|

The Brazilian government is resisting pressure to reconsider its proposal to change how BNDES, the state development bank, charges interest rates to lenders.

The government has written a bill that will phase out the current long-term TJLP rate – which is set by committee and is currently 7%, below the country’s Selic base rate of 10.25% – and replace it with a new TLP rate, which will be linked to the yield on inflation-indexed government debt.

However, in a recent interview with local financial newspaper Valor, Paulo Rabello de Castro, the new chief executive officer of BNDES, suggested the TLP rate could instead be linked to the consumer price index.

Two senior BNDES vice-presidents resigned after Rabello’s comments about possible changes to the new TLP rate were reported, showing the sensitivity in Brazil about the new financing rate. There has also been an uptick in local criticism about the changes, with trade associations beginning to lobby against the changes.

|

|

|

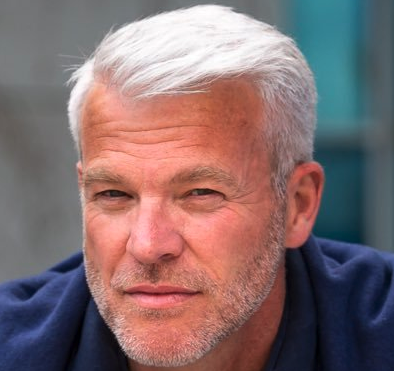

José Velloso, Abimaq |

For example, José Velloso, chief executive of the Brazilian Machinery Builders’ Association (Abimaq), said the changes to TJLP would increase the cost of long-term funding.

According to local media reports, he said: “The new TLP will make the cost much greater than in other countries, taking the competitiveness of the industry, of buyers of capital goods.”

However, finance minister Henrique Meirelles and planning minister Dyogo Oliveira were both quoted by Reuters this week as dismissing any changes to the calculation of the new BNDES lending rate.

This steadfastness is due to the fact that this change is a key part of the government’s reform programme for the financial sector – and is backed by Ilan Goldfajn, the central bank’s president.

A report from the World Bank earlier this year, titled Brazil Financial Intermediation Costs and Credit Allocation, highlights the negative impact on fiscal and monetary policy of the current TJLP rates.

According to the report, the TJLP rate in Brazil is responsible for 72% of all “earmarked” lending. Earmarked lending is credit extended by the government at subsidized, below-market rates.

At the end of 2015, half of total credit in Brazil was earmarked, which was back to the levels seen in the late 1990s after it had fallen to one-third of total credit in 2007, just before the financial crisis hit.

|

|

Antonio Nucifora, World Bank |

Antonio Nucifora, lead country economist for Brazil at the World Bank, has been discussing the issue with the government and the central bank as they move to reduce the amount of subsidized directed credit through the public banks.

In an emailed response to Euromoney questions, Nucifora says: “A key piece of this is the medida provisoria [executive order] approved by government in April to move from the TJLP to a new system called TLP, that is linked to long-term market rates to finance BNDES – which would de facto limit the amount of subsidies in BNDES lending.

“This medida provisoria will need to be discussed and approved in the congress within four months for it to remain effective. Hence it will be discussed in congress in July.”

The main findings of the World Bank’s report are stark in supporting the government’s aims to reduce earmarked credit.

The report highlights the adverse effects that TJLP has on the Brazilian economy. First, the fact that banks make small profits on the earmarked credit sector means that they “seem to compensate with higher rates on non-earmarked credits and fee income”.

This increases the costs of interest rates to the freely allocated market sector and damages investment in the economy from those who cannot access earmarked credit.

Statistical proof

Perhaps surprisingly, the report shows that those companies that can access earmarked credit are those that are in less need and had access to alternative forms of long-term funding – including the international debt markets.

The report states: “In the recent period, firms that had higher probability of accessing earmarked loans were older, larger … mixed capital companies such as Petrobras, Eletrobras and Furnas were the main beneficiaries.”

The report even uncovers statistical proof that the provision of subsidized credit led these firms to “lower their financial expense and increase their leverage”, while “firms that received earmarked credits did not invest more”. The report adds that “earmarked loans may have been used for financial arbitrage”.

The fiscal costs of having half of credit extended at subsidized rates are enormous, and the World Bank estimates the annual costs at around 1.5% of GDP in 2015. The majority of these costs are from the financing provided to BNDES, which is provided by the government issuing debt at market rates (14% on average) while BNDES lends at an average of 7%.

The report says that the increase in the interest-rate differential – in recent years before the Selic began to fall again in 2016 – and the growth of earmarked credit meant that government costs increased as a general share of government revenues from 1% in 2009 to 2.6% in 2015.

There are also negative impacts to monetary policy. As half of credit isn’t linked to Selic, “changes to the policy rate have to be larger to have the same impact”, according to the report.

Also, as earmarked credit is unevenly distributed among sectors – it is skewed towards manufacturing and services sectors, which receive the largest shares of total earmarked credit, at 31% and 27% respectively, followed by energy at 16% – monetary policy has a distortive impact on credit cost and allocation.