|

By the beginning of 2020, the often long-haired and bearded founders of a clutch of mass-market neobanks had become the new masters of the universe in European financial technology.

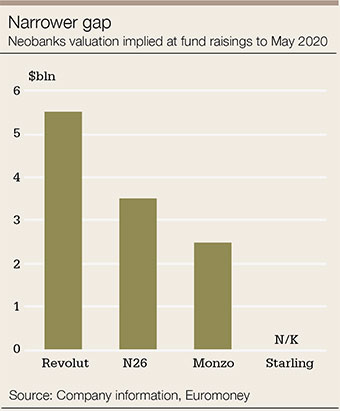

Valuations in recent funding rounds had made them worth as much as incumbent rivals with hundreds of billions of dollars of assets, not to mention centuries of history.

The neobanks had faced concerns about their capacity to stop small-time money laundering and about worryingly high senior management turnover. They seemed unstoppable.

Then, within a few days in March, as the coronavirus lockdowns spread across the continent, their ambitions to rapidly match and even surpass global retail banks suddenly became much harder to achieve.

The race is still on to reach 100 million clients globally within the next few years. Europe’s top four neobanks are all involved in expansion plans elsewhere on the continent and in the US. And most are still targeting IPOs worth tens of billions of dollars in a few years – although none are profitable yet.

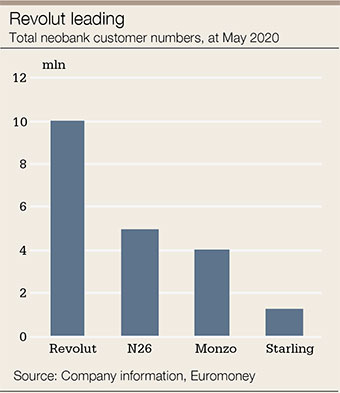

UK-based Revolut is ahead on customer numbers, with about 10 million. Germany-based N26 is similarly determined to get to 100 million globally. It has about five million now, compared with around four million at Monzo, which is mainly active in the UK. Starling Bank, also UK-focused up to now, has about 1.3 million clients, although its deposit balances tend to be larger than rivals’.

Banks and fintechs that have not received enough funding for the next 18 months or two years will be in trouble – Markos Zachariadis, Manchester University

The idea of reaching as many as 100 million clients is tantalizing for the fintech industry, as it would take away the distribution advantage that the incumbent banks have previously had. They would achieve this, moreover, at a time when forward-looking big banks – such as BBVA and ING – want to become more like app-based platforms that can be used to sell both their products and others’, which is essentially what the neobanks have developed.

“Our growth numbers are unprecedented in banking,” says Georg Hauer, N26’s general manager for the German-speaking countries. “The potential is huge, and outside Europe the potential is even bigger. We have a product that serves a global need.”

But after years of easy access to cheap funding, those that follow the sector say the neobanks face a watershed moment similar to the bursting of the dotcom bubble. A few, perhaps only one or two, might have enough capital to benefit from an accentuated structural shift to digital banking in the 2020s. Others will wither, fail or get taken over.

In one possible sign of the direction that European neobanks might take, coronavirus-related funding pressures forced US-based Moven to ditch its consumer business in March. It is now focusing on providing its financial wellness technology to other mobile banking firms, in other words banking as a service.

“Banks and fintechs that have not received enough funding for the next 18 months or two years will be in trouble,” warns Markos Zachariadis, fintech professor at Manchester University. “There’s not enough funding right now. Investors are looking to liquidate their positions. They’re not necessarily looking to invest in startups because of the uncertainty.”

If you compare us to the big banks, their distribution is too complex; they have too many branches… They have tech that needs replacing, and they can’t afford to do so – Anne Boden, Starling Bank

Europe’s retail neobanks have already moved on from being mere electronic money providers. They have all acquired banking licences, starting with Starling in the UK in 2016 and ending with Revolut in Lithuania in late 2018.

Yet proving a viable business model has still been hard, not least because they do very little lending, especially on their own balance sheets. Growth of customer numbers rather than earnings has determined their valuations until now.

Moreover, tech founders naturally try to keep control by raising as little capital as possible before a bigger round at a higher valuation after a year or 18 months of operation.

The survival of weaker neobanks as independent firms might therefore just depend on when they completed their last funding round.

Funding pressure

Financial pressures are all the more intense now due to the impact of lockdowns and travel bans on interchange fees from Mastercard and Visa, especially on foreign currency payments. Revenue from subscriptions to their bells-and-whistles premium accounts, let alone credit, was only just getting started.

Monzo was rumoured to be halfway through a fundraising when the coronavirus hit. Chief executive Tom Blomfield even had to go on Twitter in March to say the firm was not going bust. He has ditched his pay for a year and offered a fifth of its staff temporary paid unemployment under the UK government’s furlough scheme.

Amid reports that Monzo’s fundraising would come at a 40% dip to its valuation at its last funding round in mid-2019, Blomfield announced in late May he will make way for a new CEO, former Citi banker TS Anil, while he will become president.

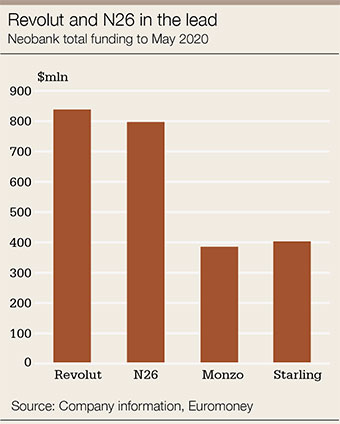

Revolut and Starling, by contrast, completed funding rounds in February, with Starling also tapping investors in May.

Revolut’s $500 million valued it at $5.5 billion, more than any other neobank globally except Brazil’s Nubank. Revolut is even more dependent than Monzo on travel money.

Nik Storonsky, CEO of Revolut

Neobanks rely heavily on social media for their marketing, which can be a double-edged sword. Revolut had to issue a statement in late March from its chief executive, Nik Storonsky, in response to “rumours and false information” drawing attention to its capital raising, to say it was “business as usual.”

Revolut, in fact, still aims to be “the first truly global bank”, according to its head of business Vaidas Adomauskas.

Nevertheless, as a result of the coronavirus crisis, it is cutting costs. Its founders have forgone their pay for a year, senior management have taken a pay cut and others are being offered the opportunity to swap their salaries for share options on a two-for-one basis.

N26, meanwhile, is “not at all worried” about the impact of the coronavirus crisis on its funding, according to Hauer.

N26’s investors issued another €100 million of series-D funding in early May, adding to the €170 million raised last July and €300 million in January 2019, in a round that has valued it at €3.5 billion. Its backers include Singapore sovereign wealth fund GIC and Allianz X, the digital arm of the German insurer.

During the initial shock of the coronavirus outbreak and lockdowns, Hauer admits, people had other things to worry about than opening a new bank account. Client acquisitions and transaction volumes have since rebounded, he says, and the long-term behavioural effect of lockdowns will expedite its growth.

At Starling, growth in client numbers has risen in business banking since the lockdowns, although the numbers have slowed in retail. That’s partly thanks to a UK government grant to expand in small and medium-sized enterprises and to its launch of television advertising in February.

Anne Boden, CEO of Starling Bank

“We have the platform and the money to take it to the next level,” chief executive Anne Boden tells Euromoney. “I think we’ve got a long way to run yet. The big banks are going to be shocked by us taking real market share.”

However, the reality is that venture capital investors were already losing patience and starting to push some neobanks to focus more on revenues and profits months ago. Storonsky publicly acknowledged as much at the time of Revolut’s capital raising in February.

After the coronavirus, these demands will not only be more acute they will also be much more difficult to satisfy because of the macroeconomic environment.

UK neobanks tripled their customer numbers to almost 20 million in 2019, according to Accenture, before the growth started to slow in the second half of last year.

“The attitude of private equity investors is shifting,” says Mike Harding, a partner covering fintech industry at Oliver Wyman. “They’re saying: ‘We’d like you to shift to profit faster as our thinking about the long term is different.’ Since the coronavirus, those discussions are becoming much more intense. That will change the rate of growth and the international ambitions of the neobanks.”

Fintech stocks fell even more than the wider US market during the early 2020 market crash, according to Rosenblatt Securities. To the extent that this translates to unlisted neobanks in Europe, existing investors may prevent them from issuing equity at lower valuations, so-called down rounds. It could make it hard or impossible to gain the funding for the international economies of scale on which they have staked their futures.

Until now, neobanks have been all about cheap and better-engineered digital products that can rapidly gain scale in multiple markets in terms of customer numbers, even if their deposits and – especially – loans lag well behind.

We want to have the best product out there because we know that with the best product we get the highest number of customers and the happiest customers. The rest is just a consequence of that – Georg Hauer, N26

N26, above all, shows little intention of turning its attention to profit before it has reached what it regards as its full potential.

“The more customers we win, the closer we get to the break-even point,” says Hauer. “We want to have the best product out there because we know that with the best product we get the highest number of customers and the happiest customers. The rest is just a consequence of that.”

But growth strategies based on cost and technology need capital, particularly when so many rival banks are copying and catching up. Achieving enough scale to be profitable on this model therefore requires equity backers with deep pockets, lots of commitment and no pressure for immediate returns.

Georg Hauer, N26’s general manager for the German-speaking countries

“The reason we’re not profitable yet is that we are reinvesting all our cash flows into product development, expansion and marketing,” says Hauer. “If we wanted to turn profitable earlier, we could quite easily tone down marketing costs, tone down product innovation, tone down our expansion. However, our plan is not to stay at five million customers and to become a mid-sized European bank.”

N26 is “definitely not” at the point where its investors are pushing the firm to switch its focus to profitability.

“Our investors are on board because they believe in our long-term vision,” says Hauer.

N26, like Revolut, already has customers across Europe. The second biggest market for both is France, where they each have more than a million clients. Yet N26’s decision to exit the UK earlier this year shows international growth is not easy when home-grown neobanks are already relatively well established, especially when there are cultural differences to navigate.

Very few firms have made the subscription model successful… It has not landed well in many cases – Mike Harding, Oliver Wyman

Global expansion on the basis of new technology requires enough capital to do it all at once, says Harding, as otherwise local competitors will have more time to exploit the opportunity.

“If you end up doing sequential international rollouts, you could end up being irrelevant in that market by the time you get there,” he says.

The hope for the bigger neobanks is that they have enough traction already to fare better than smaller rivals.

According to Boden, those founded in 2014 and 2015 – such as Starling, Revolut and Monzo – could now end up subsuming those founded a couple of years later. Indeed, that’s part of Starling’s expansion strategy in Europe.

“If you’ve only got tens of thousands of accounts or a couple of hundred thousand, it’s going to be very difficult to make your voice heard in this environment,” she says. “In the early stage of starting these banks, you do it by being on the circuit, doing the conferences, getting in touch with other startups, getting those startups to use your banking services. It’s a lot of face-to-face guerrilla marketing.”

Big challengers

Even the largest neobanks, of course, are still minnows in terms of their revenues and balance sheets. Increasingly, the established banks are taking the easy route to staying on top of digital innovation by partnering with or buying the upstarts that are supposed to be challenging them.

Monzo is rumoured to have rejected an approach by Royal Bank of Scotland three years ago, which triggered the launch of its in-house neobank, Bó. Now some are wondering if Monzo might reconsider, after RBS said in April it was closing Bó after only a few months.

Not that its chief executive thinks it will do such a thing.

“I didn’t do this to be bought by a big bank,” says Boden.

Things could get much worse for the neobanks, however, if lockdowns allow big traditional banks to dramatically reduce their reliance on physical distribution.

Jean Pierre Mustier, chief executive of UniCredit and head of the European Banking Federation, told Euromoney in late March: “The transformation we have achieved in the last three or four weeks has been much more intense and much more efficient than what we did in the past three years.”

He says this is because lockdowns have forced clients and staff to shift to digital channels.

However, from the neobanks’ perspective, this is their moment. They say that when people are shying away from physical money because of the risk of transmitting disease and are forced to do their banking online because of lockdowns, it plays into their advantages.

“This crisis will start the move from the old world to the new,” says Boden. “No one wants to handle cash in this environment.”

Entirely cloud-based IT systems, says Hauer, give the neobanks a huge advantage over the incumbents that is not going away.

“We could build an entirely new, state-of-the-art IT infrastructure, from scratch,” he says.

|

|

|

Mike Harding, |

Harding agrees, to an extent. He says neobanks have “showed what you could do with a modern tech stack” – it costs them about £20 a year to run a current account, compared with about £200 at traditional banks.

Many doubt the incumbents will ever manage to move on from legacy systems. Any move to the cloud would come with big risks and rewards for the banks that do it successfully, but so far none of the big firms have done it; so is it just science fiction?

“It’s more like returning to the moon,” says Paul Taylor, chief executive of core-banking fintech Thought Machine.

Boden speaks to her experience of drastically cutting costs at Allied Irish Banks as chief operating officer 10 years ago; something she says was only possible as the crisis in Irish banking was so deep.

“The big banks will never copy our cost base,” she says. The majority have data centres; the majority of them use VPNs [virtual private networks] that connect the organization; the majority have contact centres that need to operate on a physical site.

“If you compare us to the big banks, their distribution is too complex; they have too many branches. They have too many people, too many committees,” she adds. “They have tech that needs replacing. And they can’t afford to do so, not because they haven’t got the money but because changing those systems is very risky.”

Boden concludes that time will tell whether, now, banks are so squeezed they are forced into an even bigger restructuring than the ones that some managed after 2008.

Strict labour laws and public-sector bank ownership in continental Europe make it hard for traditional banks to embark on rapid reductions in the physical network, even as it becomes redundant.

According to Hauer, contactless and digital payments have taken off especially rapidly in Germany since the coronavirus, when cash was previously more important there than in many other countries. He says that could make it easier to attract the over-65s and late technology adopters.

“In the long-run, when people are more used to doing banking online and shopping online,” he says, “they will get more used to the idea of using an online-only account.”

He thinks the fact that N26 has a German banking licence will mean it benefits from any flight to quality that takes place as a result of the coronavirus.

On account

In the UK, incumbent banks suffered reputational damage by failing to distribute quickly enough government-backed loans to tide smaller businesses over during the lockdown. Under pressure, the government accredited fintech firms including Starling and OakNorth Bank to the scheme, giving them the chance to prove their mettle.

By late April, OakNorth had approved the majority of borrower requests for the guaranteed loans, about £40 million out of the £50 million allocated by the government.

|

|

|

Ben Barbanel, |

Head of debt finance Ben Barbanel says that its success is a reflection of its ability to harness and sort its information effectively, thanks to cloud technology – something the big banks cannot match.

OakNorth focused on lending earlier than other neobanks, he says, so most of the guaranteed loans it has distributed have gone to its existing borrowers.

Starling, on the other hand, has far more clients but at the smaller end of the market – so Boden expects the state-backed loans it distributes will mostly go to new customers.

“Most banks are telling customers: ‘Don’t call our contact centres as they’re too busy’,” says Boden. For the neobanks, working from home has been almost as simple as packing up their laptops, she says: “This is the environment we were built for.”

However, lending remains the key challenge for most neobanks, as it requires the kind of balance sheet and expertise that many of them lack.

Even a figure such as Ralph Hamers, chief executive of ING, believes that distributing in-house loan products will remain core to profitability as old retail banks transition towards app-based banking platforms.

Building up loan books is essential for neobanks, agrees Christopher Schmitz, fintech leader for Europe at EY, but it is hard to do when people are more cautious about taking on debt.

|

|

|

Christopher |

“Private equity and venture capital funds are taking a closer look at valuations, as they’re expecting a crisis,” says Schmitz. “If you’ve lived on account fees, probably you will need to show you can build a balance sheet and a credit book to increase your revenues streams.”

Part of the problem is that clients tend to use the neobanks – especially firms such as Revolut and Monzo – as a secondary or even tertiary account, to keep a better tab on spending or to avoid currency fees. It has been much harder to persuade clients to keep more money on account, which could then be used to create funding for high-margin SME and unsecured consumer lending.

According to Zachariadis at Manchester University, it’s no coincidence that OakNorth is both a rare example of a neobank that is profitable and one that has been successful by targeting loans from the outset – albeit a relatively small number of medium-sized borrowers.

“We’ve come at this the other way,” says Barbanel. “Taking a payment current account and morphing that into a lending business is a big step.”

Starling, although much more focused on smaller SMEs and retail than OakNorth, has an older and wealthier client base than most other neobanks, according to Boden.

She is also determined to use some of the bank’s burgeoning deposit base, at around £2 billion, for lending. Indeed, it’s partly for this reason that she is confident that Starling will become profitable earlier than the other neobanks, sometime in 2021.

“We match all the features from a big bank and then go 10 times better, with new features,” says Boden. “We don’t go wide and thin.”

But Starling’s loan book is still only about €100 million. In the long term, interest income is unlikely to make up more than about a third of its revenues alongside interchange fees and banking as a service.

“I think we will always be capital light,” she says. “We will always have low loan-to-deposit ratios.”

Subscription models

Meanwhile, Revolut doesn’t even have a loan book. That’s because of lack of demand from in its target client base of freelance web developers and the like, according to Adomauskas.

He adds that Revolut’s future beyond payments is as an Amazon Prime-style subscription model.

“The future bank can be built on a different business model,” he says.

Revolut therefore hopes to leverage its technological prowess to allow business clients to integrate proprietary payroll and invoicing software into their accounts, as well as third-party products for accounting, employee perks and pensions.

Its app also allows retail clients to trade stocks and cryptocurrencies, for example.

|

|

|

Vaidas Adomauskas, |

“We are building powerful tools to manage your finances,” says Adomauskas. “Banking should be subscription based.”

N26, similarly, does not intend to make credit a big part of its business. According to Hauer, that’s because, unlike payments and money management tools, regulatory issues make it harder to gain international economies of scale in lending.

As at Revolut, after interchange fees, subscriptions for N26’s premium accounts – offering services such as insurance and free international cash withdrawals for retail clients – are its next biggest revenue earner. Lending is not going to come close for the foreseeable future.

N26 only aspires to be the client’s main transaction account. It says it doesn’t mind if the salary is paid to a different bank then transferred in.

“Our business model is not interest-driven,” says Hauer. “Balance sheet, as a metric, comes from a time when interest rates were high and banks made money from their balance sheets. Nowadays banks try to reduce their balance sheets.”

Hauer’s view holds especially true in the eurozone, where interest rates are negative and have little chance of rising above zero. German banks, in particular, have recently pretty much encouraged clients to run down their deposits.

But not everyone is convinced that the neobanks will gain such huge economies of scale that interchange fees – even if complemented by subscriptions – will make up for interest income.

Bigger banks have struggled to impose even small monthly account fees on European clients.

The neobanks’ argue they are offering much more in the package. However, says EY’s Schmitz, it will be harder to persuade clients to pay for nice-to-have premium subscriptions when they’re more worried about their finances due to the impact of the coronavirus.

Retail banks have tried to bolster their offerings with personal financial management tools before and found it is not decisive in attracting clients.

“Very few firms have made the subscription model successful,” says Harding. “It has not landed well in many cases.”