IT IS PERHAPS appropriate that Sistema, one of Russia’s largest private companies, held its investors’ day in June at London’s Royal Academy of Arts at Burlington House. More than one observer at the Palladian mansion noted the similarities between the building, crammed with serious-faced young Russians charging around engrossed in their BlackBerries, and the opulence of St Petersburg.

More generally, the enormous contingent of Sistema staff, bank analysts and investors – many of whom were Russian – were a reminder that London is increasingly graced by well-heeled Russian expatriates: indeed, it is hard to walk down any of London’s smarter streets these days and not hear Russian spoken. The country’s elite has truly taken the city to their collective heart and its companies have flocked to the London Stock Exchange.

The growing affection of Russians for London and the willingness of London-based investors to invest in their companies has come under increasing pressure over the past year. Still, scarcely a day goes by without the announcement of a mega-IPO from Russia destined for London, but concerns about corporate governance and business practice in Russia have become the backdrop to each successive deal and investors have become ever more sceptical.

Moreover, the political detente between Russia and the west that followed September 11, 2001 is long gone. Europe and the US have become increasingly concerned about Russia’s use of the power to withhold or beef up the price of energy resources to bully its neighbours. And on the day that Sistema entertained investors at Burlington House, president Vladimir Putin raised the spectre of nuclear war in Europe as a consequence of the US plan to build a missile defence shield in Poland and the Czech Republic.

In particular, relations between the Kremlin and London have become strained following the murder of a former KGB spy in London and Moscow’s refusal to hand over the chief suspect, who is widely alleged to have acted with the tacit consent of the Kremlin. In July, the dispute escalated, with the UK expelling Russian embassy staff in protest and Moscow retaliating by expelling British embassy staff. There may be consequences for the easy flow of capital and people between the two countries.

A reluctant leader

Sistema was part of the first wave of IPOs from Russia that followed the listing of Lukoil in 2002 – albeit with a three-year lag. It floated in London in 2005, raising $1.2 billion, and has chosen the London Stock Exchange to list the majority of its subsidiaries, including real estate company Sistema-Hals, electronics manufacturer Sitronics and mobile telecoms group Comstar. The company has relished being a pioneer – although it has no plans to list further units – but has had to bear the brunt of generalized attacks on Russian companies for their perceived loose standards of corporate governance.

Vladimir Evtushenkov, chairman of the Sistema board, founder of the company in 1993 and owner of 63.1% of the shares – and one of Russia’s richest men, with a net worth of more than $8 billion by some calculations – gives the impression of not being especially happy to play the role of ambassador for Russian business and defender of its corporate governance standards. Described as having a dry sense of humour by those who know him, Evtushenkov, speaking through an interpreter, is terse and staccato in his responses, although, to be fair, he had spent much of the day repeating the same points in one-on-one meetings.

For example, asked what benefits Sistema and its subsidiaries have derived from being listed on the London Stock Exchange, Evtushenkov replies curtly: “None”, before adding: “We received money that we needed for our development.” Evtushenkov dismisses the idea that such an attitude could be perceived as insulting to investors, who might welcome more of an attachment to generating shareholder returns and increasing transparency. “Investors understand that being listed is not a panacea for a company’s success,” he says, before back-pedalling somewhat.

“Being listed does bring a certain discipline and makes a company more transparent and behave according to international standards. It also makes high demands on a management team,” he says. “But overall, it has both advantages and disadvantages.” He believes that on the positive side it should result in a company having a more focused development strategy – although this is not immediately apparent in the case of Sistema, of which more later.

Evtushenkov’s brevity – he is known to adopt the same approach in conversation with investors as with journalists – might be interpreted by some as arrogance. But such aloofness can perhaps be justified by his company’s results. At the end of the first quarter of 2007, Sistema’s consolidated revenues were 44% higher at $2.7 billion than a year earlier and operating income was up by 87% to $728.5 million, with an increased operating margin of 26.9% and organic growth for the preceding 12 months of 38%. Even in the booming Russian economy – GDP growth is expected to be well over 7% in 2007 – those are impressive statistics.

What is Sistema?

Sistema pointedly describes itself as Russia’s leading consumer services company. But what does this actually mean? Asked to define what consumer services entail, Evtushenkov initially declines to answer – he merely shrugs and looks expectantly for the next question. When challenged, he offers nothing more than an assertion that consumer services are what Sistema is “in principal” involved in.

In reality, Sistema is a diversified conglomerate: it is primarily involved in telecoms, technology and real estate and has sizeable activities in banking, retail, media, tourism and radio, as well as smaller businesses in pharmaceuticals and medical services. Most recently, it has moved into the oil business, with acquisitions that have raised eyebrows among some observers.

Why Sistema is so reluctant to acknowledge its nature as a conglomerate is a mystery: after all, many of the west’s largest companies started out as disparate groups of companies with little or no synergy between them. Moreover, Evtushenkov is on record as saying that the disparate nature of many Russian companies stems from the chaotic privatizations of the early 1990s and that they will iron themselves out in due course.

Perhaps Sistema’s shyness in recognizing its true nature stems from its role as a figurehead for Russian companies on the London Stock Exchange: it is eager to chime with western analysts and the business orthodoxies of “focus” and “synergies”. The problem with claiming to subscribe to such notions – and using the consumer services tagline – is that it doesn’t square with the reality of Sistema and therefore defeats the point.

For example, to many observers, financial services might be considered a central activity for a consumer-focused group, especially in Russia, where loan growth rates are around 30% a year and the insurance market is growing by 25% a year. Yet Evtushenkov says that financial services are not a core element of Sistema’s business future. Moreover, the company’s recent activities in the financial services sector are hard to explain and raise questions about its long-term strategy.

In February, Sistema sold its 49.17% stake in Rosno, its insurance unit in Russia, to its partner in the venture, German insurance company Allianz, for $750 million, giving Alliance 96.53% of the company. Rosno, which was established in 2001, is number four in the Russian market and, by all accounts, a solidly run and profitable operation: gross premiums written, the preferred measure of achievement in insurance, increased by 70% in 2006 to reach $787 million.

Why did Sistema choose to exit such an attractive market? “We could not develop Rosno jointly with Allianz because of a conflict of interest: someone had to leave,” says Evtushenkov. “Allianz needed consolidation of the business and management of the company because they are strategists [by nature]. We also wanted control of the business and therefore a conflict arose.”

The original agreement between Allianz and Sistema stipulated that Sistema had the option to buy out its German partner. However, during discussions on the future of Rosno, Sistema decided to back off and instead invited Allianz to convince it that it was worthwhile selling out. “We exited Rosno not because we were given an offer that we couldn’t refuse but because we had no alternative – one of us had to give way, otherwise [Rosno] would have suffered from the conflict,” says Evtushenkov. “We believed that a good relationship with Allianz would, in the long term, be important.”

Some observers have suggested that Allianz got the better of Sistema in negotiations when, given the Russian company’s position of strength, it should have emerged on top. Moreover, there have been suggestions that the three-year non-compete agreement that Sistema signed was unnecessarily restrictive and that Allianz would have been satisfied with a shorter deal. All Evtushenkov will say is that it is “unfortunate that Sistema is not in the insurance market” and that it won’t be for three years.

The other element of Sistema’s activities in the financial services market is the Moscow Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which provides retail and corporate banking services and which enjoyed a 59% year-on-year increase in its loan portfolio to $1.6 billion at the end of March 2007. With 95% ownership, Sistema is clearly not going to face similar problems to those at Rosno in relation to a partner, but how serious is the company about retail and corporate banking? Would it be open to the right offer for MBRD?

“We have no need to sell MBRD and the bank has no strategic foreign partners,” says Evtushenkov. “Therefore, in the meantime, we plan to develop our bank further. What will happen after that? Who can say – we live and learn from our experiences all the time.” Evtushenkov says that there was no overlap between Rosno and MBRD on areas such as bancassurance products and therefore the sale of Rosno will have no impact on MBRD’s development.

Is Sistema just an opportunist investor?

Sistema’s 2006 annual report spun the Rosno sale as demonstrating “the ability of Sistema not only to profitably buy into assets but also exit profitably”. But does that mean Sistema is destined to become a portfolio investment company with an ever-changing selection of assets? Its activities in the oil sector would suggest such an approach could become more dominant.

In August and November 2005, Sistema spent a total of $599.7 million buying stakes in seven oil companies that dominate the oil-rich southeastern Russian republic of Bashkortostan, ranging from 21% in Bashneft to 27% in Novoil. When combined, the companies’ production makes them Russia’s third-largest oil refiner. At the time, there was considerable disquiet about the purchases: they came just months after Sistema had listed and pitched itself as a telecoms-focused group and – as is often the case in Russia – there were concerns about the legality of the assets and the fact that they had been acquired from the son of the region’s president.

Sistema has defended the purchases as a good use of funds. “If you were offered a substantial amount of money in a short period of time and you call yourself a businessman, what are you going to do?” asks Evtushenkov rhetorically. “One always has to choose between the desire to earn money and the potential displeasure of your partners or investors.”

Certainly, the boom in oil prices has made the oil companies a wise investment; Evtushenkov claims a trebling of the value of the initial investment. But more than two years on, it is unclear what role they will play in Sistema’s future. Evtushenkov has recently been quoted as saying that Sistema would like to increase its stakes in some of the oil companies to become a controlling shareholder: to what end?

“Oil is a complex asset and therefore it is difficult to pinpoint what will happen,” says Evtushenkov. “There is a disparity between our desires and wishes and our capabilities in the sense that we would like to be controlling shareholders but at this time we cannot achieve it. We cannot predict the future, but one of the potential scenarios would be to merge the companies.” Some observers believe a partial listing would follow.

The real core of Sistema

Despite efforts to diversify, most of Sistema’s revenue still comes from its listed telecoms companies, which are headed by Russia’s largest mobile phone firm, Mobile TeleSystems, listed in New York in 2000. In the first quarter of 2007, the company derived 76% of its business from telecoms – down from 81% a year earlier but still clearly the mainstay of Sistema’s operations. Consequently, it is in the telecoms market that Sistema’s conduct matters most and – not coincidentally – where it has been most aggressive.

|

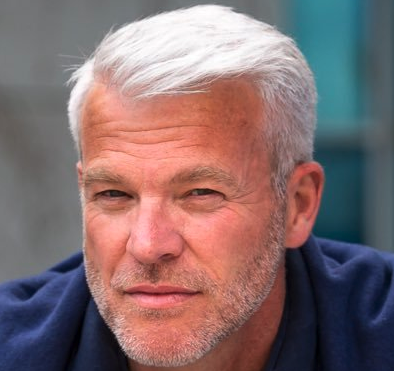

Vladimir Putin (l) and Vladimir Evtushenkov (c) visit a Russian chip-making factory. Some question the closeness of the Sistema boss to the Russian president, though Evtushenkov remains coy about whether or not the relationship pays dividends |

One of Sistema’s most recent actions in the telecoms market was the purchase of 25% plus one share – a blocking stake – of state-controlled telecoms holding company Svyazinvest, thought to be worth close to $7 billion, in December 2006. Svyazinvest is important because it not only owns seven regional telecoms companies – four of which also have mobile operations – but also 23% of the Moscow City Telephone Network (in which Sistema already had a stake and now holds a total of 33%) and long-distance carrier Rostelecom, which despite losing its monopoly on long-distance and international calls last year remains that market’s dominant player. The acquisition of the stake in Svyazinvest was complex, involving call options between various Sistema affiliates, but overall it cost Sistema about $1.3 billion in cash, as well as the unidentified cost of a call option on 11% of Sistema subsidiary Comstar at 5% below the current market price for a year offered to the vendor of the Svyazinvest stake. The move realized a long-held ambition for Sistema and was flagged up for its IPO in 2005. “Svyazinvest was a strategic investment for Sistema,” says Evtushenkov, who has always been candid about his desire for control of the monolithic state enterprise.

The problem for Sistema is that there is no date for the privatization of Svyazinvest. In mid-July, Russian economy minister German Gref listed several forthcoming privatizations stretching as far as the third quarter of 2008 but said that there was no deadline for Svyazinvest’s sale. However, in the same week Russian IT and communications minister Leonid Reiman confirmed that privatization would be an eventual goal for the entity. “We only know that there will be no privatization in 2007 or 2008,” says Evtushenkov.

The Russian government – in its typical blow-hot-blow-cold way – recently raised the possibility that Rostelecom could be stripped out of Svyazinvest, substantially lowering its value to Sistema. Similarly, at the end of June, there was talk that Svyazinvest could dispose of its mobile operations because of the absence of long-term growth opportunities given that it does not hold any third-generation mobile licences. In answer to the suggestion about Rostelecom, but applicable to both possibilities, Evtushenkov says that nothing has been decided and, in any case, as a shareholder Sistema’s agreement would be required. “If such a move is disadvantageous to us then it won’t go ahead,” he says.

Why chase mature markets?

Despite rapid growth in all the sectors that Sistema operates in within Russia, the company is eager to expand internationally. At Mobile TeleSystems, 30% of the company’s revenues already come from abroad. “The trend is quite clear: the share of revenue from foreign [non-Russia] markets will continue to grow,” says Evtushenkov. “That increase will come from a number of markets, but primarily from developing countries both in central and eastern Europe and in Asia.”

Although Sistema’s main overseas focus might well be developing markets, it has also made plenty of noise about wanting to get into the western European telecoms markets. Why would Sistema want to be involved in mature markets, when it has rapidly growing markets on its doorstep? “It never does any harm to show interest in a wide range of opportunities,” says Evtushenkov.

In recent months, the business press has published a steady stream of articles about Sistema’s intentions to buy a stake, swap shares – or even merge with – Deutsche Telekom. One mooted way for Sistema to gain a share of Deutsche Telekom would be for German state holding company KfW, which owns 31.7% of Deutsche Telekom, to sell out. However, German government ministers have consistently said that this stake is not for sale. More generally, there is substantial hostility – primarily on the ground of national security but also, no doubt, for reasons of national pride – to a Russian company buying one of Germany’s “crown jewels”.

Evtushenkov admits that he thinks it unlikely that any European government or the US would allow a Russian company to buy a major industrial asset. So, is there any truth in the myriad press stories – many of which quote Sistema chief executive Alexander Goncharuk – that the company is intent on acquiring a stake in Deutsche Telekom and has held discussions to that effect? “The story was so attractive for all the parties involved that it had to have come from somewhere,” says Evtushenkov. “But for us, it is simply one of many scenarios – I wouldn’t read too much into it.”

One alternative to Sistema acquiring a stake in Deutsche Telekom that has also been extensively trailed in the press is the possibility of buying part of Telecom Italia from the Pirelli Group, which owns 80% of holding company Olimpia, which, in turn, holds 17.99% of Telecom Italia. A 30% stake in Olimpia, which is reportedly what was up for offer in the first quarter of this year, would give Sistema a 5% stake in Telecom Italia. Evtushenkov dismisses the suggestion that Sistema wants a stake in Telecom Italia, saying it is a “media fiction”, although Goncharuk has been quoted in numerous reports making it clear that Sistema is interested in the company.

Uncertainty is unwelcome

Evtushenkov is clearly a pragmatic man, willing to adopt different strategies in different markets. He is also a confident man, unwilling to turn down an opportunity simply because it doesn’t ring true with analysts and investors, and similarly willing to bide his time while the market catches up with his views on valuation. For example, he believes that Sistema’s real estate subsidiary, Sistema-Hals, is “seriously undervalued” and while it was important for the company to be the first listed Russian property developer, the parent company has no intention of reducing its 80% stake or exiting the market in the short term.

Such mavericks clearly have a role in business – especially in emerging markets, where wealth and political contacts can give a company critical mass in a new market (such as oil in Sistema’s case) almost immediately. However, it remains the case that markets abhor uncertainty, and Sistema’s inability to fully communicate its game plan has had negative consequences for the company.

When Sistema’s first-quarter results were announced, the company said that its unlisted businesses generated revenues of $150 million – an increase of 153% on the previous year and almost five times higher than the 35% increase enjoyed by Sistema’s telecoms business. But because of Sistema’s opacity – particularly, but not solely, in its unlisted businesses – its stock is widely believed to be undervalued by around one-third. It remains to be seen if a reorganization announced at the beginning of July that will bring the management and development of Sistema’s unlisted units together will result in a revaluation of the stock.

More generally, Sistema has undoubtedly been affected by cautious investor sentiment towards Russia as a result of concerns about the business environment in the country. Many observers believe this is becoming increasingly unfair and discriminatory – critics point to recent examples where western energy companies have effectively been forced to give up lucrative development concessions in favour of Russian companies as evidence. Evtushenkov is evasive when asked if Russia is a fair place in which to do business: “Give me an example of a country where the law is applicable, just and fair to everyone,” says Evtushenkov. “There are always two sides to every situation and the loser [always] believes that he is hard done by.”

Evtushenkov is more accommodating of investors’ concern about political relations between Russia and the west. “Of course, [the current disputes between Russia and the west] affect the business and, although you can’t attribute share price movement entirely to the political climate, it has held share prices back in Russia this year,” he says. He adds: “Who wouldn’t want a calmer tone to relations?”

Domestic politics could have major repercussions for Sistema as Russia approaches the March 2008 presidential elections, from which Putin is constitutionally barred from standing for a third term. Some observers are concerned that Sistema’s political connections – Evtushenkov is personally close to Moscow’s mayor Yuri Luzhkov and is reported to have a dedicated hotline to Putin on his office desk – could turn into a liability following the election.

What benefits does Sistema derive from these relationships? “It is hard to say,” says Evtushenkov. “Maybe we are lucky that no-one has stopped us from growing, but on the other hand, we do not the break the law and we avoid conflicts. So I don’t think that it would be right to say that our wonderful relationships [with government] bring us particular dividends.” So it would make no difference to the company if someone not loyal to Putin wins the election in 2008? “We are optimistic about the future,” says Evtushenkov. “We believe that the government should support companies like ours, not because we are good but because companies are resolving problems that are important for the country as a whole. It would be foolhardy to destroy such companies in order to satisfy short-term political ambitions.”