By Jonathan Breen

On the home page of the Cambodian securities regulator’s website, the wise words of legendary investor Warren Buffett scroll past endlessly on a ticker: ‘Invest only in companies you understand’, it says. And ‘Do not put all of your eggs in one basket’.

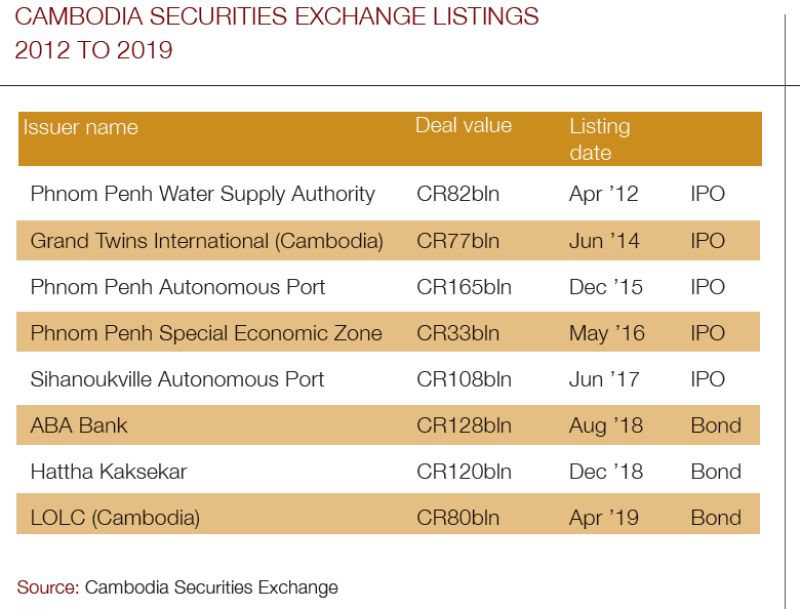

In Cambodia, where there are only five companies and three bonds listed on the country’s stock exchange, such mantras hint at a desired future.

But the Cambodia Securities Exchange and the authorities that regulate it are doing what they can to change that. The country’s largest bank announced in December that it had got the green light to list, while prospectuses for two new corporate bonds are on the desk of the regulator.

These bonds have the foreign investor-enticing touch of a guarantee by the Asian Development Bank’s Credit Guarantee and Investment Facility (CGIF).

The CSX is one of the quietest stock markets in Asia. It opened in 2011 and struggled to capture barely one IPO a year until the last listing in 2017 by Sihanoukville Autonomous Port, which bagged CR108 billion ($27 million), a record for the bourse. After that, the corporate bond market attracted more attention with Hattha Kaksekar’s CR120 billion debut issue in December 2018.

The goal is for both the stock and bond markets to begin growing in earnest alongside each other.

Three of the five listed companies are state-owned enterprises (SOEs): Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority (listed in 2012), Phnom Penh Autonomous Port (2015) and Sihanoukville.

For Bora Kem, investment manager at Cambodian fund Mekong Strategic Partners, SOEs don’t get the blood pumping enough for investors: in his view, more interesting private names are needed.

“It will take companies that are exciting,” says Kem. “What have been listed are the state-owned enterprises. There are some interesting macro things about them, but in terms of speculation or growth you don’t see it in those type of companies.”

More IPOs are expected within the next year, with as many as five by private companies in 2020, according to multiple market sources. Unlike the existing stocks, most of the soon-to-be issuers are small and medium-sized enterprises, says Shuzo Shikata, chief executive of SBI Royal Securities. SBI Royal is one of the six firms granted an underwriting licence by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Cambodia (SECC).

“The SECC has pushed us very strongly to support SMEs,” says Shikata. “They coordinate workshops often to introduce IPO candidates to securities firms, and we are one who has taken on SME IPOs.

“I believe it is very hard to find strategic investors for SME companies, so we are trying to launch some SME IPOs next year.”

The most important thing is how you educate people. Financial literacy is very important, to get people to understand the role of capital markets in driving the economy - Bun Yin, CIMB Cambodia

There are bigger IPOs on the immediate horizon, including one from the largest of the country’s 43 commercial banks. In 2018, the CSX granted approval to the holding company of Acleda Bank, the Acleda Shareholders Association (ASA), to issue and list bonds.

ASA had delayed issuing and instead considered listing Acleda Bank. And Cambodia’s central bank gave Acleda the go-ahead for an IPO in late November 2019.

The bank is marketing its listing as a ‘people’s IPO’, targeting public and retail investors, which could help to boost liquidity on the bourse.

“Our shareholders have unanimously agreed that the bank should become public to diversify our sources of funding and utilize the Cambodian capital market for our future growth,” says In Channy, Acleda’s president and group managing director, in a statement in December announcing the IPO plan.

“We would like to inform our customers and the public that Acleda Bank shares will be available for investment after getting further approvals from the CSX and the SECC. We will make public announcements on the date of [bookbuilding] and subscription soon.”

Raising their profile

Cambodia’s stock exchange, and its capital markets in general, suffer from a lack of public awareness and understanding about what they are and how the public can use them, hence the efforts by the CSX and SECC to raise their profile.

Hong Sok Hour, chief executive of the stock exchange, has been a driving force. But getting people on board has not been easy.

Hong Sok Hour, CEO of CSX

“We have many challenges,” says Hong. “At the first level, business owners in Cambodia do not know about the stock market. They have heard the word, the term, but they don’t know how it works for them. For them it still looks like some kind of gambling or casino. For many years we have tried to change that perception, to let them know more about this market and how it can help them grow.”

As Bun Yin, chief executive of CIMB Cambodia, sees it: “The most important thing is how you educate people. Financial literacy is very important, to get people to understand the role of capital markets in driving the economy.”

Another serious hurdle is that listing is synonymous with going public. And that requires a company to open its books for all to see, including the authorities. That’s a line that many Cambodian businesses will not, or at least at the moment cannot, cross.

Business owners “don’t want to use other people’s money to grow their business, they are afraid about other people knowing about their secrets or their financials, so they just want to grow organically with their own money,” says Hong.

The intention of the strategic investors is to hold the shares for a long time, to cooperate with the issuers. That is why liquidity is very limited - Shuzo Shikata, SBI Royal Securities

Cambodia has only been a country in its modern form for 27 years, since the United Nations moved in to help begin laying the foundations for a democracy. But between then and now there have been plenty of opportunities in the business world to get away with not playing by the rules.

“Most companies here, frankly, do not comply fully with their tax obligations,” says Hong. “They cannot go clean. Once they are listed, everything is on the table and the tax authority can see immediately that they have failed their tax obligations for many years. The tax authority can go back 10 years in the past and look at their books. That is the biggest obstacle for us.”

Hong says: “A few companies did realize the importance of raising money to grow their business, but many of them are still stuck with the problem that they cannot go clean now because of their past. They had bad practices in the past and they cannot clean it immediately. Or they have to compete with other businesses that are not clean, so they cannot go clean alone and stay competitive.”

Hong is trying to bring smaller issuers to the exchange, which could potentially list on its (for now) empty growth board.

“We are working with two potential companies,” says Hong. “Those are quite new companies, they were created two or three years ago. They are quite young, so I think we can list them [in 2020].”

Slow start

The exchange has had a very slow start, even by frontier market standards.

“We were supposed to list three state-owned companies when we launched,” says Hong. “Phnom Penh Water Supply (PPWS), Sihanoukville Autonomous Port and Telecom Cambodia, those were the most reliable companies at the time.

“We could only list PPWS, the others were not ready,” he adds. “Everything was not according to plan since the beginning. If we had started with three, then we should have had a lot of momentum for market development, but we started with one.”

Telecom Cambodia remains unlisted. Its IPO was delayed indefinitely after the company was caught up in an alleged embezzlement scandal.

The subsequent slow burn of the IPO market resulted in a familiar problem for new stock exchanges: liquidity.

Trading levels on the CSX are increasing and share prices with it, but the market has suffered from buy-and-hold strategic investors, which in particular handicapped some of the early listings.

|

Shuzo Shikata, |

“In 2016, we underwrote the Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone IPO, 80% was taken by institutional investors,” says SBI Royal’s Shikata. “The majority of them were transportation companies because they had business in the economic zone, shipping or import and export, things like that. So they believed it was good business to invest in the economic zone.

“On the other hand, it killed the deal, because in an IPO [if] 70%, 80% or even 90% can be taken by strategic investors, the portion for retail investors is very limited. The intention of the strategic investors is to hold the shares for a long time, to cooperate with the issuers. That is why liquidity is very limited. That is the mechanism of the Cambodian stock market.”

Given limited demand from retail investors and the subsequent lack of liquidity in the stock market, it is risky for securities firms to underwrite IPOs in Cambodia.

Trading in Phnom Penh SEZ shares in 2019 shows the impact strategic investors can have on the liquidity of a stock. Weekly volumes for the zone rarely passed 20,000 shares; at times it was below 5,000 shares. But in late March, 3.05 million shares appeared on the market as a large strategic investor offloaded its entire position.

The stock was mostly picked up by other non-retail buy-and-hold accounts, says Shikata.

Cambodia lacks other institutional investors, such as pension funds, because the country has yet to develop a system of custodian banks, though as many as three banks, including domestic and foreign names, have applied for licences, and international investors want custodians before investing, particularly a frontier market.

“I have had many calls from people in other countries who say they want to make an investment in Cambodia, but when I explain that there is no custodian bank they stop discussing the idea,” says Shikata. “I changed my strategy, so I explain first that there are no custodian banks and then people can decide if they want to keep talking.”

Improvements

Some improvements to the market have been made.

The stock exchange has relaxed restrictions on trading limits and methods, which has helped increase liquidity over the last 18 months, says Shikata. In early 2018, the stock exchange increased the cap on daily stock price rises from 5% to 10%, while introducing a ‘market order’ method for buying shares. Common to other stock markets, the practice enables investors to place orders for however many shares, regardless of the price. Previously the CSX only allowed ‘limit orders’, which must be based on a price.

After a few months of the market digesting the change, it began to lift liquidity, with trading hitting new highs in 2019. The exchange’s index showed strong growth in the third quarter, with market capitalization up more than 40% from the second quarter, CSX data shows.

The index rose to 869.16 points at the end of September, its highest level since the first stock was listed on the CSX in 2012. The stock exchange’s market capitalization reached $800 million – up from $570 million in the second quarter, the data shows.

“These two things made the stock prices jump up,” says Shikata. “Especially for the state-owned companies – the number of Cambodian investors increased and increased.

“They love their state-owned companies. They don’t care about the price, they just want to buy the shares. There is fast momentum, the price has increased a lot.”

As for trading values, Shikata adds: “In 2017, trading was around $10,000 per day, now it is $30,000 to $40,000 per day. Of course compared to other countries it is small, but the market itself has grown. And the number of trading accounts has increased a lot as well.”

We have to dare to introduce something new. We have to dare to do something to develop this market. We can’t bring in one company per year, it is too slow - Hong Sok Hour, CSX

From January to November 2019, each of the CSX’s three SOE stocks traded up. The PPWS climbed 39%, while the stocks of Phnom Penh Autonomous Port and Sihanoukville Autonomous Port jumped 26% and 68% respectively.

The two private listed companies have not enjoyed the same price surge. Garment manufacturer Grand Twins International (Cambodia), which floated in 2014, saw its stock drop 14%, while Phnom Penh SEZ, trading since 2016, fell 10%.

There are signs that the number of international investors, many retail accounts, is growing rapidly. Cambodia’s stock exchange, in contrast to many of its neighbours in the greater Mekong region, is a remarkably open market. Foreign investors can easily set up accounts with locally based securities firms and trade on the bourse.

The majority of offshore investors active on the CSX, and particularly behind the increase in numbers, are South Korean and Japanese, according to multiple sources. Korean and Japanese companies have a history of investing in the region and a presence in Cambodia, which has overflowed to their retail investor base.

The CSX was created as a joint venture between the Cambodian government and the Korea Exchange. It remains a 55%/45% partnership of the two. Along with Korean expertise came KRX’s IT systems for stock and bond trading.

While the exchange was officially launched in 2011, a memorandum of understanding to develop the CSX was signed between Cambodia’s and Korea’s ministries of finance around the year 2000, after Korea approached the Cambodian government.

When chief executive Hong abandoned his PhD and took charge of the stock exchange project at the Cambodian ministry of finance, the ideas of a stock market and bond market were both floated. But it wasn’t until 2018 that the latter was born.

Pipeline

After the debut issue by Hattha in 2018, fellow microfinance institution LOLC (Cambodia) issued a CR80 billion three-year dual-tranche bond in April 2019, which comprised a foreign exchange-indexed tranche paying 8% and a fixed-rated tranche paying a 9% coupon.

ABA Bank became the first commercial bank to print a bond, raising CR128 billion. And following the strong response from retail, as well as institutional investors, ABA is planning a repeat issuance in 2020.

Most of the issuers in the pipeline are expected to be financial institutions. For issuers such as banks, which have their own internal audit processes, corporate bonds can be completed from conception within six months, whereas IPOs can take up to two years.

While the corporate bond market has become an attractive fundraising option, it has also caught the eye of investors, particularly institutions that are looking for somewhere to park capital. For example, international insurance firms Manulife and Prudential each invested $300,000 in ABA’s issuance and both are hungry for more, according to Shikata.

Local government is doing its part in promoting the bond market. One particularly attractive incentive is the reduction on income tax of up to 50%. In the case of debut issuer Hattha, the government also promised to eliminate all existing tax debt if it listed within three years.

Up next is a bond by a Cambodian trading company, primarily involved in automobiles; it will be the first non-financial issuer. The deal is ready to go, according to Shikata, but is just waiting for approval from the SECC (expected as Asiamoney goes to press) and will launch a month after that. Immediately following it is one of Cambodia’s top two microfinance lenders. It plans to print its bond by March 2020.

Both deals have the benefit of a CGIF guarantee.

“Foreign investors don’t care about the risk because of the guarantee,” says Shikata. “To get foreign investors to understand the Cambodian market is also our mission.”

The Cambodian regulator is also looking closer to home, having signed an agreement with the Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand in September to encourage cross-border equity offerings and potential depository receipt (DR) listings.

Thailand has been pushing such agreements with other countries in the region for many years, but has yet to see an international issuer IPO since they were permitted in 2015. As part of the tie-up, the two market regulators are working on implementing cross-border equity deals and the sale of depositary receipts. It will set out guidelines for issuers from either country looking to tap each other’s equity markets.

Ruenvadee Suwanmongkol, SEC Thailand’s secretary general, says the aim was to allow issuers from Cambodia and Thailand to list or sell shares outside their home jurisdictions.

Hong of the CSX, speaking about the potential of cross-border DR listings, says: “We have been discussing this with the stock exchange of Thailand and we have made some progress. If we could get that through, it would be a big boost for the market.”

He adds: “We have to dare to introduce something new. We have to dare to do something to develop this market. We can’t bring in one company per year, it is too slow.

“We can’t wait 100 years for 100 companies.”