For over four decades, China has served as the world’s factory. Since 2008, a strategic shift dubbed by officials as “vacating the cage to change birds” has seen the country deliberately pivot to higher-value industries, anticipating that certain lower-value production would move elsewhere.

Post-Covid, supply chains appear to be shifting away from China as corporates react to escalating geopolitical tensions, Covid-19 disruptions, and changes in China’s domestic policies.

The latter was most acutely felt in the summer of 2021 when the sudden ban on commercial providers of after-school tuition hit many global investors. This coincided with an investigation into the ride-hailing app Didi Chuxing that eventually led to a freeze on US IPOs for Chinese companies.

Covid-19 lockdown measures compounded the sustained crackdown on property developers and internet platforms that had already begun.

The change has certainly been dramatic. In 2021, China hit a record $130 billion in private equity investments, but by 2022 deal flow had slumped to $64 billion, a seven-year low. It has slumped further, to $21.5 billion in the first half of 2023, the lowest six-month total in nearly 10 years, according to AVCJ Research.

There has also been a 10% decline in total foreign direct investment in China in the first seven months of this year, according to Fitch Ratings.

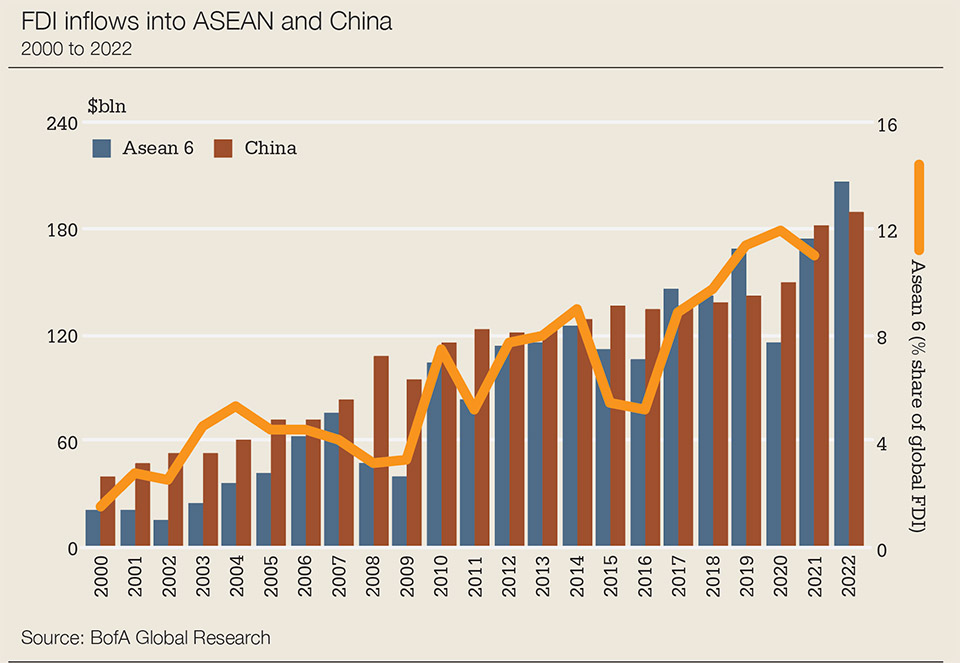

That has been matched by a shift of capital to China’s neighbours. The Asean bloc attracted over $200 billion in FDI in 2022 – a sharp increase from the early 2010s, when the annual average was around $100 billion, according to BofA Global Research.

Since 2017, Asean has surpassed China in attracting FDI in four out of six years, reversing the trend from 2000 to 2015.

But where capital goes, supply chains do not necessarily follow. For example, Singapore, one of the biggest beneficiaries of regional capital inflows from China, has seen 68% of new capital flowing into the financial sector, but only 7% to manufacturing.

Wide media coverage of multinational corporations such as Apple shifting manufacturing from China to India are also fuelling the perception that supply chains are shifting. But in fact, Apple had 276 supplier locations in mainland China in 2022, up from 262 in 2021, accounting for 39% of its global total, according to a UBS report. Meanwhile, the number of Apple’s supplier locations in India increased from 11 to 13 during the same period, representing less than 2% of Apple’s overall total.

Rhetoric

The future of China is at the heart of any bank’s Asia strategy. Recent conversations with bankers in the region – from US, European and Asian firms – offer a shared view: The relocation of manufacturing capacity out of China is more rhetoric than reality.

“No one is withdrawing from the country,” says one corporate banker from an international firm. “They don’t want to miss out on a rebound in China, which could happen at any moment. Additionally, they don’t want to risk upsetting regulators.”

The result is a shift in the headlines, from ‘decoupling’ to ‘China Plus One’ – a strategy that sees many firms keep their production in China while picking another manufacturing base as a hedge. There is also some fear that widespread decoupling from China would greatly increase production costs, seriously hampering global efforts to tackle inflation.

Rather than moving away from China, regional supply chains appear to be being integrated into other Asian economies, without necessarily impacting activity in the former country

Meanwhile, no single economy has the potential to match the scale and competitiveness of China’s onshore supply-chain network. Vietnam and India may be the two most promising competitors, but they both have drawbacks.

Vietnam has relatively small-scale infrastructure, and with some important gaps, as a recent UBS report notes, while India suffers from high logistics costs, low labour productivity and regulatory impediments that are perennial challenges.

Indeed, despite wage rates nearly three times higher than these alternatives, China’s absolute cost for manufacturing – including labour, freight, power and costs of goods supplied – is only 5% higher than India, the lowest-cost location in the region.

Integration

Rather than moving away from China, regional supply chains appear to be being integrated into other Asian economies, without necessarily impacting activity in the former country.

In 2020, Chinese economist Zhan Shi published a book exploring the impact of the US-China trade war and the US-imposed tariffs on China’s supply chain. He concluded that instead of transferring an entire supply chain to Vietnam, only a few links – perhaps processes such as assembly – were transferred. Shi termed this phenomenon ‘spill over’.

By moving the final stages of production to other countries, businesses can circumvent tariffs by labelling good as having been made outside China.

The more such transfers occur, the more deeply embedded the supply chain becomes between China and southeast Asia.

Data supports this view. While China’s exports to the US have dropped, its exports to southeast Asia have grown considerably, and the continued rise in its exports of intermediate goods has become increasingly important for other Asian countries.

For banks, helping Chinese firms expand these corridors is an opportunity – particularly for the China-India and China-Europe corridors in sectors such as electric vehicles and clean energy.

China already manufacturers three out of four EVs sold in southeast Asia and holds an 8% market share in Europe – a figure that is likely to rise, short of new regulation.

The key competitiveness of Chinese manufacturers lies in their robust and flexible domestic supply chains, which helps to keep costs low and enable rapid product iteration. Rather than shifting the primary manufacturing location, these firms want to expand sales in other territories and leverage the expertise they find there, such as European design capabilities.