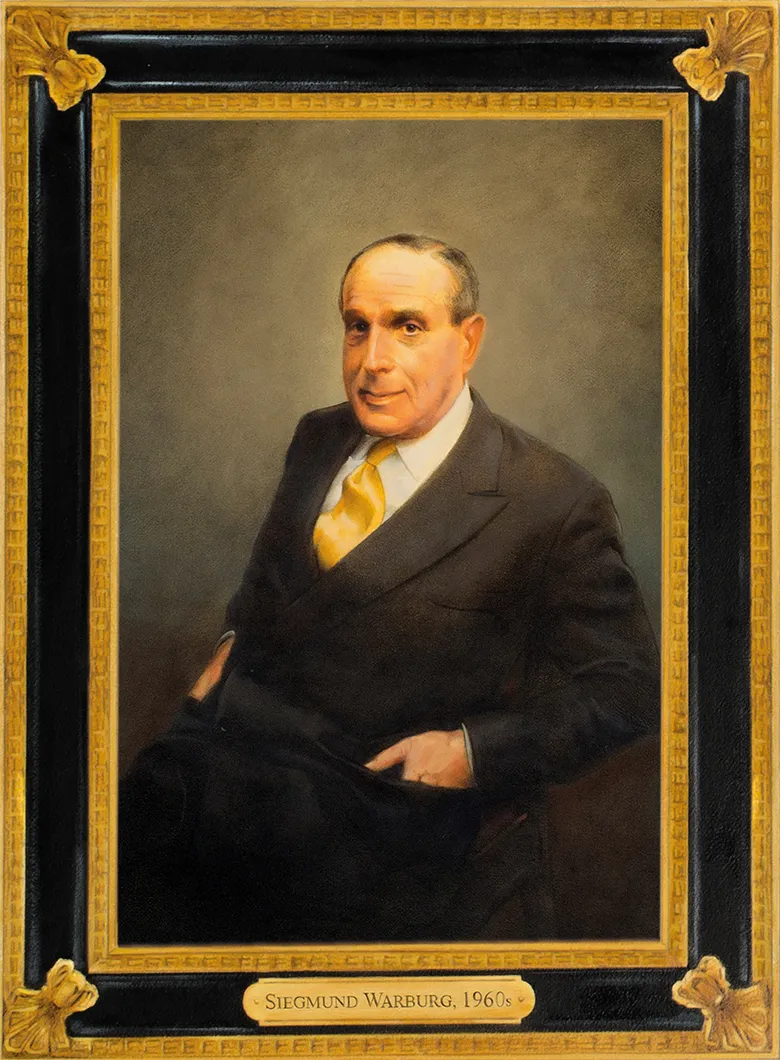

Illustration: Vince McIndoe

Sir Siegmund Warburg may not have liked this article. After all, although he was not half as hostile towards the media as is commonly believed, he did not care much for Euromoney. When he fell out with the magazine a little more than a year after its launch, the spat said rather more about Siegmund Warburg than it did about Euromoney itself.

|

THE BANKERS |

|

|

|

Print deadlines were such that preparations for the October edition, which was due to be distributed at the meeting in Copenhagen on September 21, began several weeks in advance. This meant ensuring that one of the showpiece articles, authored by Siegmund Warburg on the Eurobond market, was written by late August.

The galleys were collected by Euromoney on September 2, after a couple of tiny amendments had been agreed by Euromoney’s founder, Sir Patrick Sergeant and Warburg, together with the magazine’s first editor, Christopher Fildes. With characteristically minute attention to detail, these included the suggestion that: “The inverted commas should be dropped before and after the words “equity cult”.” The unwanted punctuation marks were duly removed and the magazine was shipped to Copenhagen on September 18.

Warburg appeared to be mildly amused by Euromoney’s excitement in advance of the World Bank meetings. The day after his meeting with Sergeant and Fildes, he sent a note to Sir Eric Roll, John Craven, Peter Spira and Tony Constance.

“[Patrick Sergeant] will attend this conference and apparently intends to take a large number of copies of that issue of ‘Euromoney’ with him which he anticipates distributing throughout the city of Copenhagen!” Warburg wrote.

Unknown to him as these copies made their way north, a cross-heading – “The case for regulation” – had been taken out of Warburg’s article because its position at the bottom of a column would have made the page look ugly. Worse still, a line of type which ought to have read “the flow of new issues to the market is regulated in one…” had also disappeared from the text. The line had featured in the proof inspected and approved by Warburg but had mysteriously been removed by the printers.

Warburg was furious. Sergeant was repentant.

“I can only say how sorry I am that it happened to you who have always done so much to help Euromoney,” he wrote. “I do feel very badly about this and I do hope you will forgive me.” It had, Sergeant added, been “an accident we all… deeply regret.”

|

|

Forgiveness was not, however, one of the many qualities for which Warburg would be remembered, even by his closest friends and colleagues. The apology elicited a remarkably frosty response which began “Dear Mr Sergeant”, even though the two men had known each other for 20 years.

“I have feelings of strong resentment against Euromoney… in view of the fact that the serious printing mistakes which were contained in the article were discovered in my office and that I had to draw the attention of Euromoney to these errors rather than the other way round,” Warburg wrote. “I think this is something that should not happen in any serious business organization.”

The punishment Warburg handed down to the magazine was severe. It was also symptomatic of his sometimes asphyxiating perfectionism and obstinate refusal to let bygones be bygones, which would have a corrosive influence on his relationships with some of his closest friends.

“I have discussed the matter with my colleagues here and we have come to the conclusion that in the circumstances it would be wrong for SG Warburg & Co to contribute any further articles to Euromoney,” was Warburg’s judgment.

A further apology from Sergeant and a personal promise to do his “very best to see that we improve ourselves,” appears to have fallen on deaf and unforgiving ears. Warburg was true to his word. Never again would he contribute to Euromoney; nor would he ever consent to being interviewed by the publication. He did, however, agree to speak to Investors Chronicle in April 1973 about the tie-up between Warburg and Paribas.

More memorably, he gave an extensive interview to competitor Institutional Investor early in 1980, which ran to 23 pages. In ‘Siegmund Warburg: A centenary appreciation’ published in 2002 to celebrate the centenary of his birth, the historian David Kynaston suggested that Warburg still had the 1970 contretemps with Euromoney in mind when he agreed to the lengthy interview with its principal competitor.

Whether or not this was true, there were other reasons why Warburg probably became more distrustful of Euromoney than he was of some other publications in the 1970s. One of these was that while he was an expert in using the media to advance the interests of his firm when it suited him to do so, he was famously uncomfortable with press stories about personalities.

Rightly or wrongly, there was a perception that Euromoney thrived on coverage of this kind, albeit probably long after Warburg’s death in 1982. For example in 2000, in his book ‘Falling eagle – The decline of Barclays Bank’, Martin Vander Weyer dismissively described Euromoney as: “The ‘Hello!’ magazine of the international capital market.”

Another reason why Euromoney may not have been Warburg’s cup of tea was that he heartily disliked league tables, which played an increasingly prominent role in the specialist press as competition in the capital market intensified. When he had broken with the “habits of a lifetime” to speak on the record to The Sunday Telegraph in January 1970, Warburg had been explicit about his disdain for these rankings.

“I see a certain danger for all merchant banking houses in being excessively keen on attaining or maintaining top positions in ‘league-tables,’” he told the Telegraph’s City editor, Patrick Hutber. “It is much more important in our kind of business to aim at quality of service irrespective of volume.”

Mass production, he added, was all very well among clearing banks but had no place in merchant banking. His industry, he said, should be regarded as analogous to the medical profession, where “individual service is paramount”.

Closely related to Warburg’s distaste for league tables was an equally haughty disrespect for advertising. At more or less the precise moment when the first edition of Euromoney was rolling off the press in the summer of 1969, Warburg and his colleagues were exchanging notes on how best to market the firm in Japan.

The brochures that US banks had used to promote themselves had had an “entertainment value” in Japan but had generated precious little business there, Warburg noted in June 1969.

“Altogether,” he added, “I still find it impossible – even after very great efforts at self-searching – to think of any instance where SGW & Co, or for that matter any other leading banking house, have obtained an important banking transaction as a result of advertising by press publicity or brochures.”

Workaholic

Had Euromoney written an article about Warburg in its inaugural edition in June 1969, it would have been a profile of an undisputed luminary within the City, who had presided over an organization whose share price had risen 20-fold in the previous decade.

It would also have been a profile of a renowned workaholic who at the age of 67 remained an indefatigable leader and a tireless networker. What is striking from a cursory glance through Warburg’s correspondence and diaries from June 1969 is the scope of his geographical interest and the breadth of his contacts.

A bout of bronchitis that month led him to cancel flights to Amsterdam, Frankfurt and New York (on a VC-10, his diary noted), as well as meetings with European companies such as BASF and Hoogovens. But it did not compel him to postpone his attendance at an Israel conference, nor his lunch with individuals ranging from Kiichirou Kitaura, president of Nomura, to the long-term head of Bear Stearns, Salim “Cy” Lewis, and Minos Zombanakis, then at Manufacturers Hanover.

Warburg’s correspondence that month, meanwhile, included a letter to Al Gordon of Kidder Peabody, expressing his delight at their cooperation in a Eurodollar issue for Sumitomo Metal Industries.

There was a note to Alexandre Lamfalussy, who was then at Banque Bruxelles Lambert, bemoaning the violent intensity of the competitive environment in the European capital market. Another letter from June 1969 is to George Bolton, formerly of the Bank of England but by now chairman of the Bank of London and South America, advising that SG Warburg’s expansion in Frankfurt was making “considerable progress”.

There was also the inevitable clutch of letters to the Zurich address of Warburg’s “beloved” Theodora Dreifuss, the trusted graphologist, psychoanalyst and confidante upon who’s say-so job applications often stood or fell.

Just think of the difficulties of a German Jew establishing himself in the post-World War II atmosphere in that then very closed community of London investment bankers, and emerging in due course as the acknowledged leader of them all – John Weinberg, ex-Goldman Sachs

Subjects covered in other letters dispatched that month included proposed financings for the UK’s General Post Office and the Channel Tunnel; concerns about suitable lead management candidates for a Chrysler Deutschemark bond; ideas about how best to promote the SG Warburg name in Japan; a discussion about the firm’s plans for domestic underwriting in the US; and the suggestion that a “combination between Daimler-Benz and Volkswagen” would make “a great deal of sense”.

Warburg’s correspondence about consolidation in the German banking industry in June 1969 also shone a light on his impatience with sloppy professional standards, which he was not shy of criticizing. In a letter to Hans Wuttke of Brinckmann, Wirtz & Co, Warburg said that he was not surprised that Daimler-Benz’s finance director, Joachim Zahn, had failed to get in touch as promised.

“Due to his excessive talking, he is as a rule late for all his appointments… by at least one month,” was Warburg’s caustic commentary on Zahn’s punctuality.

Not that his correspondence that month was all about hard-nosed commerce. Although Warburg complained about being “absolutely swamped with philanthropic demands”, his outgoing correspondence included a cheque for £50 to a memorial fund for the anti-apartheid campaigner Joost de Blank, the former archbishop of Cape Town.

Warburg’s workload was giddying in its international scope and it bore witness to the extraordinarily deep and varied global network he had cultivated over 35 years. Above all, it was a testimony to the respect he had garnered in building a business more or less from scratch in the potentially hostile and unwelcoming old boys’ club that the City of London remained until well into the 1970s.

It was this success, boosted by the sheer magnetism of Warburg’s personality, that was recognized in many of the tributes that arrived at 30 Gresham Street following his death in 1982.

“I’ve always felt that his business success was one of the most remarkable stories in history,” was the somewhat hyperbolic eulogy sent to Roll and Scholey by John Weinberg, who ran Goldman Sachs from 1976 to 1990 but had known Warburg since the 1940s. “Just think of the difficulties of a German Jew establishing himself in the post-World War II atmosphere in that then very closed community of London investment bankers, and emerging in due course as the acknowledged leader of them all!”

Watershed

It would be difficult to underestimate what Warburg achieved after escaping Nazi Germany in 1933, settling in London and establishing the New Trading Company. It is, however, hard to get away from the reality that by 1969, many of Warburg’s greatest triumphs may already have been behind him.

One of the most notable of these came in 1958, when SG Warburg shook up the City’s somnolent and clubby network by advising Reynolds Metals and Tube Investments on the acquisition of British Aluminium in the UK’s first hostile takeover. The deal led some to denounce Warburg as a parvenu (or worse).

Peter Spira was at SG Warburg from 1957 to 1974, latterly as vice-chairman. In his autobiography, ‘Ladders and snakes’, published in 1997, he noted that the firm’s role in the contested bid was a “watershed” and a “tremendous stepping-stone in putting Warburgs on the map.”

More or less overnight, SG Warburg had become the go-to bank for the board of any UK company contemplating a hostile takeover.

But it was Warburg’s role as the founder of the Eurobond market in 1963 that probably did more than anything else to establish his position as a pioneer in the international capital markets.

There is some difference of opinion as to how closely he was involved in the nuts and bolts of the Autostrade transaction, which raised the curtain on the Eurobond market in 1963. But his biographers and countless journalists since then have been in no doubt about the driving force behind the new market.

“If anyone could claim to be the father of the Eurobond market it was Siegmund Warburg,” wrote Niall Ferguson in his biography, ‘High financier – the lives and time of Siegmund Warburg’, published in 2010.

Tellingly, however, Ferguson argues that it would be wrong to assume that Warburg’s principal motivation for developing the Eurobond market was enhancing his firm’s profitability or even helping to strengthen London’s credentials as a financial centre.

“He always conceived of it as simply a first step towards linking together the European capital markets and thereby advancing the wider project of European integration,” was Ferguson’s interpretation.

Beyond his successes in the Euromarket and mergers and acquisitions, which boomed in the 1960s, Warburg’s greatest achievement during the decade was possibly the identification, recruitment and nurturing of a team of outstanding bankers who would spearhead the firm’s expansion.

Warburg always conceived of the Eurobond market as simply a first step towards linking together the European capital markets and thereby advancing the wider project of European integration – Niall Ferguson, biographer

Many of these were young men, in whose career development Warburg took a personal interest.

(As was usual in the City of London in the post-war period, very few of the recruits were women. One former colleague recalls: “Siegmund was very interested in all aspects of women including their business acumen. He took great care to get to know colleagues’ wives, acquiring knowledge of and exercising influence over their husbands through them. He frequently observed that in some cases they would have made better bankers than their spouses. I do not believe he would have had any constitutional objections to the explosion of women in the financial field – in all likelihood quite the opposite.”)

“It was the greatest collection of talent under one roof in the City’s history,” says Mark Lewisohn, now a group managing director at UBS. He is the grandson of Henry Grunfeld and his father, Oscar, worked at SG Warburg from 1962 to 1995.

Lewisohn is now the only member of the Warburg/Grunfeld dynasty still at UBS. Having joined the firm in 1989, he is also a rare embodiment today of the loyalty and long-termism espoused by the SG Warburg founders.

By the early 1970s, however, the team that Warburg had built and the talent he had nurtured was already starting to disintegrate, in part due to his own increasing irascibility.

The bond market veteran, Gert Whitman, accredited by many for doing much of the hard work on the Autostrade transaction, had left in 1969, barely on speaking terms with Warburg. By then, so had another of the architects of the inaugural Eurobond, Ian Fraser, who had been invited by the Bank of England to head its Panel on Takeovers and Mergers. Spira decamped to Sotheby’s in 1974, and John Craven moved to Credit Suisse White Weld the following year.

At the same time, competitive pressures were intensifying in the Euromarket. The rules of engagement had started to change, playing into the hands of the large trading houses, such as Credit Suisse White Weld, where the young Oswald Grübel had begun his career.

“By the early 1970s, it was becoming clear that the trading houses were starting to dominate the market,” recalls Grübel, who went on to head Credit Suisse and UBS. “Warburg were minor traders.”

Nevertheless, against lengthening odds and the backdrop of a worsening economic environment, SG Warburg consolidated and even strengthened its position among its British competitors in the Eurobond market. As Kynaston pointed out in his ‘Centenary appreciation’, in 1976 the firm managed or co-managed more Eurobond offerings (52 in total) than all the other British merchant banks put together.

Undiminished

To his enormous disappointment, the success Warburg enjoyed in the London market was seldom replicated elsewhere.

It may be going too far to say, as Ferguson does, that the last chapter in Warburg’s life as a banker was, “in the end, a story of failure”. But it is generally agreed that Warburg’s energetic attempt to penetrate the US market misfired due in large part to his misreading of the competitive environment and over-inflation of his own pedigree and influence.

As Ron Chernow puts it in his 1994 book ‘The Warburgs’: “New York was a formidable place to penetrate, and Siegmund overestimated the mystique of the Warburg name.”

|

Warburg had high hopes that the creation of a joint venture with Paribas in the US in 1973 and the acquisition the following year of the Chicago-based securities firm, AG Becker, would be the key to unlocking the US market. But the Warburg-Paribas-Becker group was never able to build an efficient distribution network in the US.

Yet by the end of the 1970s Sir Siegmund’s mystique was undiminished, his influence unquestioned and his reputation untarnished, perhaps even strengthened. Striking evidence of this came early in 1980, following the publication of the lengthy interview that Warburg gave to Cary Reich of Institutional Investor. The immediate response to the interview was a mail-bag overflowing with letters from acquaintances, competitors and strangers congratulating Warburg and thanking him for sharing his insights with the general public.

One of these was sent by Bill Mackworth-Young, chief executive of Morgan Grenfell since 1973.

“I cannot possibly let this pass without thanking you for your generous comment about Morgan Grenfell and, less importantly, myself,” wrote Mackworth-Young after reading the interview.

“Such generosity towards one’s competitors used to be a commonplace among the leading houses of the City. Sadly it is now not so common, and we are all grateful to you for maintaining so excellent a tradition.”

Mackworth-Young signed off by adding that: “I think you also know that the respect between our two Houses is entirely mutual.”

It would be easy to dismiss this sort of thing as exaggerated diplomatic protocol. But this was the same Morgan Grenfell (albeit under different leadership) that had reportedly accused SG Warburg of “monstrous and unforgivable” conduct during the contested British Aluminium takeover in 1958.

The strength of feeling caused by Warburg’s role in the so-called Aluminium War had allegedly prompted Morgan Grenfell to refuse to do any business with SG Warburg for the following 15 years.

Of the 48 letters arriving in the Gresham Street post-room after the Institutional Investor interview, Warburg may have drawn the greatest pleasure from the one he received from Bob Baldwin, president of Morgan Stanley.

Baldwin, who transformed Morgan Stanley as head of the bank between 1972 and 1983, wrote to congratulate Warburg on “the marvellous portrait that was painted of [him] and [his] accomplishments over the years in the international financial field.”

This is likely to have resonated with Warburg, who was a great admirer of Morgan Stanley in general and of Baldwin in particular. Some months before his interview with Reich, Sir Siegmund had lunched in New York with Baldwin and 16 of his junior managing directors, and had come away highly impressed with the younger generation.

“I found most of them intelligent and lively and impressively well informed, with charming manners,” Warburg reported back to Gresham Street. “The chief questions addressed to me concerned the Eurodollar market and in particular how SGW & Co was the only one among the European private banking houses which had been able to maintain a strong position in that market in spite of the almost overpowering financial and organizational strength of the universal banks.”

Warburg’s note ended with some reflections on the relationship between Morgan Stanley and SG Warburg, to which Baldwin reportedly attached “great importance”.

“There is no doubt that amongst our various competitors throughout the world, Deutsche Bank on the one hand and Morgan Stanley on the other are those with whom we should try to develop further as far as we possibly can a special relationship,” Warburg wrote.

In both houses, he noted, there were individuals who were “inclined to arrogance”; but he added that at least representatives of Deutsche and Morgan Stanley had something to be arrogant about.

Warburg had no way of knowing then that the special relationship between his firm and Morgan Stanley would nearly blossom into a marriage 12 years after his death. Dubbed the investment bank of the future by some commentators, this union would have created one of the world’s largest investment banks with over $11.5 billion in capital.

The courtship developed against the backdrop of a catastrophic year in 1994. Warburg’s revenues had collapsed and morale had been punctured in the slipstream of the surprise hike in US rates at the start of the year.

In his 2003 analysis, ‘Morgan Stanley and SG Warburg: Investment bank of the future’, professor James Sebenius of Harvard Business School noted: “The near absence of investment banking earnings was a severe setback to Warburg at a time when the firm was spending prodigiously to expand its New York operation and its bond division.”

The result, added Sebenius, was that: “When John Mack travelled to London for a luncheon meeting with [Warburg chief executive] Lord Cairns in September 1994, it was as if the US cavalry had arrived to rescue Warburg from dire straits.”

That cavalry stopped in its tracks three months later when Morgan Stanley abruptly pulled the plug on the proposed merger, reportedly codenamed Project Sparkling.

Sir Siegmund himself would have been deeply saddened by the shambolic failure of the talks with Morgan Stanley. He would also have been disconsolate at the circumstances leading up to the eventual loss of SG Warburg’s independence, catalyzed as it was by precisely the sort of hell-for-leather expansion he had always cautioned against.

“Bigness as such has never been and should never be our ambition,” Warburg had advised his colleagues in a lengthy and heartfelt note in 1964 outlining his blueprint for ensuring that the firm’s rapid expansion in the early 1960s was sustainable.

The eventual sale of SG Warburg to Swiss Bank Corp (SBC) in May 1995 came after several months of turbulence marked by a series of profit warnings and the failed merger attempt with Morgan Stanley. The price at which SBC had been able to acquire the enfeebled UK merchant bank would have been another source of sorrow for Warburg, as it was for his former colleagues.

Deficiencies

Marcel Ospel, chief executive of SBC, readily conceded that he had picked up Warburgs for a song.

“It was certainly inexpensive,” he told Garry Evans, editor of Euromoney, in April 1997. “If you compare it to premiums that prevail in North America, it was very cheap.”

In a sad epitaph for the house that Sir Siegmund had built from scratch, Ospel implied that Warburgs had become cheap for a reason. By the time SBC had swooped, he said, “deficiencies in English merchant banking were becoming apparent.”

Warburgs, he added, “wasn’t managed the way an ambitious investment bank should be these days.”

SG Warburg itself would put a brave face on the breakdown of the merger talks. In an internal note circulated following the announcement of the firm’s sale to SBC, Henry Grunfeld described the abandonment of the tie-up as a blessing in disguise.

“Although we and the Americans ostensibly speak the same language, the American mentality is totally different from ours and there would have been serious ‘culture’ clashes which would have affected us as the lesser partner very badly,” he wrote in an internal memo in May 1995.

The public message was that Grunfeld warmly endorsed the acquisition by SBC, which he said he was “not at all unhappy about.” He could not, however, resist taking a swipe at Barings, the bankruptcy of which in 1995 had “at one blow diminished the confidence which the merchant banks in London had so painstakingly won over 200 years.”

It was defiant stuff. But it was a very different story to the one Grunfeld had recounted in a letter he had sent to Warburg’s former personal assistant, Doris Wasserman, six months earlier, in which he confided that the press reports had not told the “real story”.

He added that: “In our opinion and in the opinion of the top people at Morgan Stanley, it would have been a marvellous fit… During the negotiations I quoted Siegmund Warburg when many years ago he said our ambition was to be the Morgan Stanley of Europe.”

It is doubtful that Grunfeld’s public contentment at the incorporation of Warburgs into SBC was shared in private by many of his former colleagues.

“I really used to shudder when I read on SGW’s writing paper in tiny print: ‘a subsidiary of Swiss Bank Corporation’, before that bank was absorbed by UBS,” is Spira’s recollection today.

Re-branding

The purchase of SG Warburg by SBC and the merry-go-round of ownership changes and re-brandings that followed it marked the beginning of the end for a firm that had been proudly independent under Siegmund’s name since 1946. Enervated and increasingly fragile, the Warburg name lived on for eight years after SBC’s acquisition. But it eventually passed into history on June 9, 2003, when UBS officially dropped the Warburg and PaineWebber brands from its brokerage and investment banking divisions.

Lewisohn says that to his great credit, Ospel, who oversaw the re-branding, was courteous enough to inform him that the Warburg name was to be axed well in advance of the official announcement. It was inevitable that Lewisohn was saddened by the news, but he says that with the benefit of hindsight it was a mercy that there was no association between the Warburg name and the events of 2008.

It’s easy to see why. Sir Siegmund was uncomfortable enough with the firm he had originally set up in 1934 bearing his name at all. He would have been dismayed at the thought of a bank with the name of Warburg being forced to write down $44 billion of toxic assets in 2008.

The aftermath of the sub-prime fiasco was by no means the only development of the new century at UBS that would have appalled Warburg. He would have been aghast at the Libor scandal and by the jailing of a UBS trader for fraud in 2012. He would also surely have been horrified by the brutality of the cutbacks in October 2012 that claimed 10,000 jobs at UBS.

Many of the individuals who were casualties of the cull in London, including some senior bankers, were reported to have arrived at UBS headquarters that morning to find their security passes no longer functioned. That was hardly in keeping with the haute banque standards of fair play and integrity Sir Siegmund had worked so hard to imbue among his colleagues.

|

|

|

William Gruver, Bucknell University and ex-Goldman Sachs |

Sir Siegmund would also have been dismayed by the political events of recent years. As early as 1956, SG Warburg had been one of 50 signatories to a ‘Statement on a European Common Market’ calling for the “direct co-operation and participation” that would allow Europe to compete with the US.

Although he would periodically veer towards euroscepticism, it is hard to imagine him being anything other than distraught at the UK’s exit from the European Union, as well as at the broader re-emergence of isolationist politics on both sides of the Atlantic. As Sir David Scholey, former chairman of SG Warburg, tells Euromoney: “Siegmund would have found this a very difficult world to live in.”

How much of a mark he left on this difficult world is open to debate. His legacy will live on in a purely bibliographical sense at the library of the London School of Economics. Thanks to note-taking and filing procedures at SG Warburg bordering on the obsessive, there are 274 boxes of original documents chronicling Sir Siegmund’s life and business career in the library, more than 150 of which are filled with his letters.

Whether the values Warburg championed can survive either in the City or the broader global financial services industry is another question altogether. Lewisohn concedes that many of those values are under threat – none more so than the long-termism that was a cornerstone of the SG Warburg philosophy.

Warburg’s own commitment to constructing long-term business relationships was not empty patter of the kind liberally used by banks today. One of Sir Siegmund’s guiding principles, wrote Roll in his 1985 memoir, ‘Crowded hours’, was that “the modern craze for better results each year was misguided and dangerous”.

The rejection of a spurious natural law dictating that “every year had to be better than the previous one” would be regarded as heresy today.

“The pressure on the investment banking industry to generate the revenues it needs to justify the bonuses it pays are intense,” says Lewisohn.

The demands of quarterly reporting mean that those revenues need to be generated within sometimes impossibly tight deadlines.

Sir Siegmund valued relationships for the long term, and although he didn’t claim to wear a clerical collar, he was driven not by a desire to make money but to create value for his clients – William Gruver, Bucknell University

Short-term pressures to generate earnings, along with the technology that has revolutionized banking and more cosmetic changes, such as open-plan offices, are all elements that would have bewildered Warburg and Lewisohn’s grandfather, Henry Grunfeld.

“But what hasn’t changed is the personal side of the business,” says Lewisohn. “The model of the relationship banker pioneered by SG Warburg is the model we continue to espouse today. That is a link to the past which I believe will remain relevant for a long time.”

William Gruver shares Lewisohn’s optimism. Today, Gruver is a professor at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania, where he teaches investment banking, among other financial disciplines. In 1980, as a junior employee at Goldman Sachs, Gruver had what he describes as the “temerity” to write to Warburg after the publication of his interview with Institutional Investor.

“What appealed to me about Cary Reich’s piece was that it showed that Sir Siegmund was something of an outsider who refused to do things the traditional way,” Gruver recalls. “He valued relationships for the long term, and although he didn’t claim to wear a clerical collar, he was driven not by a desire to make money but to create value for his clients.”

Will Gruver’s students carry any or all of that ethos into the next generation?

“Those values live on today, but the Warburg legacy is probably on life support,” says Gruver, who was at Goldman Sachs until 1992, latterly as chief administrative officer of the bank’s equities division. “You see those values in some of the newer boutique firms that have broken away from the bulge bracket on either side of the Atlantic, which are already gaining market share in areas like M&A.

“This gives me hope that the banking industry will come full circle in the next 30 years, in the sense that it will come to recognize that there is more to a business relationship than the next transaction,” adds Gruver. “Then again, I’m an undying optimist.”

Be sure to read the June 2069 edition of Euromoney to discover how warranted that optimism turns out to be.