners shortly before the sale of Rede D’Or.

While there may not be any documentary proof of corruption, some wonder if Cunha – now himself in a federal prison – may attempt to enter a plea bargain and in doing so provide testimony against Esteves.

“We looked into everything, and we can find no evidence of anything untoward,” says Jenkins in response to this question. “Our expectation is that he won’t have anything to say in his witness statement. Obviously if he does, we’ll have to look at that on its merits, but as far as we can tell there is nothing that gives us any pause for believing that there was anything that gave us an informational advantage to do anything other than you would normally do as a bank when dealing with regulators.”

Back in December 2015 though, the bank had to put on a brave face. Rumours that it was teetering on collapse were rife and Jenkins remembers these doubts were circulating when he and Arida went to the World Economic Forum meetings in Davos in mid-January.

Jenkins says: “We did the rounds and were assiduous in meeting with all the main investors and counterparties to assure them that we had the liquidity issue in control. I think that gave a degree of comfort that we were going to survive.”

He also says the support of the Brazilian financial system (the FGC is backed by the big banks and the loan required their approval) and helpful comments from key players such as then president of the central bank Alexandre Tombini (who also attended Davos) helped prevent the situation from spiralling out of control.

Despite the fact that the bank has not released the full report (Quinn Emanuel did issue a press release of its core findings and conducted a press briefing in São Paulo), Sallouti argues that Nelson Jobim’s decision to join the bank as head of institutional relations and compliance policies is an endorsement of the bank’s clean bill of health.

Jobim was previously a government minister and chief justice of Brazil’s Supreme Court.

“He now has – like us all – unlimited liability to the bank, so he of course did his due diligence and accepted that there was no wrongdoing,” says Sallouti.

That liability, however, only begins from the date of joining, July 26, 2016. It is not retrospective, so would not cover anything that happened before that date.

“If we hadn’t been able to get the accounts signed off – or if there had been some issue that had made KPMG uncomfortable – I think we would have been in deep trouble,” says Jenkins. “So when we got the clean audit report in late January I thought we were past the worst. We might have to rebuild our business – that’s the next challenge – but it was then clear to me that we were not going to fail.”

Liquidity challenge

While Jenkins busied himself with restoring the reputational credibility of the bank, the liquidity challenge continued. The bank sold credit portfolios to Itaú and Bradesco in early December. On December 31, it sold its debt-collection firm and delinquent credit portfolio for R$1.2 billion. Fast progress was made on less liquid assets: on December 16 BTG sold part of its stake in BR Properties; Rede D’Or went to GIC for R$2.38 billion; and the bank put up its stake in Pan Seguros up sale.

Despite clearly being a distressed seller, BTG was able to avoid a firesale and conduct a competitive bidding process for its assets. That was in part due to the fact that it had a good portfolio that had been conservatively valued. A lot of the proprietary assets were sold at a profit.

“It just shows the execution capacity of the investment bank team,” says Sallouti.

The financial assets were also conservatively marked, while the quality of the bank’s back office systems and management is also noteworthy. It is one thing to agree a price for R$12.5 billion in credit, but it is quite another to complete the settlement process.

|

| BTG Pactual CEO Roberto Sallouti |

Sallouti says the bankers worked three nights in a row: “It shows that all our documentation was impeccable and our credit analysis was thorough – otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to sell in that space of time.”

The bank’s remaining strategic decision was whether to sell its Latin American business, BSI or its commodity business. The sale of the Latin American banking assets was quickly discounted – those were deemed too core to divest and too important for the bank’s future business strategy. The phrase used was “protect the fortress” and for BTG Pactual, Latin America is its home market.

Meanwhile, selling the commodities business would have perhaps been problematic; it had a relatively short track record and valuations were not high. The commodities business, Engelhart, was eventually spun-off to shareholders (BTG retains 35%) to lower the impact of regulatory requirements and earnings volatility on the core bank. That left BSI.

Jenkins flew to New York in early December and hired Lazard to work on its sale. Steve Jacobs, a senior BTG banker based in London, was relocated to Zurich for three months to work on the sale. BSI was sold to EFG at the end of February 2016, with BTG retaining a 30% stake in the combined entity.

“We think the deal makes a lot of sense for EFG – it has a very complementary fit with BSI and it will be very accretive – and we have effectively kept an option on the upside in our equity participation,” says Jenkins.

As the bank worked through its liquidity challenge – some of which took time to come to fruition (the bank announced the sale of Ariel Re in November 2016) – the redemptions slowed. But when the dust settled, its balance sheet was one-third the size of a year previously. The majority of that reduction came in the first three months of 2016. In January, the leadership went back to the board to approve a plan to cut costs. In February and March, global headcount was cut by 25%. In some places the cuts were much deeper, as high as 50% in the London office.

“It was tough. We had sold people a story of growth and opportunity,” says Jenkins.

“It was the most difficult part,” says Sallouti. “But we had to adapt to the new reality. And, actually, this cut of 25% wasn’t to fit the size we had become but anticipated the growth to come and to preserve the quality of our team. In March, we still got ranked number one in all sectors in equity research by Institutional Investor. In March we were in the dumpster! But all our research analysts, all our senior traders, all our senior bankers were all still here. That’s what surprised a lot of clients.”

No pressure

There are still a couple of assets that might be sold: Petrobras’ Africa portfolio and Banco Pan. The bank has previously said that both are conservatively valued on its balance sheet; it is under no pressure to sell either of them. However, the rest of the divestitures have pushed the bank’s Basel III capital ratio to 20%. That is solid, but it makes it harder to deliver the high returns on equity of previous years.

Sallouti, who on November 9, 2016 became sole CEO (Arida remains on the board), says BTG is the most capitalized and liquid bank in the Americas and it will remain so in the near future.

“The ratios are very high and that will continue in the short and medium term,” he says. “We sacrifice profitability, but it is important in the short run to have a solid business. As well as excess capital we also have lots of operational leverage. We can double AuM in wealth management and asset management with minimal cost. We can increase IB by 50% without adding any people. We can also return to the portfolio we had in corporate lending with minimal additional costs. Growth will come from AuM recovery and Brazil recovering, as well as a new growth strategy in Mexico and Argentina.”

The BTG Pactual of 2017 is now very close to the BTG Pactual of 2012, before the rapid expansion added new businesses and new risks. There are now five main businesses: investment banking, sales and trading, corporate lending, asset management and wealth management. Principal investments or private equity will no longer be pursued “other than for seed money for client ventures,” according to Sallouti.

The Latin American connection is already providing growth. AuM and the bank’s market share in equities in Mexico and Colombia are now better than a year ago. Sallouti is excited about the potential of Argentina – he sees similarities between Argentina now and Brazil in the 1980s. Mexico, too, is still an opportunity for further expansion, but it is a more competitive market and more mature.

|

The bank’s model is still evolving. It recently launched BTG Pactual Digital, its bold bid for a 10% share of the R$650 billion market for the management of the money of the affluent retail sector. This is a new venture targeting a completely new customer segment.

As BTG deploys excess capital in sales and trading, and AuM increases in the asset and wealth management business, the bank believes ROE will increase. It points out that the firm’s principal investment activities were detrimental to ROE.

Sallouti says recent growth has been rapid: “Every month it accelerates. Today, things are better than I expected – it really is exponential – and it is back to normal in the sense of being within the new strategic form that we have.”

That return to a model of a Latin American investment bank, with a more stable and less risky business model, is being seen as a positive. Meanwhile Esteves has quietly returned to work as a senior partner focused on advising on “strategy and supporting the development of its activities”. The prosecutors have not dropped the charges against him.

However, the leadership remains unchanged. Esteves was not available for interview for this article – one of the main reasons the bank participated was to illustrate how it managed in the immediate aftermath of his arrest and its recovery to date. Questions about his potential return to leadership are batted away with: “You’d have to ask him.” But with charges still pending, the leadership question is moot anyway.

“You can’t turn back the clock, so he has had to adapt to a different role, a different profile,” says Jenkins. “But this is an extraordinary man. He’s the smartest guy I know, the hardest working, one of the most charming and, it turns out, the bravest. You just have to say it’s amazing that he made the right decision on that Sunday in jail and he has made the right decision not to try to jump back behind the wheel, but to recognize that his situation has changed. But he is still the founder, a fantastic strategic thinker – and incredibly helpful.”

The bank is now far beyond the point where it was embodied by Esteves and that is definitely to its benefit. In becoming smaller, it has become much bigger than any of its individual bankers.

“It’s funny, but this whole repositioning has made our clients happier, our employees and partners happier, and our counterparties happier,” reflects Sallouti.

Jenkins says: “Everything that could have gone wrong from an external point of view went wrong. But on the other side of the coin, everything internally worked as well as we could have hoped: the marks on the book, the speed of reaction, the alignment of interests and the behaviour of the people.”

BTG Pactual suffered a real-life stress test. The investment bank, with arguably the highest key-man risk, got hit right on its weak spot. One analyst argues that the bank would have been in a better position if Esteves had died – at least it would have garnered some sympathy.

Runs on banks are usually something endogenous: a failure in the balance sheet, a big piece of litigation or regulatory oversight. But in BTG’s case it was arguably exogenous. There was nothing wrong with its balance sheet – it was just an aberration that occurred to one of its senior executives. Its most senior executive.

And after so much value was destroyed on a piece of hearsay (Esteves’ name being used in a context that could easily be argued was done to make the speaker seem more credible) and with no actual proof of his complicity in any attempt to bribe Cerveró, what are Jenkins’ and Sallouti’s thoughts now on the damage wrought to BTG Pactual?

“The truth of the matter is that we all hang by a thread, and that thread is your reputation. You can’t afford to take risks with your reputation,” says Jenkins. “There is little point in ascribing blame. Whether it was André being arrested or there being a problem in the loan book, you recognize that these institutions have to be very, very prudent.

“We had a fantastic run, we probably expanded a bit quickly on too many fronts and we didn’t necessarily control things as we should have done. Going into direct investment on the scale we did was probably over-ambitious with the benefit of hindsight – not that financially we made terrible decisions. But if you look at what the merchant banking strategy brought with it in terms of exposing financial institutions to governmental relations and unregulated subsidiaries – and all of the things that went with it – it was probably too much.”

Sallouti sees little point in looking back. “We just have to get on with it,” he says.