In early February 2020, weeks before Covid-19 sent the world into lockdown, the Republic of Ghana stormed the debt capital markets with a $3 billion Eurobond. The deal marked the longest-ever bond from sub-Saharan Africa, with a 40-year maturity. At a time when developed market investors were in a desperate search for yield, it priced at just below 9%.

Jump to:

Although bankers lauded the deal at the time, Ghana was borrowing far too much. In February 2023, the country defaulted on its Eurobonds. Before a later restructuring of local-currency debt, almost half of its government revenue was going on interest payments, according to Fitch Ratings.

Ghana is far from alone.

Frontier-market sovereign debt levels mushroomed in the 2010s on the back of low interest rates in the developed markets. Meanwhile, as the population and infrastructure needs of developing countries have risen, Chinese policy lenders have, until recently, filled the gaps left by public-sector lenders from the West.

Indeed, Chinese development finance dwarfed that from Western states in the first two decades of the 21st century, particularly after the 2013 launch of the Belt & Road Initiative. In Africa alone, China signed loans totalling almost $160 billion by 2020, according to research at Boston University. But compared with the West, China has given far more of its development finance in loans than grants, and at rates of more than 4%, according to AidData. That compares with Western and multilateral lending rates of 2% or less.

Now these flows are drying up. Even before Covid hit, Chinese lending to Africa started to slow because of concerns about indebtedness. African countries have subsequently had to rely more on sources such as Afreximbank, which is growing rapidly but has a lower credit rating than Chinese bilateral lenders, making its loans potentially more expensive.

More recently, in the wake of higher US interest rates, frontier-market Eurobond issuance has also evaporated.

The global north can’t afford for so many countries to be unable to fund themselves officially or privately for such a long period

Jay Collins, Citi

In Ghana, the stalled construction of a $350 million national cathedral has become a symbol of how easy access to financial markets has facilitated state spending on projects of dubious value. Outsized hope for oil wealth after discoveries 15 years ago may have been partly to blame.

There are projects equivalent to Ghana’s cathedral across Africa and beyond – frequently built and financed by China. It is not just the ghost cities and empty stadia from the last oil boom in countries such as Angola; countries with little or no oil wealth are also now starting to rue the insufficient economic returns of the roads, railways and dams they paid for using Chinese debt and contractors.

After having ramped up debt in the last decade, many African and Latin American countries have seen an unrelenting series of crises: the collapse in economic growth due to Covid; higher costs for food and energy imports following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; and finally, much higher interest rates.

Sovereign defaults had already risen to a record five in 2020, when Zambia and Lebanon defaulted. After the 2022 defaults of Ukraine and Belarus, Sri Lanka was added to the list in May last year, triggering mass protests and the resignation of president Gotabaya Rajapaksa. That was before the impact of higher US interest rates kicked in. After Ghana’s default early this year, ratings agencies suggest countries such as Tunisia and Argentina could be next.

Path to normalcy

Since last May, sovereign debt spreads for the riskiest 10% of countries have been trading at a higher level than at any point this century, according to data from Bloomberg and Oxford Economics.

For some, this brings back memories of the 1980s and 1990s, when a prior retrenchment by international lenders saw poorer nations locked in a cycle of high debt, low growth and an inability to access new international borrowing – not least because banks were so slow to properly restructure the debt. Unlike the 1980s, this is not yet a systemic issue for the Western financial system.

But that could change, given the number and importance of sovereigns with yields to maturity of more than 8%, says Jay Collins, Citi’s vice-chairman of corporate and investment banking.

“The global north can’t afford for so many countries to be unable to fund themselves officially or privately for such a long period,” says Collins. “We should be reducing the number of countries on that list as fast as we can. We’re not creating movement on that path to normalcy as quickly as we should be.”

Worries about Kenya’s ability to meet a $2 billion Eurobond payment maturing next year have been particularly unsettling. Even more than Ghana, Kenya has been closely associated with the ‘Africa rising’ narrative that became widespread a decade ago – the idea that African economies are the successors to the Asian Tigers.

Kenya’s bonds rallied in July after the IMF upsized a post-Covid support programme launched in 2021. Kenya also tapped a $500 million syndicated loan arranged by international banks in the same month.

But Kenya’s balance of payments is still under pressure. Its central bank reserves have steadily fallen to around $7 billion due to high oil and food import costs made worse by a drought. Recently, the opposition has jumped on popular anger at government moves to cut subsidies and boost tax revenue, sparking violent protests.

Whenever there is a lot of clamour and controversy around sovereign debt relief from official creditors, if history is any guide, they then become very reluctant for new lending afterwards

Reza Baqir, Alvarez & Marsal

The Central Bank of Nigeria’s August publication of financial statements – for the first time in seven years, and revealing $7.5 billion of securities borrowing from JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs – has also brought new fears about Nigeria’s sovereign finances, after the inauguration of new president Bola Tinubu in May led to increased hopes for reform.

It is not just in sub-Saharan Africa where the risks lie. Egypt and Pakistan both face difficult-to-meet Eurobond maturities from next year. Their leaders face a balancing act between maintaining political stability and adhering to IMF-led reforms. If interest rates remain high for much longer, investors’ main hope is that the countries’ regional importance will win them support from the Gulf and China.

As in Africa, Covid hit Latin American economies especially hard. Brazil and Mexico have the advantage of deep local capital markets, but Bolivia’s foreign-exchange reserves have been in freefall and El Salvador’s enthusiasm for bitcoin left it heavily exposed to last year’s crypto crash. A political crisis in Ecuador this year has also seen its bonds move further into distressed territory.

Higher oil prices after 2020 have been a rare support for some countries in an otherwise unforgiving global context of rising inflation and low growth. They allowed Angola and Gabon to stave off default and supported Nigeria’s repayment capacity. In the 1980s, there was no such saviour from the commodities markets.

Nevertheless, because of higher interest rates, even relatively low-debt countries are struggling to roll over that debt, notes Reza Baqir, head of sovereign debt advisory at Alvarez & Marsal.

Just as troubling, there is risk of a longer-term fall-off in lending from the bond market and from public-sector sources in China and elsewhere.

Baqir, a former IMF restructuring expert and Pakistan central bank governor, cites IMF research showing that public-sector flows to developing economies decreased dramatically after the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative 20 years ago, something he puts down to the political difficulty of continuing to lend.

“Whenever there is a lot of clamour and controversy around sovereign debt relief from official creditors, if history is any guide, they then become very reluctant for new lending afterwards,” he says.

The money needs to continue to flow, Baqir adds, both for refinancing and because of rising capital demands related to energy transition and mitigation of the impact of climate change. A case in point is last year’s devastating flooding in Pakistan: reconstruction needs will top $16 billion, according to the World Bank.

The Common Framework

This need for new money from public and private lenders is why it is so important to have swift debt restructurings that seem equitable to those writing down the debt. So far, the signs are not encouraging. Since 2020, because of delays in restructuring negotiations, countries have languished in default for three times longer than the 20-year median, according to Fitch Ratings.

Zambia has been the test case for restructuring in a world in which China is by far the biggest bilateral lender. It has also been emblematic of the deep difficulties of including China in workouts.

China and other emerging-market bilateral creditors of new importance are not members of the Paris Club of mainly Western official creditors. Partly triggered by Covid-19, the G20 launched a new Common Framework in late 2020 to bring together the Paris Club with China, India and Saudi Arabia in the debt restructurings of low-income countries. Zambia, with Ethiopia and Chad, was one of the first to apply for debt relief under the CF in early 2021.

Frontier Eurobonds slow to a trickle

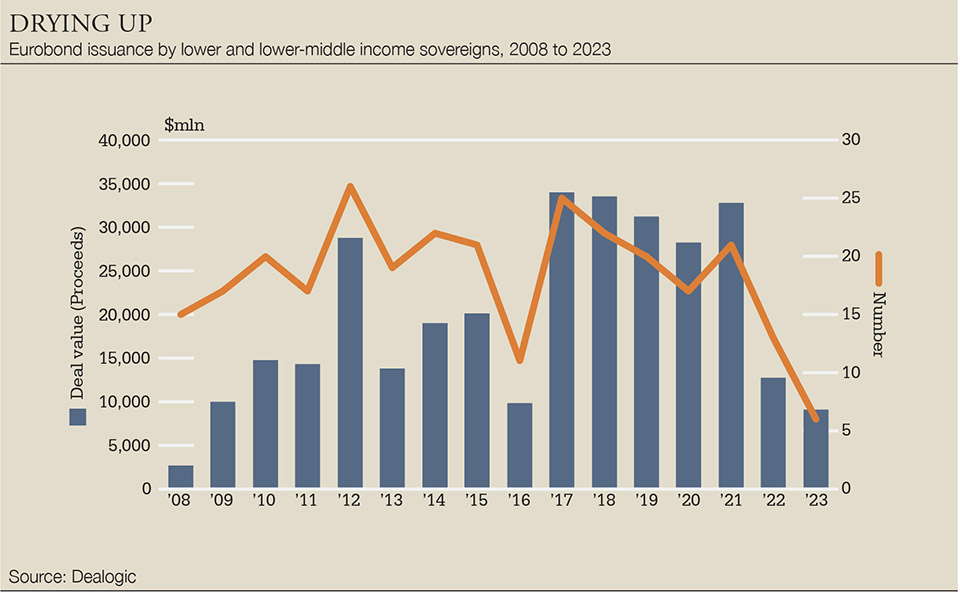

In the early 2000s, few states that the World Bank classes as low- or lower-middle income had access to international capital markets. But by 2020 bond issuance volumes from this category of countries – which investors sometimes term frontier markets – had shot up to more than $30 billion a year, according to Dealogic.

Now issuance from this group has plummeted again, dropping to $13 billion in 2022, according to Dealogic. Five countries in this income bracket issued Eurobonds in early 2023 including Egypt, Morocco and the Philippines, but none launched deals in the second quarter of 2023.

Due to higher rates and higher perceived risks, many buyers of frontier market debt have vanished.

“A lot of generalist investors are asking whether it’s necessary to take CCC-rated sovereign risk in parts of the world that are less familiar to them when they can get a good return in the US high-yield market,” says Nicholas Hardingham, an emerging market debt fund manager at Franklin Templeton.

In theory, not practice

Despite a rally in frontier-market debt between late spring and summer, investor retrenchment has left some sovereign bonds trading way out of line with their likelihood of default, providing an opportunity for specialists, says Hardingham. The problem is that wider investor misgivings may be self-fulfilling if countries are unable to access Eurobond funding at a reasonable cost.

Bankers say the market remains effectively shut for almost all African sovereigns. Those not yet restructuring – such as Kenya, Angola and Nigeria – could issue in theory, but they may not be able to do so in practice when most of them would still be paying more than 12% for 10-year debt.

With restructuring processes taking an unusually long time, another key default would cause long-lasting difficulty in accessing commercial borrowing.

“What’s happened so far could be explained away by Covid, but if Kenya restructures, that’ll risk shutting off most of the rest of Africa from the bond markets for years to come,” warns AJ Mediratta, managing partner at Greylock Capital Management in New York.

It took Zambia two and a half years just to get to an agreement in principle with the CF creditors – before it even started negotiations with commercial creditors. Restructuring experts say this is an exceptionally long time to remain in debt distress and the economy has suffered as a result.

Ethiopia, which faces a $1 billion debt maturity in December 2024, has even less to show for its request for help under the CF, something Addis Ababa blames only partly on the Tigray war. In Chad, CF creditors agreed last year that debt relief was no longer needed due to high oil prices and that they would reconvene if that changed.

These delays help no one, least of all the debtor nation, says Ian Clark, a London-based partner specializing in sovereign debt restructuring at law firm White & Case.

“Development and social goals are set back by these delays,” says Clark. “The creditors don’t get cash flow and their recoveries are lower because of the impact on economic output.”

Although Zambia has paid a price for being a test case, its president, Hakainde Hichilema, has reportedly said that its agreement in principle could be replicated elsewhere, heralding a new global dynamic in creditor negotiations.

Announced during a Paris summit organized by the French government – and after a visit by US treasury secretary Janet Yellen to Zambia earlier this year – the deal would allow a 40% reduction of the present value of $6.3 billion of external debt. According to the Zambian finance ministry, that will be achieved through an average maturity extension of 12 years and a reduction in interest rates to only 1% for the first 14 years.

But the wider difficulty of dealing with the latest wave of sovereign debt distress is not solved, nor will it be easily, in Clark’s view.

Sovereign debt negotiations are by nature extremely complex.

“An insolvent company is restructured in accordance with insolvency rules in a particular country, and if no consensual agreement is reached, the company is liquidated and there’s a process for that,” says Clark. “In a sovereign context, there’s no such overarching insolvency system, so the only solutions that can be found are through negotiation.”

These negotiations have become even harder lately because of the rise of new geopolitical tensions and changes to the structure of the global economy since the last emerging-markets crisis. And, in addition to the rise of China, private creditors are now mostly bondholders, instead of a tighter set of banks.

“The process is like three-dimensional chess now,” says Lee Buchheit, a retired lawyer and legal academic with a long history in sovereign restructuring. “That has complicated the process of debt restructuring in ways that I don’t think people predicted 10 years ago.”

In terms of the shift to bonds, the spread of collective action clauses after the early 2000s has helped prevent holdout commercial creditors from scuppering deals.

On the other hand, tensions around Ukraine and Taiwan have made even basic cooperation between China and Western creditors harder. Difficulties in reaching agreement on the language used to talk about the Ukraine war has made it harder for the G20 to produce joint statements this year, for example. Partly as a result, US hopes for a formal G20 statement acknowledging Zambia as a precedent for Common Framework restructurings have been disappointed.

It was not entirely coincidental, according to a source involved in the discussions, that the Zambia deal in principle happened in a window of relative rapprochement, shortly after visits to China by US secretary of state Antony Blinken and French president Emmanuel Macron.

“It helped the Chinese agree to a deal that could otherwise have been perceived to have been made under the pressure of the West,” says the source.

Although the G20 initiative remains the best chance of keeping China involved in multilateral debt restructurings, there is little prospect of it joining the Paris Club, which, with some obvious justification, China sees as a legacy of Western dominance.

By comparison to the Paris Club, the CF seems more transitory and less cohesive. First formed in the 1950s, the Paris Club is normally chaired by a senior official at the French finance ministry; it produces annual reports and frequent press statements. The Common Framework, by contrast, lacks even its own website. It appoints co-chairs for each restructuring from the Paris Club and one non-Paris Club G20 member.

All this means a restructuring by Kenya, for example, could be extremely tricky.

Choked by loans

A decade ago, Kenya agreed a $5 billion financing package for a railway stretching from the port of Mombasa 500 kilometres inland to Nairobi, using borrowing from the Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank). But the use and economic impact of the railway have been disappointing – amid allegations of fraud by Kenyan officials – and it has become another symbol of the era of all-too-easy borrowing. Debt from the railway now accounts for about half of Kenya’s bilateral borrowing, as well as a large chunk of its overall external debt.

Why Ghana and Sri Lanka’s restructurings may be faster than Zambia’s

Zambia’s restructuring was difficult in part because, as a relatively low-income country, it had to ask for an unusually high cut in the present value of its debt – almost 50%. To help smooth the acquiescence of creditors, the deal includes a novel arrangement whereby the interest rates will increase and the maturity will be brought forward if its debt-carrying capacity improves by more than the IMF and World Bank baseline scenario.

Borrowing from Chinese creditors constituted 43% of Zambia’s gross national income on the eve of its default, compared with 10% in Africa as a whole, according to research from Johns Hopkins University.

Purely private-sector restructurings have tended to be much quicker, according to Fitch Ratings, than those including large amounts of public-sector debt.

Delays

Ghana does not enjoy an especially large amount of goodwill on its commercial creditor committee, according to one member of it. It has been harder for Ghana than either Sri Lanka or Zambia to blame its problems on a previous government, says the creditor. A restructuring of local-currency debt has added complexity and brought more delays in Ghana.

This was something Zambia did not have to do – but it is becoming an increasingly common feature of sovereign debt restructurings.

Borrowing from Chinese creditors is relatively low in Ghana, at less than 10% of gross national income, according to the Johns Hopkins research.

From Ghana’s request for a restructuring under the G20’s Common Framework, it still took China and the Paris Club five months to offer what the IMF calls financial assurances, allowing a first tranche of IMF funding. That is longer than the roughly two months that was previously standard, when the Paris Club acted on its own – although in Zambia’s case, it took more than a year.

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka is not part of the Common Framework for restructuring, which was designed for lower-income countries. Indeed, Chinese lenders to Sri Lanka are negotiating separately from India and the Paris Club countries, which have formed a common creditor committee. It took Sri Lanka’s official creditors until early 2023 to offer sufficient assurances to unlock IMF funding, eight months after its default.

But as a higher income country than either Zambia or Ghana, Sri Lanka is supposed to be able to carry a much higher debt-to-GDP ratio. It has asked for relief including a 30% reduction in domestic and external dollar-denominated debt, well below the 49% Zambia requested on its external debt.

Guarantees over the railway debt left the country “choked by loans”, transport minister Kipchumba Murkomen told Kenya’s parliament last October, after a change of president.

According to Murkomen, Kenya should renegotiate the railway debt and ask for a longer tenor.

“It becomes impossible to pay that loan with revenue that comes from the railway,” he said.

Because of this, Eurobond holders could argue the railway debt should be included in any sovereign restructuring.

On the other hand, China could claim that the railway is a revenue-producing asset and that the bigger problem is the Eurobond maturity, says Brad Setser at US think tank the Council on Foreign Relations.

Collateralization mechanisms such as an escrow account established for collecting revenues from the project, as part of the Eximbank loan, would be among the points to haggle over, according to a sovereign debt adviser active in Africa.

Meanwhile, beyond geopolitics, there are the practical complexities of including China in multilateral restructurings. Many say that the lack of transparency in China’s lending to the developing world is a big challenge. Internal bureaucracy and the range of different actors in China don’t help. Experience of dealing with public-sector lenders in China has been lacking in the West.

Just finding where the debt lies and who to speak to can take a long time, says another adviser who has worked on recent restructurings.

There are some reasons to be optimistic, however.

Zambia has been a uniquely difficult restructuring, firstly because the IMF deemed its debt-carrying capacity to be exceptionally low and, secondly, because China accounts for an unusually large proportion of Zambia’s debt.

Setser and others ultimately expect Ghana’s restructuring to be much easier than Zambia’s because its level of Chinese debt is much lower. Reaching an agreement in Sri Lanka should also be easier than in Zambia, according to Setser, because Sri Lanka has a higher debt-carrying capacity.

The other reason that some in the restructuring world think debt workouts will be easier after Zambia is that the difficulty of its restructuring has made it a useful learning experience both for China and the West.

The last two years have allowed the Paris Club to get to know what it takes to persuade creditors of new importance, such as China, to participate in multilateral debt restructurings, says Paris Club secretary general Philippe Guyonnet Duperat.

“The fact that we are working together in Zambia and that we have worked together on Chad helped us convince other creditors that we needed to move forward quickly in Ghana,” Guyonnet Duperat tells Euromoney. “Once you have the base of an agreement in one country, you can refer to previous cases and build on common experience and practice.”

China lesson

One lesson that seems to have been widely learned over the past two years is the extent to which China will resist a write-down on the principal or debt haircut.

Those involved in restructuring talks with China give various reasons for this, including how the preservation of principal reduces the cost to the finance ministry of recapitalizing state banks because of the accounting treatment of the loans. Others say it is also to do with personal risks to the relevant Chinese officials if they were to admit to losses.

Suriname adds to pressure for change at the IMF

The IMF is a central actor in sovereign restructurings due to its provision of emergency funding and because its debt sustainability assessments largely determine how much debt relief countries request.

But creditors and advisers involved in restructurings including those of Zambia and Suriname – which both began around three years ago – complain that the IMF’s approach has not always helped speed things up. In Suriname, the Fund’s projections were far too pessimistic and would have needed Chinese banks to take a 30% nominal haircut, resulting in a refusal by China to negotiate, according to a source involved.

Suriname agreed a debt restructuring in principle with bondholders in May this year, including a value-recovery instrument tied to royalties relating to recent oil discoveries and a coupon reduction. Yet Suriname has still to conclude a deal with its Chinese bilateral lenders.

Both Chinese official lenders and international bondholders have called for an earlier sharing of the IMF’s economic projections and debt analysis. Others have argued for deadlines over how soon creditors should start talking and how long negotiations should last.

Speed

Retired restructuring lawyer Lee Buchheit further suggests reforming the IMF’s practice of waiting to disburse funding until it gets what it calls “financial assurances” from bilateral creditors – the formal indication that they will negotiate a restructuring on the Fund’s terms. He thinks this unnecessarily slows things down as it isn’t legally binding and is a relic of the 1980s when commercial creditors were mostly banks not bondholders.

After a first meeting of the new Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable alongside the G20 in April, the IMF and World Bank issued staff guidance on sharing macroeconomic analysis and debt sustainability assessments earlier in restructuring processes. It is hoped this will help speed up the internal bureaucracy needed before public-sector Chinese lenders can enter creditor committees.

The roundtable further said there would be more work done on potential changes around cut-off dates, IMF lending into arrears and the perimeter of what is restructured, including local-currency debt.

“In 2020 and 2021, the tone at the IMF was much more aggressive towards creditors,” says Thys Louw, emerging-markets portfolio manager at Ninety One.

Now the Fund is taking what Louw calls a more collaborative approach than it took during its 2020 assessment of Zambia’s debt sustainability.

The IMF has demonstrated a “more relaxed and friendly approach”, according to Louw, in programmes this year, which has helped give Pakistan and Kenya more time to stave off default.

Whatever the reason, Zambia dodged this aversion to debt haircuts by terming out and reducing interest rates to arrive at the same place in terms of the reduction in net present value. But Zambia’s restructuring has still been a shock for China, according to a source in the talks, because it was pushed into a negotiation that included the IMF and other world powers. Previously it had simply offered debt suspensions on a government-to-government basis – even if that meant Eurobond holders continued to be repaid.

“Remember that China has lent the money either to lock in supply of commodities like oil, copper and bauxite or to win friends and influence people,” says Buchheit. “It lends money as part of a geopolitical effort to develop a multi-polar world. If those are the motivations for you lending the money and you wind up restructuring the debt together with other bilateral creditors, you dilute the benefit. It is no longer China and, for example, Mauritania striking a deal. It is rather Mauritania and its collective bilateral creditors.”

Many observers point to China’s method of dealing with debt distress before Zambia – simply by suspending the debt for a couple of years – and how this is much the same as the US banks’ approach to Latin American sovereign borrowers in the 1980s. Those loans were eventually written down and restructured into bonds backed by US Treasuries under the Brady Plan.

Chinese state banks implemented a similar standstill in 2020 in Angola, by far Africa’s biggest borrower from China. Again, this was on a bilateral basis, albeit as part of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative launched by the G20 at the start of the pandemic. Although the IMF accepted the standstill as part of the basis on which to increase its funding, the lack of longer-term debt relief means the country could face trouble repaying its debt in the next oil price crash.

Some see rolling currency swaps arranged by China’s central bank as, in effect, another way to term out Chinese lending in countries such as Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

The Zambia restructuring is, therefore, an important breakthrough – even without formal Chinese acknowledgement that it can be a precedent.

“It’s been a big change for China to accept some real net present value debt relief and to do so in a transparent way, rather than through direct consultation and dialogue only with Chinese lenders, where only China knows the final terms,” says Setser.

China may be concerned about the way it has been seen to have delayed debt restructuring deals in regions such as Africa, where it’s supposed to be a champion of developing countries. Commercial creditors may also need to think about the way in which they would be seen to be holding things up – not least given the threat of them being forced to participate in restructuring deals under a new legal framework in the US and potentially in the UK.

Yet there are still doubts about quite how much the lessons of Zambia and elsewhere will lead to an easier restructuring environment.

“In November 2020 when the Common Framework was announced, that was seen as a major advance,” says Buchheit, with an air of scepticism. “It appeared to be a commitment by China to negotiate together with its bilateral creditor colleagues, jointly. That got bogged down very quickly. There are hopes now that China is becoming more comfortable with that process, but we shall see. It’s possible that’s how it plays out.”

Although the Zambia agreement gave Macron the chance to style the Paris summit as a success, there was still a lot to do on Zambia’s restructuring. Moving from an agreement in principle to signing the memorandum of understanding between official creditors took longer than expected and failed to happen before the northern hemisphere’s summer holiday period.

Negotiations with commercial creditors could also be complicated by $1.75 billion of claims from Chinese export credit agency Sinosure, which were previously classed as official.

The lesson of Zambia

Part of the difficulty of including China in restructurings alongside Western public-sector lenders is the hazier distinction between official and commercial lending in China. All the big Chinese commercial banks, for example, are state-owned.

The multiplicity of lenders and decision makers in China – the ministry of finance and central bank, as well as Eximbank and China Development Bank – has also made getting agreement from China harder, according to restructuring advisers. In the Paris Club there is only one representative per country.

But the emergence of non-Western creditors at the forefront of developmental lending arguably brings a far deeper problem relating to the global institutional framework for dealing with sovereign debt restructurings. That is because of the perception by China and others that the IMF and World Bank themselves are Western-led institutions and to be trusted just as little as Western bilateral lenders.

“The Chinese regard institutions like the IMF and the World Bank as essentially carrying out the policy of the Western powers,” says Buchheit. “They don’t want to feel themselves subject to the dictates of people like the IMF.”

Because of this distrust, distressed sovereigns will do better if they come up with their own macroeconomic expectations and debt-relief needs, which they can then present directly to China instead of relying on the IMF’s analysis, according to a source in the Ghana restructuring.

Direct talks with China helped Ghana secure enough official creditor commitment to release emergency IMF funding in May, much quicker than in Zambia.

“Yes, the lesson of Zambia was learnt,” says the source. “It’s been handled with better care in Ghana. China felt like it was more in a bilateral discussion – not in the substance but from a diplomatic point of view.”

China’s misgivings about the Western-led nature of the process are understandable. Compared with the US and Europe, its voting weight in the IMF is far less in sync with its current share of the global economy.

However, this dynamic may help recalcitrant bondholders pretend that the rise of China is the problem. It has also given China an excuse to drag its feet and insist on its own stream of talks, according to Setser.

“I don’t think China has been a difficult player because they’re underrepresented at the IMF,” he says. “I think they’ve been a difficult player because they don’t like taking losses and they don’t like transparently taking losses.”

It is still important to avoid debt restructurings that could seem to China and other new creditors like “others are being generous with their money,” says Baqir at Alvarez & Marsal.

Getting these new creditors involved in talks to improve the restructuring framework was largely the point of a new Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable launched this year. It is co-chaired by the heads of the IMF and World Bank, alongside Indian finance minister Sitharaman – in line with the 2023 Indian presidency of the G20. It also includes representatives of debtor countries and commercial creditors.

But the wider problem of negotiating restructurings across the East-West divide remains, and not just due to resentment in China. For Western politicians too, it is often popular to blame problems on China.

In the case of Zambia, China seemed in June to have dropped its earlier suggestion that multilateral lenders should take losses alongside bilateral creditors. That breakthrough happened after the World Bank indicated, as part of the April roundtable, that it would step up support to low-income countries at risk of debt distress through higher concessional lending and grants. As money is fungible, this would effectively reduce the need for debt relief by China in countries such as Zambia.

Some think China’s suggestion that multilateral lenders should take losses was simply a bargaining strategy, as it would be a large and possibly destabilizing break in precedent given the extent to which multilaterals provide new money and get funding cheaply because of their preferred creditor status. Western governments resisted the idea.

Concessions

However, it is not clear that China has reneged on the wider principle of multilateral losses in debt restructurings, nor is it clear exactly what finance the multilateral banks will provide that they wouldn’t have provided before. Zambia, for example, will receive World Bank funding entirely in the form of grants from this summer, not because of the restructuring agreement but through longstanding World Bank policies around poverty and debt distress, in this case to do with Zambia’s default and the reduction in its gross national income per capita since 2019.

In any case, stepping up multilateral flows of concessional loans and grants is important far beyond easing East-West tensions in debt restructurings.

Multilateral bank disbursements are today far lower relative to the GDP of recipient nations than 20 years ago. Moreover, after Covid and the Ukraine war, many developing countries are struggling to afford imports of basic products such as food and fuel, let alone capital investment.

In March this year, the G20 set up an expert group on strengthening multilateral development banks, co-chaired by former US treasury secretary Larry Summers and NK Singh, the Indian politician and former civil servant. Reporting in late July, the group recommended capital increases for multilateral lenders including the World Bank. It warned of a near-term funding crisis facing the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) and urged a tripling of funding for the poorest countries under the IDA by 2030.

With demand for multilateral lending rising, not least because of the need to invest in climate transition, any recapitalization of multilateral lenders such as the World Bank will itself require delicate negotiation between the US, China and others. The G20 leaders’ joint statement in September backed reform and expansion of the World Bank and others, but details were lacking.

The World Bank announced some initial steps in mid July, including a shift to a funding structure based more on guarantees and allowing it to make greater use of hybrid and callable capital. This sort of financial engineering reflects the difficulty of getting wealthier nations to agree on bigger capital commitments, especially in the form of non-repayable aid rather than more debt, says Oxfam policy officer Didier Jacobs.

“Two billion people are living in countries that shouldn’t borrow more,” says Jacobs. “That’s a huge problem as climate change requires a lot of capital investment. We need solidarity with aid.”

Financial colonialism fear adds to restructuring headaches

“We underestimate Beijing’s financial colonialism at our peril,” warned a recent headline in the UK’s Daily Telegraph. China, the article said, appeared to have deliberately set debt traps in poor countries with the aim of securing natural resources and strategic assets such as ports.

With debt distress rising in the developing world, it is a view increasingly heard in the West, especially among those in the UK and US more inclined to a hawkish position towards China.

The strategically located Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka is often given as a prime example, after a Chinese state-owned port developer took ownership as part of a debt-for-equity swap in 2017.

Is it all part of a plot by China to grab natural resources and military bases around the world?

The idea that China is engaged in so-called debt-trap diplomacy has not always stood up to scrutiny. Looking at Kenya’s Chinese-financed Standard Gauge Railway, researchers at the China-Africa Research Institute of Johns Hopkins University in the US argue the security features of loans by China Export-Import Bank – one of the two biggest Chinese policy lenders – aren’t much different from those of Western banks. This includes off-take agreements, escrow accounts and sovereign immunity waivers, the research says.

The same research institute argues that Sri Lanka had a choice when it privatized the Hambantota port because the project debt was still in its grace period. In other words, it was not a foreclosure.

Complexity

Nevertheless, the collateralization of Chinese-financed infrastructure complicates debt restructurings and not just because of the way that in the West it has politicized China’s role in debt distress. Restructuring advisers say Chinese banks’ security clauses over infrastructure projects they have financed add to the bargaining chips that China puts down, lengthening the time needed to thrash out the details of restructuring deals.

Zambia, for example, has borrowed from Chinese state banks for infrastructure such as dams on a project-finance basis, whereby the project’s revenue flows to an escrow account.

After Zambia’s 2020 default, the Chinese side of restructuring negotiations suggested that some of this project debt should be excluded from debt relief. According to a source in multilateral restructuring talks in Zambia, that argument needed to be heard and factored into the overall amount of debt relief, albeit in a marginal way, adding to the complexity of the negotiations.

Similar discussions would be needed over Kenya’s railway loan if it asked to restructure its sovereign debt, the source says.

Oil-exporting countries that rely on China as a buyer have in some cases borrowed heavily from Chinese state lenders based on collateral arrangements linked to oil revenues. Sovereign borrowing based on commodities is easier when the exporting firm is state-owned, such as a national oil company. Angola, for example, is by far China’s biggest borrower in Africa and has Africa’s highest number of projects built and financed by China, according to the Johns Hopkins researchers.

Recently, high oil prices have helped countries such as Angola to avoid default. But if the strength of collateral based on oil has made it easier for oil-exporting countries to borrow from China, that has also created more doubt about whether spending from those loans has been on the most urgently needed projects.

How much this is part of a grand strategy to claim vital infrastructure and natural resources is uncertain. Those active in debt negotiations with Chinese banks have no doubt that the main aim is to be repaid not to realize the collateral, which in any case is often not enforceable in practical terms.

That might suggest that the excessive growth of Chinese bank debt in the developing world over the past decade is less down to grand strategy than a lack of experience in developmental lending and – rather like in China’s domestic property sector – insufficient oversight.