The US Treasury set out to sell close to $180 billion of new government bonds in the last week of the first quarter, with notably large auctions of $66 billion of two-year notes on Monday and $67 billion of five-years on Tuesday, plus another $50 billion of supply besides that.

There were plenty of indirect bidders for the two-year, more than on any such issue since last June. Primary dealers weren’t left holding too much of it. And even though the Treasury had to pay a 0.5 basis point new-issue premium, that set a good tone for a busy week.

But then, almost every week is a busy week for the US Treasury, even with the economy performing well, talk of no landing rather than a soft or hard one, and tax receipts set to boost the already healthy balance of $800 billion in the Treasury General Account.

That sounds like a big number. But it shrinks to a rounding error next to total US public debt outstanding. This has reached $34.6 trillion. It is growing by another $1 trillion roughly every 100 days, according to analysts at Bank of America.

The separation of powers in the US, and the difficulty of regularly agreeing new legislation to approve debt limits in a bitterly divided Congress, now frequently raises the prospect of a technical default. It has been like this for years.

Even before Fitch downgraded the US last year, nerves had been periodically jangling. And on Tuesday, Phillip Swagel, director of the independent Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which produces regular forecasts of US fiscal deficits and total debt, as well as cost analysis of all manner of proposed legislation, made the Treasury’s week just a little harder.

He told the Financial Times of his fears for a potential Liz Truss-style crisis if the US does not address its growing deficits and debt burdens.

This was an eye-catching headline for the FT, to which we tip our hats. The CBO is a non-partisan body that does not recommend or opine on policy. Rather, it provides analysis and projections.

In fact, increasing the public debt is one of the few issues in the US that enjoys broad bipartisan support. Deficit hawks are a close to extinct species.

The debt stood at $19.85 trillion when Donald Trump last took office in January 2017. After his generous tax cuts and spending during Covid lockdowns, it had grown by $8.6 trillion and hit $28.43 trillion on that memorable January day when Joe Biden was confirmed in office. Biden has so far added another $6.17 trillion to the debt.

Soaring debt

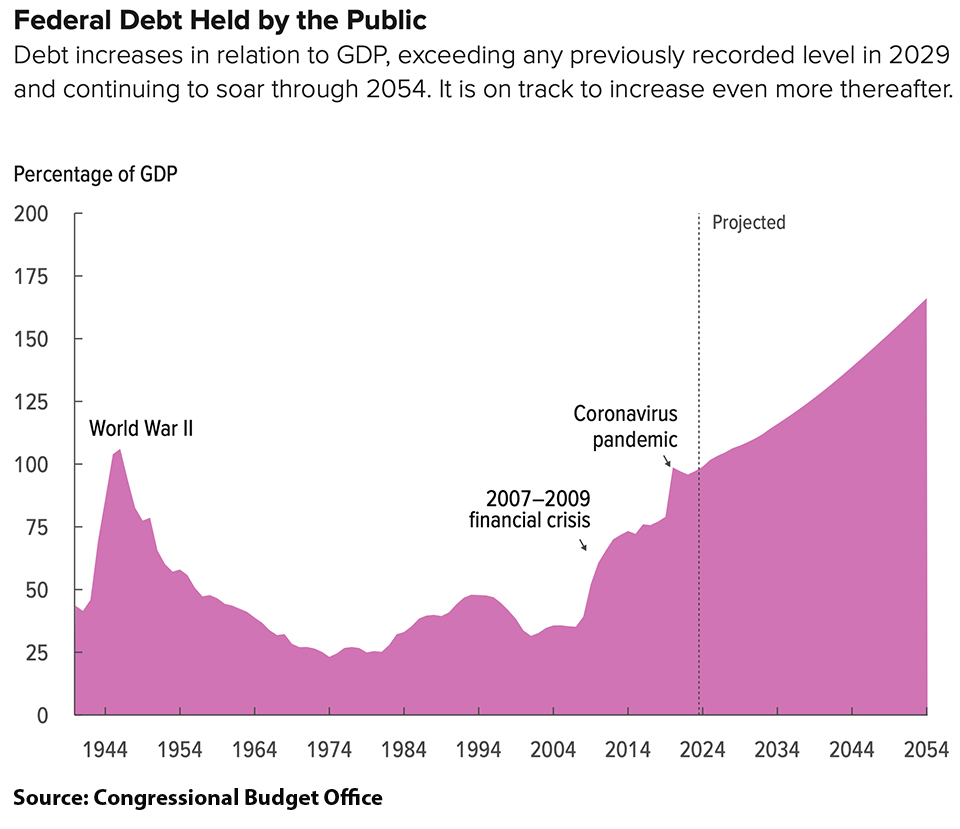

The CBO runs long-term projections based on continuation of prevailing tax laws and spending programmes. Its latest long-term forecast is for the US debt-to-GDP ratio, which hit an all-time high of 105% at the end of World War II, to surpass this peak and hit 107% in 2029, then “continuing to soar” to 166% of GDP by 2054.

Annual fiscal deficits will average 6.7% of GDP over the next 30 years, compared with 2.2% over the last 30 years and just 1.6% over the last 50 years.

Is it time to panic? No. Not yet.

The US Treasury market is not going to go through anything like the doom-loop of forced selling by regulated buyers that beset the UK gilts market in 2022 following then-chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s disastrous fiscal event: at least not any time soon.

The US can no doubt sustain a once-unthinkably high level of public debt to GDP if it decides that is appropriate to the desirable extent of the state’s role in the economy.

This is still the world’s largest and most powerful economy, after all.

The Federal Reserve won’t be able to cut rates at anything like the speed or to the extent bond markets were confidently predicting at the start of this year. The Fed is caught

For all the despairing or wishful talk of the dollar losing its reserve-currency status, no other candidate – not the euro, most certainly not the renminbi – comes anywhere close. That status confers an exorbitant privilege on the US. It will not have to pay the high cost of servicing its fast-swelling public debt that any other country would have to pay and at the first sign of which Truss and Kwarteng were swiftly defenestrated.

But it may well be time to worry.

When the annual US deficit recently peaked at 14.7% of GDP in 2020, interest outlays contributed a cost equivalent to just 1.6% of GDP. But higher rates on a bigger debt are set to increase the expense of servicing these ever-rising debts. In 2023, the total deficit had more than halved to 6.2% of GDP. But interest expense on the debt was suddenly accounting for 2.4%.

The CBO expects debt-service costs to soon exceed the US primary deficit, with the primary deficit at a respectable looking 2.8% in 2025 but net interest outlays adding another 3.3% and so boosting the total deficit up to 6.1%.

Sovereign debt dynamics can be tricky. Economics 101 teaches that an expansion of supply reduces price. So, in theory when an economy contracts and state spending increases, bond yields should go up. Of course, they actually go down. That is because central banks tend to be cutting policy rates even as debt management offices pump out supply.

Debasement trade

But that contrary move in falling yields and rising supply only holds as long as citizens and overseas investors retain faith in the currency. Expanding public debt is inherently inflationary. Debasement trades are in play right now, most obviously Bitcoin returning to $70,000 and gold up at $2,175.

The Federal Reserve won’t be able to cut rates at anything like the speed or to the extent bond markets were confidently predicting at the start of this year.

The Fed is caught.

Rates repression was the great conjuring trick of the last 15 years. If you can’t reduce the large size of your debts – and governments don’t repay them, only perpetually refinance them – quantitative easing was the way to reduce the cost of servicing them.

There will be a point below which the Fed cannot hold market rates. The Bank of Japan has just hiked, raising the possibility of at least some modest repatriation of Japanese investment in dollar assets, notably US Treasuries.

But on the day the BoJ abandoned yield-curve control and raised rates into positive territory, it also confirmed that it would continue to buy Japanese government bonds at the same pace as before.

Since the Fed began quantitative tightening, it has reduced its bond holdings by $1.5 trillion. But on March 20, chair Jerome Powell confirmed that the Federal Open Market Committee believes it will be appropriate “to slow the pace of runoff fairly soon” and that doing so would “reduce the possibility that money markets experience stress”.

The Fed, unlike the Bank of England in the brief tenure of Truss and Kwarteng, should not have to embark on emergency purchases of Treasury bonds. But quantitative easing will never be fully reversed. Excessive debts, persistent inflation, high rates and fear and loathing at monetary financing will continue to bedevil financial markets and keep investors in a perpetual state of intolerable uncertainty.

That is what makes it all such fun.