Paul Lynam is busy. The chief executive of Secure Trust Bank, one of the army of smaller UK banks commonly lumped together as ‘challengers’, has recently emerged from a first-half results season that went well after record profits. He is also preparing a move from London’s junior stock exchange, the Alternative Investment Market (AIM), to a full listing on the main board in the fourth quarter. And he is planning to launch a new mortgage offering.

That is enough to keep anyone busy, but right now he also has bigger things on his mind. Solihull, the West Midlands town where the bank has its headquarters, feels a long way from the City of London on a damp September Monday. But Secure Trust Bank and Lynam are among the players in a regulatory tussle spanning Threadneedle Street, the dreaded European institutions in Brussels and the technocrats of Basel.

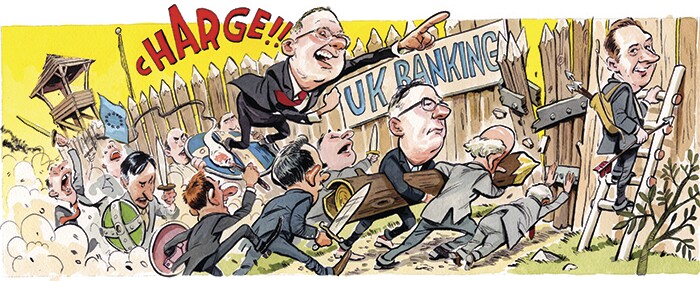

Challenger banks feel hard done by, beaten down by a regulatory capital regime that they say unduly favours the long-established big banks and penalizes those with more moderate scale or ones that are newcomers to the business. That story starts with Basel, but it is the European Union that lands the heaviest blow for UK banks by insisting that member states implement Basel standards in full on all banks, whatever their size.

The result, say some of the challengers, is that they can find themselves having to set aside up to 10 times as much capital as a big bank would do for an identical risk. Regulators dispute the scale of that disparity, but they do agree that a disparity exists. Unhelpfully, the gap appears to rise as the risk drops. That in turn pushes the challengers into higher-risk business to generate returns and leads many to complain that they are condemned to compete with each other rather than stand a chance of taking business from the big names.

Lynam, as chairman of the challenger banks panel at the British Bankers’ Association (BBA), has been at the forefront of the campaign for change. His plans to move into mortgages later this year also give him a clear commercial interest in banging the drum. He has wearily run through the arguments many times with counterparts at other banks, with the Bank of England and with the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA), the regulator that effectively governs this issue in the UK.

“The real cause of the lack of effective competition in UK banking is the extreme capital discrimination against challenger banks and small building societies,” Lynam says. “The hard facts are that the five biggest banks and Nationwide control 80% of the UK mortgage market. They know that the smaller banks and building societies have a finite ability to lend relative to them because of the capital disparity. And the smaller banks also have a finite demand for deposit funding.”

Euromoney’s conversations with other challenger bank CEOs reflect similar concerns. But their needs and priorities often differ. Some, like Atom Bank, which claims to be the first UK bank “built exclusively for mobile”, only opened for business this year. Others, like Secure Trust, another branchless bank but one that has been around since 1954, look rather different. A broad church they may be, but they do not all sing from the same hymn sheet.

The roots

How did we get here? The roots of the issue lie in the Basel II standards, first published in 2004 and later developed by Basel III, with risk-based capital allocation at the heart of the new regime. It brought in standardized risk weights for different categories of exposure on the one hand – the ‘standardized approach’ (SA) – alongside a dispensation to use an internal ratings-based (IRB) approach for those banks able to satisfy their local regulators that their models were sufficiently robustly designed and monitored. Big banks that were able to design complex models and make use of vast internal datasets duly did so.

In the EU, Basel standards are now implemented through the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) and the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). Almost always, member states must hold all the firms they regulate to those rules.

“The key regulatory issue that challenger banks face is the fact that the EU regime on capital and liquidity requirements has been very much developed in light of the post-crisis approach to large international banks,” says Robert Finney, a partner at law firm Holman Fenwick Willan, who has advised challenger banks. “It doesn’t really take account of the smaller, domestic-focused banks.”

Simply put, the complaint goes like this. A large UK bank can do 10 times more low loan-to-value (LTV) mortgage lending than a small bank or building society, despite taking exactly the same credit risk. Under Basel, residential mortgages with an LTV of less than 80% are weighted at 35%. The average risk weight for such mortgages at big banks using IRB, by contrast, works out at about 3.3%. Under the Basel Committee’s final revisions to Basel III, however, the disparity will likely be reduced by the introduction of capital floors for mortgage and corporate risk. This is a fundamental move away from risk-based modelling and towards a standardised approach, and as such has been dubbed Basel IV by the industry.

As things currently stand, however, there is still an eye-catching difference between the two approaches. And the size of the gulf has a competitive effect.

“Everyone is focused on return on equity, so if you are using one third of the capital of a challenger bank, then effectively you can afford to price at a 50% discount and still produce a higher ROE on the same asset,” says Steve Pateman, CEO of Shawbrook Bank, another branchless bank, focused on SMEs and individuals.

The standardized approach therefore comes in for a lot of criticism, but it is worth remembering that it serves an essential role for banks that are just starting out and are unable to implement IRB as they have no history of lending through which to assess performance.

Lynam looks to the US for inspiration, not for the precise detail but for a better implementation of the principle of proportionality.

“The US had arguably a much deeper crisis than the UK, but bounced back much more strongly,” he says. “It has 7,500 banks and some go bust every day without causing a crisis. Only the biggest are regulated in a manner that in any way resembles Basel – the others are managed on a much more proportionate basis by their local Fed.”

I have the image that somewhere there are people sitting in a room pointing at each other

He wants that kind of distinction to be made more explicit in the UK banking sector. “The origins of the Basel rules are relatively sound – to have internationally active and systemic banks operating on a level playing field. But it simply doesn’t make sense to have Furness Building Society subject to pretty much the same regime as HSBC, which is in over 100 countries,” explains Lynam.

If the existing regime was tough, the real kicker for any firm using Basel’s standardized approach came in December 2015, with the unveiling of a new Basel consultation paper on risk weights, expected to be implemented from 2019. Among the proposals, some buy-to-let loans that currently attract a risk-weight of 35% would be stepped up to 70% for LTVs of below 60% and 90% for those with LTVs of 60% to 80%. Loans to house builders might be weighted at up to 150%.

At fault is a system that fails to take into account the different maturity profiles of different markets, critics argue.

“There are countries where lending to house builders carries substantial risks, but you don’t see many ghost towns lying empty in the UK,” notes Lynam. “Every sensibly priced new build is snapped up by eager buyers.”

“What’s proposed is going to be a lot more penal,” says David Wong, a partner in PricewaterhouseCoopers’ financial services risk and regulation practice, where he heads credit risk. “What is concerning the challenger bank community is the increase in risk weights. The status quo is already bad, but what’s coming looks a lot worse.”

It is particularly bad for those engaged in the area of buy-to-let (BTL) mortgages, for example, a sector that is already under regulatory pressure in the UK through higher stamp duty costs and the impending withdrawal of crucial tax breaks such as the ability of landlords to offset the financing costs of their mortgages.

In its response to Basel’s consultation paper on the changes, the BBA wrote: “We do not agree with the Committee’s view that BTL lending is substantially riskier than the financing of owner-occupied residential property, in our view the risks are not dissimilar at Loan-to-Value ratios below 80%.”

It also took aim at the proposed weightings for house builder exposure: “A more refined slotting approach would facilitate a proportionate risk-based approach, one which could be adapted to ratchet down risk weighting as [a project] moves towards completion.”

What is being called for is the ability to recognize different countries’ market characteristics, and the BBA’s comments were echoed in the responses of many UK smaller banks.

For as long as the UK was governed by European regulations, change could only come at the Basel level. So even if not completely hopeless, the situation certainly looked grim for any bank using the standardized approach.

Then came Brexit.

Rules changed

It is June 30 2016, just seven days after the UK’s referendum vote to leave the EU, when a letter lands in the inbox of Andrew Tyrie, chairman of the Treasury Select Committee. The CEO signatories are Phillip Monks of Aldermore, Graeme Hartop of Hampden and Co, Andy Golding of OneSavings Bank, Pateman at Shawbrook, Ian Lonergan of Charter Savings Bank, Craig Donaldson of Metro Bank and, of course, Lynam at Secure Trust Bank.

The letter sets out in plain language the by-now familiar complaints of the challenger banks: the lack of a level playing field when it comes to capital and the funding advantages of the big banks. But more intriguingly, it outlines how the Brexit referendum result has changed the rules of the game – and, as the challengers see it, the potential solutions to their problems.

“The EU referendum result, once implemented, means HM Government and the Bank of England will have the discretion to determine which aspects of legislation derived from the EU they wish to be maintained in the UK and which they wish to reform,” the chief executives write. “We hope that will result in a more proportionate approach to the regulation of smaller banks, particularly in respect of capital.”

If the result of Brexit negotiations is that the UK remains committed to EU rules on the implementation of Basel – perhaps as a quid pro quo for maintaining some or all passporting rights for the internationally active institutions – then all bets are off. But if that does not happen, then in theory there is nothing to stop the UK going its own way.

Could that happen? As with much of this debate, the answer is yes and no: it is possible in some ways, but not likely in others. The Bank of England and the PRA would not comment on the record for this article, but they have not made any secret of their broad sympathy for smaller banks’ predicament in the past. And in their more optimistic moments, challenger bank CEOs and their advisers certainly draw comfort from the language used by the key regulatory players.

Challenger banks have long argued for better treatment, but last year saw an increase in activity. In September a band of them lobbied the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer on a number of issues, including capital requirements. The Treasury Committee was quick to take up their case with Andrew Bailey, who was head of the Prudential Regulation Authority.

In November 2015, Bailey wrote to Harriet Baldwin, at the time economic secretary to the Treasury, setting out the PRA’s approach to a European Commission consultation process on revisions to the CRD and the CRR. He dwelled on the fact that the Bank of England’s response focused on the case for greater proportionality: “The Bank’s view is that policymakers need to weigh the desirability of a single rule book for all firms with wider objectives, including growth, financial stability and effective competition.”

But just as important were his comments on the concept of proportionality in the IRB regime – what those in the challenger bank community like to call an ‘IRB-lite’ approach, and one that many are pinning their hopes on: “We will consider whether our approach to the internal credit model application process could be made more proportionate for smaller banks and building societies,” Bailey wrote. Baldwin’s response made it clear she liked the sound of that.

Most importantly of all, the letter made clear that Bailey considered the one-size-fits-all approach to be a function of the EU’s implementation of Basel, rather than of the Basel standards themselves. That thinking, if it persists now that Bailey has moved on, could define how UK regulators approach a post-Brexit world. If anything, it makes it less likely that the PRA would consider going its own way, if it considered that Basel had the potential, over time, to introduce more proportionality.

In February 2016 Treasury Select Committee chairman Tyrie wrote to Bailey asking for examples of the average capital requirements of incumbent banks compared with new entrants. In his reply, Bailey explained that averages were difficult to produce, but also that while there was certainly a difference in requirements, that difference was often not as large as was sometimes suggested.

Firms using the IRB approach were required to have more sophisticated risk-management capabilities, which carry their own cost, he noted. And they were subject to the limiting factor of the leverage ratio, which is set at 3%. Ultimately, he said, IRB firms that had very diversified business models were at an advantage, but not as much as was claimed when just comparing risk weights.

Other regulatory sources that Euromoney has spoken to agree with that assessment, noting that a large firm might have all sorts of much higher weight exposures like corporate lending or equity, which have an offsetting effect. If a firm is leverage-ratio-constrained rather than risk-weight-constrained, then an individual asset may have a considerably lower risk-weight within the IRB methodology than at a firm using the standardized approach. But the big bank as a whole is subject to the leverage ratio across its entire balance sheet, as well as a host of other measures.

Yes, capital plays an important role, but commercially if you are trying to be a mortgage lender and you simply have the same products as existing players have, then what’s the point? Just trying to do a rate play won’t be the answer

Bailey has since been succeeded by Sam Woods, who was an important behind-the-scenes contributor to the Vickers Commission inquiry into the UK banking sector in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. He made his first appearance before the Treasury Committee in July 2016. Conservative Member of Parliament Chris Philp led the charge on the challenger bank topic on behalf of the committee, wanting to know if Woods considered the risk-weighting disparity to be fair to challenger banks. Woods stuck to the regulator’s long-standing line, cautioning against accepting the most dramatic claims at face value.

“Some of the ways in which those gaps are portrayed are an overly crude reading of what is going on,” he told the committee. “But that is not code for: ‘I don’t think there is an issue’. There is an issue. I just think that the ‘10 times’ claims and all that stuff is overblown.”

Lynam remains unconvinced by the argument. “I’ve had this conversation with Andrew [Bailey] face to face,” he says. “The fact is that the leverage ratio only has an impact on Nationwide because it’s a monoline. The others are able to ensure that they have the optimal composition of their balance sheet to maximize the benefits of IRB. There is no way you can argue that the others are leverage ratio-constrained.

“And yes, there are buffers, but the reality is that they are based on the risk weights, so the buffer being a percentage of a very low number is itself a very low number.”

In his comments to the Treasury Committee, Woods steered clear of where the capital disparity appears at first glance to be greatest – a low LTV residential mortgage extended by a challenger bank versus one lent by a big diversified firm – and instead considered a monoline lending in the 70% to 80% LTV bracket, where he said the average risk weight comes out at just under 13%, still well below the 35% standardized approach. “I am a bit troubled by that difference,” he said.

Woods told the committee that the regulator’s approach was to be guided by Basel, but that he was also acutely aware of the dangers of a one-size-fits-all approach: “It is very important that we try to get to a more risk-sensitive standardized formula,” he said. “The reason for that is partly the competition reason but it is also safety and standards – it is rational if you are constrained in that way to go into high-risk mortgages.”

That view is certainly in keeping with earlier statements by Bailey that the UK’s preferred approach was to work with Basel standard-setters to arrive at a system that allows more proportionality in the treatment of institutions. But he also notes that the IRB method is an alternative and one that is not closed off to smaller firms. Provided that models are well built, then, he says, there is in principle no bar to small firms using them.

There may be no bar in principle, but there can be in practice – a lack of data. As Philp reminded Woods, many firms do not have sufficient through-the-cycle data to meet the requirements to be able to satisfy regulators: “They say they want to do it, but they can’t.”

Some can, however, and with the prospect of an even tougher Basel standardized approach, are increasingly choosing that option. But in doing so they are committing to an immense amount of work; and there are other developments that may erode some of the advantages of the IRB route.

Fraught process

It can take years to make the switch to IRB methodology – if everything goes well. It is a fraught process, even for big banks with the resources to devote considerable manpower and systems to the task. Despite the challenges, Paragon, Aldermore and Clydesdale Bank are among those working towards that goal right now. Clydesdale said in its most recent results announcement in September that it was planning to move to IRB by the end of 2020, giving an indication of how long such a process can take.

For many other small firms, it is not an option; they would always struggle to collect and analyze sufficient data, or build and maintain the kind of models that will keep regulators happy.

There is no catch-all requirement of precisely how much data is required, but what is certain is that regulators need to be satisfied that the data a bank has available is illustrative of portfolio performance through an entire credit cycle in the relevant asset class. For some more predictable and homogenous asset classes such as segments of the mortgage market, that might be three years of data as a starting point; for others it might be seven.

Presenting its full year results for 2015 in March 2016, Aldermore told the market that it intended to pursue an IRB approach. It was also in March, however, that the Basel Committee released its consultative document on the use of the IRB approach and its plans to address the excessive variability in the capital requirements for credit risk that it generates by imposing capital floors.

At buy-to-let specialist Paragon, teams have been working on an IRB transition for roughly the last five months. Euromoney catches up with CEO Nigel Terrington in his London satellite office – although he spends most of his time across the road from Lynam in Solihull, apparently the hub of UK challenger banking.

Data is not the problem for Terrington. He reckons he has better data on his segment of the market than pretty much any other firm going. Decades of statistics can show him the precise credit performance of a range of specific LTV buckets of specific vintages, for example. (Euromoney is startled to hear that Paragon has written 25,000 loans since 2010, but that at any time only one has been past 90 days due.)

Once the data is in place, the next step is to build the models to evaluate measures such as probability of default, loss-given default and exposure at default. Terrington does not dismiss the complexity of this, but he still describes it as “the easy part” compared with the business of demonstrating their effectiveness to regulators.

“The key thing regulators are interested in is the use test,” he says. “They want to see how your models are used, how they are applied to your data, how you analyze risk, how you price your products based on that and how you manage your resources and governance.”

Regulators will generally want to see the models working for at least a year, and they need to be sure that senior management have sufficient understanding of them – hiring a bunch of whizz kids to build a black box is not an option. Then comes further auditing and interrogation.

“The data is only part of the equation,” adds Nihar Mehta, who heads the banking startups team at PricewaterhouseCoopers. “The other part is the use of the model and the understanding of it. Do you have the skill set collectively at the board level?” Only after all this do you get to actually apply for IRB.

“It’s a lot of work,” says another adviser, “and the PRA had tended post-crisis to be resource-constrained. It was a case of: ‘You apply, and we’ll tell you if you are good enough’. Then they might reject you. What they don’t want is to act as some kind of free consultancy.” This is changing, however, and most that Euromoney spoke to said that the regulator was now far more engaged before application.

The data difficulty, highlighted by Philp, has given rise to suggestions by challenger banks about how UK regulators might ease the path. Chief among these is the concept of making datasets available to banks that lack them. Banks report reams of data to the Bank of England and, so the theory goes, this data might be anonymized and pooled into generic sets for other banks to use. Unfortunately for the challengers, there has been nothing to suggest that the Bank or regulators see this as their role.

In any case, banks are already permitted to use external data if they wish to do so – firms like Equifax, a US-based consumer credit reporting agency, can supply datasets for this purpose. But that still leaves the challenge of a bank proving that its portfolio is sufficiently comparable to a generic dataset for that dataset to be a valid input into a model. For many that is impossible to prove unless the bank has its own data over the cycle.

There are areas where it might look like it could be achieved – specific sub-segments of mortgage lending, for example. A bank could create a dataset going back decades of 50% LTV mortgages for borrowers in a certain income range with certain levels of seasoning and across different vintages. But even this would fail to capture the different underwriting methods and standards of different firms.

Could there be other approaches? Phillip Monks, CEO of Aldermore, notes that the Bank of England currently satisfies itself of the performance of a bank’s assets when accepting collateral for its term-funding scheme, a mechanism that provides funding to banks at close to bank rate. He thinks that at least has the potential to offer some assistance.

“A number of us pledge mortgage assets through the Bank of England’s funding schemes, and in order to accept that collateral the Bank goes through a credit analysis process, comparing our assets to its benchmark data from the industry,” he says. “So it knows the quality of those assets and how comparable they are to the industry data as a whole. We have pledged about £1 billion of assets from our mortgage book, out of a total of about £1.5 billion residential and £2.7 billion buy-to-let, so the amount is statistically meaningful.”

Transitioning

Much of this is tinkering around the edges, however. Regulators have huge scope to make their judgement on whether or not IRB is appropriate for a firm, even if the procedures were made simpler or more tools made available.

“The reality is that, whatever changes are proposed or are made, it would be easy for the PRA to find a reason why most firms don’t meet the letter of IRB standards if it really wanted to – there is plenty for it to hang its hat on,” says Steven Hall, a former theoretical physicist, who now works at KPMG in what might be an even more difficult field – helping challenger banks transition to IRB.

Hall argues that the PRA is more interested in whether or not a firm shows that it can act like an IRB bank: “Does it have the right governance? Does it really get it?”

It all comes back to Basel, however. The changes that Basel IV could herald are expected to add 10% to the capital requirements of the big banks and take away a significant amount of the risk-sensitivity that the IRB approach has previously enjoyed. Banks making the leap to IRB may wish they had not.

In terms of transitioning, however, there is another regulatory move under way – this time in the accounting field – that could help encourage more banks to switch to IRB at the earliest opportunity, even if they are small.

IFRS 9 is an international accounting standard that will be implemented from 2018, and much of the work involved in preparing for it sees substantial duplication with the concepts in IRB. It will force firms to make impairment provisions for assets based on their expected losses over the 12 months after acquisition. If the credit risk of an asset increases substantially, then the firm must provision for its expected lifetime losses. Doing all that involves building models.

“There is a reasonable amount of overlap as firms need to model default rates, loss rates and exposure values,” says KPMG’s Hall. “Most that have IRB are leveraging it for IFRS 9. You could envisage firms using IFRS 9 to get a first generation of models, to show the PRA that they have a model culture, before then improving this under version two or three for IRB purposes.”

Monks at Aldermore is one who is working with the two processes in parallel.

Those with knowledge of the application process for IRB note that before any talk of IFRS 9, there were numerous banks that investigated moving to IRB, only to decide against it. Cynics say that this might have been because such firms discovered that they were in fact better off on the standardized approach, particularly once the cost of transitioning to and maintaining IRB was factored in.

I don’t think much will change in the long run – I don’t see much appetite to create a more relaxed environment

However, the expectation now is that the twin encouragements of a tougher standardized approach and the requirements of IFRS 9 will push many more mid-tier firms into the arms of IRB.

“The economics of IRB have changed now,” says one observer.

The PRA is steeling itself for this – and looking to help where it can. Earlier this year it conducted what advisers refer approvingly to as “outreach”, asking the industry if there were barriers to firms who wanted to move to the IRB approach. The conclusion, unsurprisingly, was that the understanding of the requirements of the move and the best way to meet them was patchy.

As a result, the regulator announced in its first ever competition report, published at the end of June, that it would look to set out more clearly how to make the switch. The guidance is expected to be revealed later this year. It will give firms a roadmap of how to get from A to B – but B will still be the same place. There is no question of the standards that firms have to meet being reduced.

Sense of perspective

There are as many opinions on the debate as there are people involved in it, but Shawbrook’s Pateman is one of the more forthright on the need to keep a sense of perspective. He meets Euromoney in his office on London’s Bishopsgate the day before he is due to embark on a packed schedule of investor meetings in Edinburgh, the US and Canada.

He broadly supports the push for change, but cautions against using the US as a yardstick: “The US has its own interpretation of Basel; it never adopted Basel III, and arguably didn’t really adopt Basel II either.”

He notes that much of the reason why this is possible is down to a fundamental difference in the role of banks and the resulting impact on balance sheets. In the UK, he says, the banking system exists primarily to provide mortgage lending. Some is securitized, but not to the same extent as in the US; there is no equivalent to Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, the US government-sponsored entities that buy conforming US mortgage debt and repackage it to be sold to bond investors, guaranteeing repayment of principal and interest.

It is not that the US regulatory environment is light touch, it is just solving for a different problem, says Pateman. With mortgages generally not sitting on bank balance sheets, the question of their risk weights is largely irrelevant. The biggest US banks are still subject to tough scrutiny and their leverage ratio requirements are higher – 4% for all firms and at least 5% for the biggest.

Others argue that deviation from Basel might not be desirable, even once it is possible. “I challenge the basic premise on which much of the commentary is based,” says Mark Mullen, CEO of Atom Bank. “If you disagree with the Basel standards as they relate to new banks, then you have a case for saying that local regulators should be able to use a different set of rules. But if you don’t disagree with that, then it is helpful for standards to have as much global currency as possible. I want to be recognized as a proper bank – I don’t want to have special treatment.”

He does not argue against the fundamental problem that Lynam spends his time on: “The issue for us is that because of the rules as they stand, you have the biggest banks sitting on the lowest risk assets. That is actually reinforcing concentration risk in the market.”

But, as with Lynam, it is not stopping him pushing ahead with his plans.

“We are about to launch a mortgage proposition,” Mullen adds. “Pooled data would be very useful to us and others, allowing the use of IRB or a version of it. None of the incumbents are in any hurry to yield their position, though, so that kind of solution is never going to come from the banking industry. The only place it can come from is the PRA.”

But he is also wary of placing too much importance on a UK-specific solution, or one where a more favourable environment can only be enjoyed by firms that restrict their scope.

“The scope of my ambition is not simply UK domestic,” he says. That said, if needs be, he would take the UK domestic business under a more favourable environment rather than be subject to tougher rules in order to access passporting rights.

[Regulators] are listening – it definitely goes a little further than: ‘Isn’t it dreadful?’

It is tempting to think sometimes that much of the talk is a solution in search of a problem. Pateman does not go that far, but nor does he set much store by tinkering with risk weights as a cure-all. “You have to look at what you are trying to solve for,” he says. “I would ask myself: ‘Is the UK mortgage market fundamentally uncompetitive? Does the consumer lose out?’ The answer must be no. You would be hard pushed to find a market that was more competitively priced for consumers.

“But if you simply want to make it easier to be a new bank doing the same stuff that others are already doing, then fine, this would be one way to do it.”

Unsurprisingly, Pateman does not think that should be the priority: “What you should be doing is encouraging people to step into the gaps that other players are withdrawing from, so that’s the higher LTV, less standard credit profile borrowers, or areas of SME lending.

“You shouldn’t have a situation where there are lots of people offering a standard product and then there’s not much on offer between that end of the spectrum and the payday lenders on the other. Making the capital arbitrage play easier is not tackling the problem of those that are underserved by banking at the moment.”

Mehta at PwC agrees: “Yes, capital plays an important role, but commercially if you are trying to be a mortgage lender and you simply have the same products as existing players have, then what’s the point? Just trying to do a rate play won’t be the answer. If you did make data available to newcomers to help them, then there would be some business models that could take advantage of it, but the truly successful ones will be banks that are taking advantage of systemic displacements and trying to serve those parts of the market that are underserved as big banks stop certain activity, where perfectly comparable data may not exist.”

Some pin their hopes on the fact that competition forms part of the PRA’s remit. It does, but not for its own sake. The PRA’s first responsibility is to ensure the safety and soundness of the UK banking system. Its secondary objective is to ensure that competition is not harmed – officials there like to talk of viewing the first through the prism of the second. It is a nuance, but one that takes the regulator away from a responsibility to actively foster competition.

In their quieter moments, many of the challengers ought to recognize the limitations of their regulator and welcome its engagement. There are, after all, some reasons to be hopeful, in spite of the frustrations.

“I think all the constituent bodies have a common view that something needs to be done,” says Monks at Aldermore. “That is a good place to be. This is the first time that we have found ourselves in that position, but that’s also why I am frustrated that we are not getting more traction. I have the image that somewhere there are people sitting in a room pointing at each other.”

Mullen at Atom also thinks regulators are taking note of concerns: “They are listening – it definitely goes a little further than: ‘Isn’t it dreadful?’”

It is also worth noting that there are attempts to build proportionality into Basel standards, at least for those markets that can demonstrate sufficient maturity and track record. It is for this reason, for example, that UK buy-to-let mortgages can be risk-weighted at the standard residential mortgage level of 35%, rather than the higher levels dictated by Basel. It is also why the UK is able to exclude credit unions from the requirements, on the basis that their activity is so exclusively local.

Brexit, while it may have caused a wobble, also did not deter those who want to set up new banks in the UK, in spite of the prevailing regulatory regime.

“On June 24, we called up all our clients that we are working with on new banking registrations,” says Mehta at PwC. “All but one of the 12 said that they would carry on as before. Why? Generally because the models they are pursuing are sustainable in the UK.”

And domestic regulation could yet play into challengers’ hands. The PRA is consulting on changes to the rules for buy-to-let lending that could see banks forced to consider a landlord’s entire portfolio as a business when evaluating those borrowers who own more than three properties. The result of that is being keenly watched by challengers. Many expect big lenders to scale back activity in the sector as a result – a good example of where they could step in as the biggest retrench.

It also remains to be seen what will result from a regulatory review of the UK’s payments systems, which could result in more opportunities for challengers.

Consensus difficult

So what will happen? “If there were an easy answer, we would have solved this by now,” sighs an official who has been scrutinizing the topic for some time. What is clear is that UK regulators will in theory have more flexibility to create an alternative regime, or at least a tweaked version of the current regime, once the country has exited the European Union.

Departure from the EU is now a given; but departure from global banking standards is not and would be a big call by an administration still dealing with the after-effects of a banking crisis. But the PRA has clearly indicated that the possibility of adjusting some regulatory levers or at least clarifying certain processes remains open – as long as it does not result in a weakening of standards.

The variety of different ambitions, scope and business models of the challenger banks makes consensus difficult to establish. But Euromoney’s assessment from its discussions with CEOs is the following.

Talk of smaller banks being able to use average risk weights based on the outputs of the big banks’ IRB approaches is probably pie in the sky. Such a move would likely be impossible before Brexit, and would remain politically controversial and logistically difficult after it.

Equally, data-sharing to make it easier for smaller firms to adopt IRB is also unlikely. Big banks are unlikely to allow the release by the Bank of England of anonymized datasets based on their reported data that could then be used by others in lieu of their own data. Legislation, therefore, would probably be needed to allow the data to be used, but this would be a big political call and highly controversial. In any case, some in the industry are not comfortable with the concept of using external data of any kind, saying that goes against the spirit of the IRB methodology.

“The clue is in the name,” says one CEO. “It’s called ‘internal ratings based’ for a reason.”

Creating a new set of Basel-inspired standards that could be proportionately applied to firms below a certain size or scope would certainly be impossible before Brexit unless the EU adopted a very different approach to Basel implementation.

After Brexit, UK regulators could toy with this, but doing so would be fraught with potential accusations of the kind of light-touch regulation that the financial crisis was supposed to have consigned to history.

There is a case to be made that Basel standards were intended as a means of standardizing the regulatory approach for internationally active firms rather than for smaller institutions, but it seems unthinkable that the UK would attempt this route.

The most likely result is that regulation at the Basel level – with vigorous input from UK regulators – will inexorably lead to a gradual lessening of the capital disparity between the biggest banks and the smallest. But no single change will contribute more to this than any other. IRB standards as set down by Basel will get tougher, which could have the effect of lessening big banks’ capital advantages over smaller firms using the standardized approach, even with the latter also getting more stringent in certain areas.

At the same time, UK regulators will doubtless look to exercise Basel options to waive certain punitive risk weights wherever possible, as they currently do for buy-to-let. And they will certainly continue to work with firms to streamline the IRB transition process.

“This is where more could easily be done,” says one adviser. “It would help to be clearer around what ‘good’ looks like.” That, at least, looks set to be clarified soon.

The array of moving parts is formidable: Basel’s simultaneous move to tighten the standardized approach and IRB methodology; the PRA’s moves to strengthen oversight of certain segments like buy-to-let; continued lobbying by UK regulators at the Basel level to keep the concept of proportionality high on the agenda; and finally Brexit.

It is undeniable that challengers have seized on Brexit as one of their best hopes for change, particularly in the face of a Basel Committee that is inclined to get tougher, not more relaxed. The problem is that one part of the banking system cannot be evaluated in a vacuum. No one knows how discussions about the future access that big financial firms in the UK will have to European markets will play out, nor what compromises will need to be accepted in order for a solution to be found.

“After Brexit, theoretically the UK would be in the position of not having to comply with EU regulations, but pragmatically, given the position of the London financial sector, I think it would be very difficult for the UK to take a very different route to the Basel Committee,” says PwC’s Wong.

So while Brexit might offer a tantalizing glimpse of a future in which smaller firms are finally unshackled, the reality could be that UK regulators’ hands are merely tied in ways that are different to now but no less substantial. Ironically, Brexit itself could be the main reason why the UK would not contemplate going it alone on standards.

“Given everything that is going to have to happen, there are obvious benefits to the UK as a financial centre in being seen to stick to global standards as much as possible,” says another source. “If not, there is a danger that we would not be seen as equivalent.” If Brexit negotiations over passporting rights and access to the single market for financial services are as tough as they are expected to be, European leaders will need little invitation to deem the UK noncompliant with the stuff that matters. ‘Equivalence’ will almost certainly be a prerequisite.

“I don’t think much will change in the long run – I don’t see much appetite to create a more relaxed environment,” says Terrington at Paragon. It is hard to argue against this assessment. There is a political and regulatory will to be seen to be doing something – if for no other reason than to make the debate go away. But loosening capital requirements is not seen as a likely option.

“Politicians will always be nervous about banks manipulating capital rules, because banks have a habit of doing it, and when they do they tend to create problems,” says Shawbrook’s Pateman. He sees the adoption of a tougher Basel approach to IRB methodology as the more likely long-term outcome, with perhaps an increase in leverage ratios. The most egregious capital disparities will certainly lessen if the Basel IV amendments to the framework are imposed as currently proposed.

Any continued advantage that larger banks enjoy would be justified by their scale and sophistication and counterbalanced by the considerable costs stemming from tougher additional regulatory buffers, oversight and legacy costs. What is clear is that smaller firms looking for a future in which they can set up without such costs or buffers and simply snap up the capital arbitrage play are likely to be disappointed.

“The challenger bank community is going through its own challenges in terms of margins in this low-rate environment,” says PwC’s Wong. “It’s likely there will be some winners and some losers. In five years’ time there will probably have been consolidation of the current stock, but the sector is so dynamic that there will be new ones.”

Terrington has his own grim thought experiment to make the point.

“Imagine a future, in many years’ time, after another crisis,” he muses. “The PRA is sitting in front of another parliamentary committee, being asked: ‘So, how long had these banks been operating for when you decided to make it much easier for them?’”