Korea’s banks are caught in a curious paradox. Despite an unparalleled onslaught from regulators and intense profitability challenges during the past 14 months, the Korea KRX Banks Index, which tracks major publicly-listed commercial banks, surged 19% in the first quarter of 2024 – its best performance since the second quarter of 2017.

The sector’s troubles began in February 2022 when president Yoon Suk Yeol criticized Korean banks, labelling them an oligopoly causing significant public “suffering” through high interest rates. His remarks highlighted the stark contrast between banks’ generous employee bonuses and struggling microbusinesses facing high borrowing costs.

This statement unleashed a triple strike on the industry.

First, in response to the president’s stance, the Financial Services Commission (FSC), the country’s financial watchdog, mandated greater transparency on loan-deposit rate differences, prompting many banks to lower rates.

This regulatory strong-arming is not unique to Korea. China’s National People’s Congress published similar suggestions last year, urging the financial sector to prioritize the real economy over their bottom lines. Chinese banks have even donned the mantle of ‘white knights’, heroically providing critical lifelines to cash-strapped property developers caught in a real-estate crisis.

Despite shrinking profit margins and mounting high-risk assets, China’s top four banks also experienced substantial stock-price rallies in 2023.

New players

Korea’s banks face additional challengers – the second strike in the triple threat. Following the head of state’s explicit opposition to a handful of banks reaping massive earnings, the FSC opened the door to new nationwide players for the first time in 30 years.

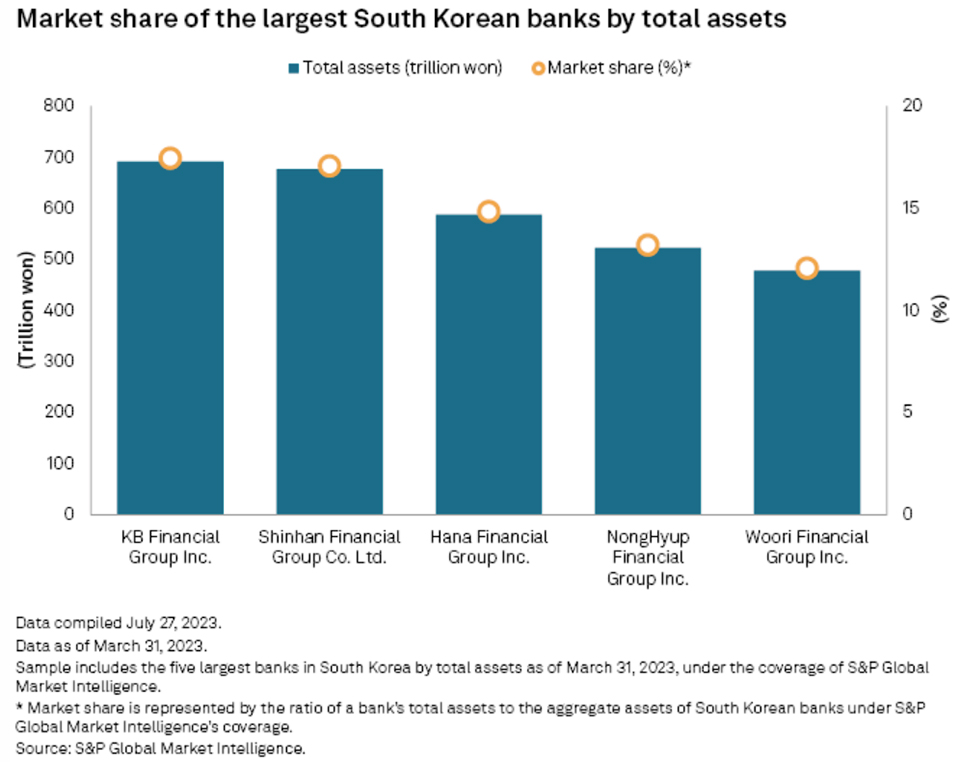

This policy targets the concentration of power in the banking sector, where the five largest banks dominate, holding 74.6% of the sector’s total assets, according to a 2023 S&P report. The FSC aims to foster competition, curb easy profits and push banks to become global players “for the country’s economic standing”, as stated by FSC chairman Kim Joo-hyun.

The threat of new entrants, however, may be limited. Rapidly growing digital banks, such as KakaoBank, appear content as pure-online players for now, while most regional traditional banks are reluctant to invest in branches amid the economic downturn.

Indeed, so far only Daegu Bank has applied to convert its regional licence into a national commercial bank licence.

The third strike comes from regulators’ concern over a systemic financial crisis, with household debt considered a ticking timebomb that could damage the Korean economy “several dozen times more than it did during the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis”, according to Korea’s former presidential chief of staff Kim Dae-ki.

Authorities have, therefore, tightened access to 50-year mortgage loans as Korea’s household debt hit a record W1,100.3 trillion ($836.1 billion) in February, marking the 11th straight month of growth. The household debt-to-GDP ratio also climbed steeply from 92% to 108.1% between 2017-2022 – the fastest growth among OECD nations.

Profit at what cost?

A regulatory overhaul may be long overdue.

A headache for banks is their unrestrained sales of equity-linked securities (ELS) linked to the HSCEI, an index that tracks the largest Chinese corporates listed in Hong Kong.

Despite the low liquidity and niche nature of this index, Korean banks have sold 82% of the total W19.3 trillion of these high-risk products, primarily to retail consumers. Kookmin Bank accounted for more than half of bank sales, while Shinhan Bank, NongHyup Bank, and KEB Hana Bank each accounted for 13% to 16%, and Standard Chartered Bank Korea accounted for approximately 8%, according to Fitch Ratings.

The recent stock rally in Korean banking could mark the beginning of a longer-term recovery

Most ELS were sold in early 2021 when the index peaked. Since then, it has halved, causing a loss rate of around 50%.

CreditSights estimated W5.8 trillion in investor losses as of February 2024. Regulators have confirmed mis-selling and mandated banks to compensate investors for 20% to 60% of losses, further denting profits.

Banks’ overseas real-estate funds tell a similar story. Authorities disclosed that, as of end-2023, the top five banks face potential losses of W753.1 billion on these funds amid a global commercial real-estate downturn. Although maturity extensions may defer losses, this remains a looming risk.

Hope of reform

The silver lining for the sector is that these risks have already been priced in.

The key driver of the stock rally is the government’s corporate value-up programme, inspired by Japan’s successful stock-market reforms. The programme aims to align investor aspirations and corporate motivations, encouraging corporates to understand and meet investors’ expectations.

This poses uncertainty for the banking sector, but investors can take comfort in the fact that the FSC aims to emulate Japan’s success in addressing the ‘Korea discount’. The regulator will leverage the banking sector to showcase this process.

The government’s prioritization of this initiative is evident in the busy schedule of FSC vice-chairman Kim So-young, who met with foreign investors in Singapore and Thailand in March.

The FSC will provide detailed guidelines in May and launch a dedicated web portal for companies to disclose their value-up programmes in the second half of 2024.

Dividend payouts

In addition to long-term structural improvement, one quick fix to ‘value up’ is to increase dividends, as seen in Japan. With price-to-book ratios ranging from 0.3x to 0.5x for leading Korean banks, there could be upside. A new dividend policy, effective from March, pressures firms to boost payouts and increases the transparency of dividend payment, allowing investors to know the payout before buying or selling shares.

Don’t underestimate the importance of dividend payouts in banking-sector valuation. The Chinese banking sector’s rally, despite poor fundamentals, has demonstrated the success of similar measures, with regulators vowing to investigate corporates not paying appropriate dividends.

The recent stock rally in Korean banking could mark the beginning of a longer-term recovery. Regulators seem resolute in their efforts to boost corporate value, and Japan has provided a detailed workbook for success. While the dominance of large banks is likely to persist, they will probably operate with updated compliance and risk-control standards, making the sector a more attractive one for investment.